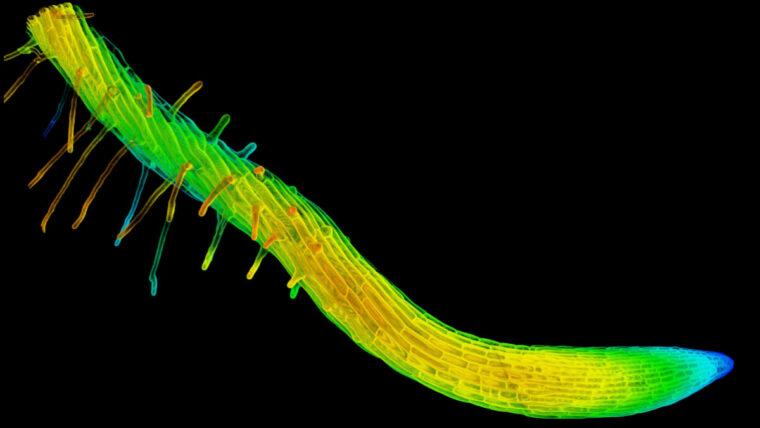

image description

From morning glories spiraling up fence posts to grape vines corkscrewing through arbors, twisted growth is a common phenomenon throughout the plant kingdom. This unique adaptation allows roots to maneuver around obstacles like rocks and debris. Scientists have long known that mutations in certain genes affecting microtubules can cause plants to grow in a twisting manner. In most cases, these are “null mutations,” meaning the twisting often results from the absence of a particular gene.

This curious phenomenon has puzzled plant scientists, including Ram Dixit, the George and Charmaine Mallinckrodt Professor of Biology at Washington University in St. Louis. The absence of a gene typically causes various problems for plants, yet twisted growth is a widespread evolutionary adaptation. Dixit, along with his former PhD student Natasha Nolan and the WashU McKelvey School of Engineering’s Guy Genin, has found a possible answer, now published in Nature Communications.

Unveiling the Mystery of Twisted Growth

The research reveals that a full null mutation is not necessary for the twist; rather, a change in gene expression in a specific location—the plant epidermis—is sufficient. “That might explain why this is so widespread: you don’t need null mutations for this growth habit, you just need ways to tweak certain genes in the epidermis alone,” Dixit explained. The study emerged from the National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center for Engineering Mechanobiology (CEMB), a nationwide consortium co-led by WashU that unites biologists, engineers, and physicists to understand how physical forces shape living systems.

“This discovery is a perfect example of what our center was designed to do,” said Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering and co-director of CEMB. “By combining biological experiments with mechanical modeling, we uncovered a fundamental principle: the outermost layer of the root dominates its twisting behavior through the same torsion physics (twisting from applied torque) that explains why hollow tubes can be almost as strong as solid rods. Geometry matters enormously.”

Implications for Agriculture and Ecosystems

Beyond being an evolutionary curiosity, understanding how roots navigate soil is increasingly urgent. As climate change intensifies droughts and pushes agriculture onto marginal lands with rocky, compacted soils, crops with root systems that can thrive in challenging conditions are becoming a critical need. “Roots are the hidden half of agriculture,” said Charles Anderson, a professor of biology and CEMB leader at Pennsylvania State University and a co-senior author on the paper.

“A plant’s ability to find water and nutrients depends entirely on how its roots explore the soil. If we can understand how roots twist and turn past obstacles, we could help crops survive in places they currently cannot.”

Twisted growth also plays roles in how vines climb, how stems resist wind, and how plants anchor themselves against erosion—factors critical for both food security and ecosystem resilience.

Solving the Riddle of Root Behavior

Using a model plant system where roots can skew right or left, Nolan investigated which plant cell layers regulate the twisting behavior. Plant cells are rigidly locked in place, almost glued together and surrounded by a tough cell wall. The team hypothesized that the twists emerge from the inner cortical layer where mutation causes the cells to be short and wide instead of long and skinny. The thinking was that the twisting phenotypes emerge because the epidermal layer must “lean over” to maintain its structural integrity and reach its squat cortical-layer neighbors.

Nolan, now at Pivot Bio, sought to restore straight roots by expressing the wild-type gene in a cell layer-specific manner instead of throughout the root as previously done. The striking finding was that expressing this wild-type gene in any of the inner cell layers did not change the twisty appearance. “It didn’t matter that you now had that protein being made in some of the inner cell layers, it was as if it didn’t exist,” Dixit said. In contrast, when the wild-type gene was expressed only in the epidermis, the roots went straight, indicating that “the dominating cell layer, that’s really dictating this behavior, is the epidermis,” Dixit noted.

The mystery solved, the epidermis is calling the shots on the twist. But how? That’s where mechanobiologists, including co-authors Genin and Anderson, came in. Anderson’s lab measured the orientation of the cellulose microfibrils in mutant and wild-type roots. The twisty defects seem to alter the cellulose deposition, and Genin developed a computer model explaining why the epidermis dominates.

“When you have concentric layers of cells, like rings in a tree trunk, the outer ring has far more leverage over the whole structure than the inner rings,” Genin explained. “Our model showed that if only the epidermis has skewed cell files, it can drive about one-third of the total twisting you’d see if every layer were skewed. But if you fix just the epidermis, the whole root straightens out. The math was unambiguous: the outer layer rules.”

The model confirmed what Nolan found in her experiments. When she expressed the wild-type (straight root) gene only in the epidermis, it affected even the cortical cells that still carried the mutation. Instead of being short and wide, those inner cells became longer and skinnier, almost like the wild type.

“Somehow the epidermal cell layer is able to entrain inner cell layers,” Dixit said. “The epidermis is not a passive skin, but instead a mechanical coordinator of the growth of the entire organ.”

Future Applications and Research Directions

Now that scientists understand how plants “do the twist,” they can apply these findings to address challenges in agricultural science. “Imagine being able to design plants that dial up or dial down a root’s tendency to twist,” Anderson said. “In rocky, inhospitable conditions, you might want roots that corkscrew past obstacles. This research gives us a target and a mechanical framework for thinking about root architecture as an engineering problem.”

Genin emphasized the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in solving such complex problems. “A biologist alone might have found that the epidermis matters, but wouldn’t have had the tools to explain why. An engineer alone couldn’t have done the genetics and phenotyping,” he said. “Together, as a center, we got the full picture.”

The research, titled “The epidermis coordinates multi-scale symmetry breaking in chiral root growth,” was published in Nature Communications and supported by the Center for Engineering Mechanobiology, a National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The work was also funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences.