People who suspect that their sense of smell has been dulled after a bout of COVID-19 are likely correct, according to a new study using an objective, 40-odor test. Even those who do not notice any olfactory issues may be impaired, the research suggests.

The study, led by the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER initiative and supported by its Clinical Science Core at NYU Langone Health, explored the link between the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 and hyposmia — the reduced ability to smell. The findings revealed that 80% of participants who reported a change in their smelling ability after having COVID-19 scored low on a clinical scent-detection test taken about two years later. Of this group, 23% were severely impaired or had entirely lost their sense of smell.

Notably, 66% of infected participants who did not notice any smelling issues also scored abnormally low on the evaluation, according to the study authors. “Our findings confirm that those with a history of COVID-19 may be especially at risk for a weakened sense of smell, an issue that is already underrecognized among the general population,” said study co-lead author Leora Horwitz, MD.

The Broader Implications of Hyposmia

Hyposmia has long been associated with weight loss, reduced quality of life, and depression, among other concerns. Those with a diminished sense of smell may also struggle to detect dangers such as spoiled food, gas leaks, and smoke. Furthermore, scientists have flagged smelling dysfunction as an early sign of certain neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, which can affect the brain’s scent-processing region.

While past research has identified hyposmia as a symptom of coronavirus infection, most studies have relied on patients’ own assessments of their smelling ability. Such subjective measures are not always reliable and cannot effectively track the problem’s severity and persistence, notes Horwitz.

Groundbreaking Research and Its Findings

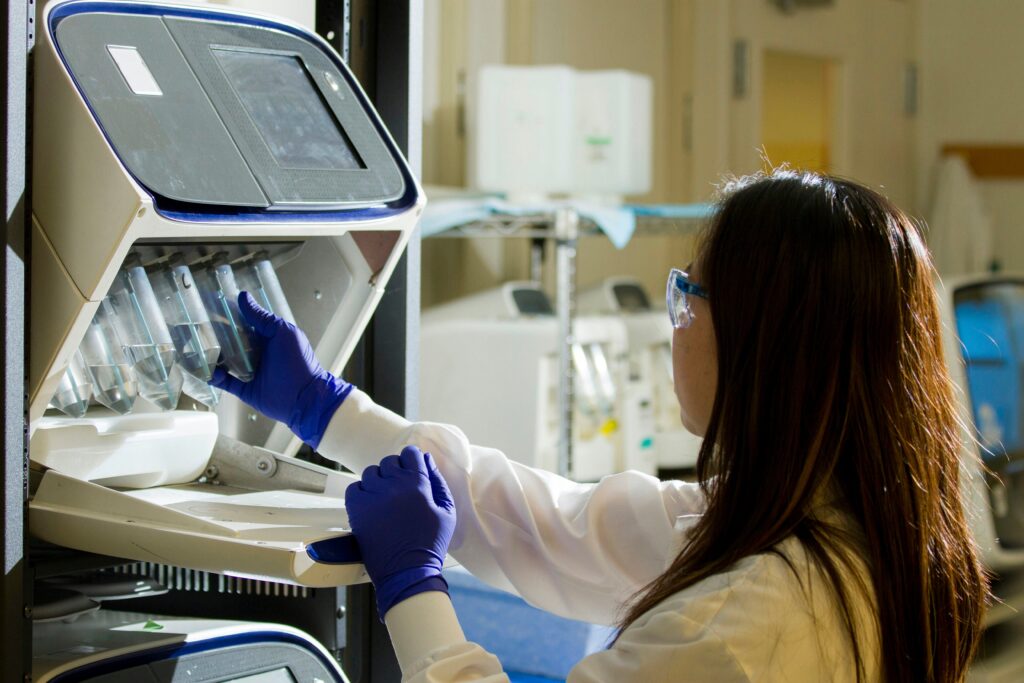

The new study, published online on September 25 in the journal JAMA Network Open, is the largest to date to examine loss of smell after COVID-19 using a formal test. The research involved 3,535 men and women, with the team assessing thousands of Americans who had participated in the RECOVER adult study, a multicenter analysis designed to shed light on the long-term health effects of the coronavirus.

To measure olfactory function, the team used the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT). This scratch-and-sniff evaluation, considered the gold standard of its kind, asked participants to identify 40 scents by selecting the correct multiple-choice option for each odor. A correct answer earned one point, and the total UPSIT score was compared with a database of thousands of healthy volunteers of the same sex and age. Based on the results, smelling ability was characterized as normal, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, severely impaired, or lost altogether.

“These results suggest that health care providers should consider testing for loss of smell as a routine part of post-COVID care,” said Horwitz. “While patients may not notice right away, a dulled nose can have a profound impact on their mental and physical well-being.”

Looking Ahead: Potential Treatments and Challenges

Experts are now exploring ways to restore smelling ability after having COVID-19, such as vitamin A supplementation and olfactory training to “rewire” the brain’s response to odors. A deeper understanding of how the coronavirus affects the brain’s sensory and cognitive systems may help refine these therapies, notes Horwitz.

However, Horwitz cautions that the study team did not directly assess loss of taste, which often accompanies problems with smell. Additionally, it is possible that some uninfected participants were misclassified due to the lack of universal testing for the virus. This may help explain the surprisingly high rate of hyposmia identified in those without a supposed history of COVID-19, she says.

The study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL162373, U01DC019579, OT2HL161847, OT2HL161841, and OT2HL156812. Other NYU Langone researchers involved in the study include Gabrielle Maranga, MPH, and Jennifer Frontera, MD, among a large team of collaborators from institutions across the United States.

As the world continues to grapple with the long-term impacts of COVID-19, studies like this one are crucial in understanding the full spectrum of the virus’s effects on human health. The findings underscore the importance of ongoing research and the need for healthcare systems to adapt to the evolving challenges posed by the pandemic.