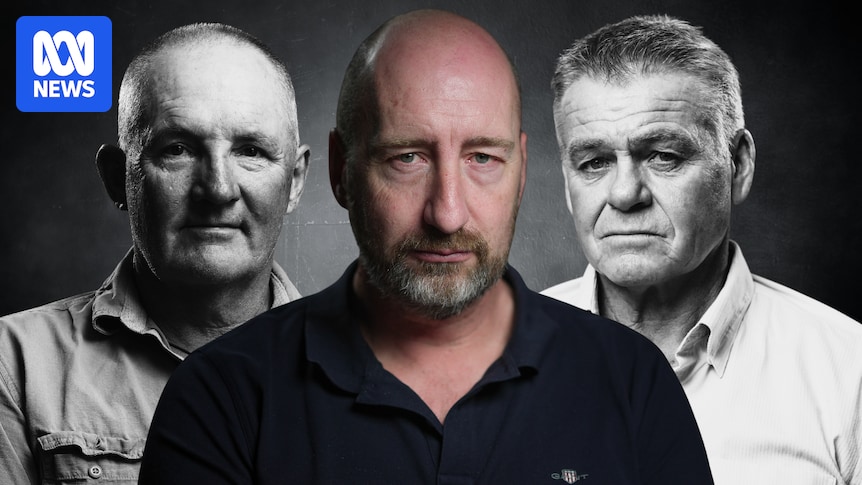

Military advocates are tasked with aiding vulnerable veterans, yet the system remains largely unregulated, leaving individuals like Peter Alchin and the married couple Brenton and Liane Lawrence exposed to fraudsters. This story, which includes distressing details of suicide, highlights the failures in vetting processes that allowed a convicted criminal to operate unchecked.

John Simmons, previously labeled a “fraudster, con-man, and a liar” by a judge, managed to deceive veterans despite his criminal history. After three years of struggling to access his veteran entitlements, former army apprentice Mr. Alchin sought Simmons’ help, initially believing he was making progress. For each successful compensation claim, Mr. Alchin paid Simmons $1,000. However, Simmons later convinced him to transfer $16,850 for a non-existent court case, promising over $1 million in compensation that never materialized.

Unveiling the Deception

When Mr. Alchin discovered the court case was fictitious, he was “gobsmacked.” CSC investigators confirmed there was no legal action on his behalf, and the barrister Simmons mentioned did not exist. Despite these revelations, Simmons maintained he had “done the work” without charging for it. However, 7.30, an investigative program, spoke to 14 veterans who all reported similar experiences with Simmons, who often blamed the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) for losing paperwork.

In a statement, DVA refuted claims of regularly misplacing veterans’ documentation. Yet, Simmons, authorized by DVA to advocate for veterans, had two prior fraud-related convictions. In 2015, he was convicted of deception and dishonesty, having falsified documents to sell a non-existent vehicle. Despite pleading guilty, Simmons insisted his intentions were altruistic, questioning why he wasn’t “living the high life” if he were a con-man.

The Jesse Bird Welfare Centre and Further Exploitation

In 2019, Simmons opened the Jesse Bird Welfare Centre in Adelaide, named after an Afghanistan veteran who took his own life. Brenton Lawrence, a former army avionics technician, and his wife Liane initially trusted Simmons, donating time and money to the center. They even offered to sell Simmons a property at half its value, believing he was genuinely assisting veterans. However, Simmons failed to pay the full deposit, offering excuses and fake bank references.

The Lawrences became suspicious when their compensation claims didn’t appear online, despite Simmons’ assurances of personally submitting them. His aggressive communications with DVA staff led to a charge of using a carriage service to menace, harass, or cause offense. Simmons, suspended from advocacy work, claims the charge is an attempt to silence him.

Systemic Failures and Calls for Reform

The unregulated nature of military advocacy has led to a Senate inquiry, with submissions highlighting deceptive practices and exploitation. Lawyer Greg Isolani, with over three decades of experience, described the claims process as more complex than the tax system, stressing the high responsibility involved due to the vulnerability of veterans.

“It’s been described as ethereal,” Mr. Isolani told 7.30. “You’re talking about a vulnerable cohort, so it’s a high level of responsibility.”

Despite a national training program, there are no mandatory qualifications or criminal history checks for advocates. DVA plans to establish a professional institute to accredit and register advocates, aiming to enforce a code of conduct.

Lessons Learned and the Path Forward

For Mr. Alchin and the Lawrences, the lack of a protective framework was evident only after they discovered Simmons’ criminal past. Mr. Alchin, who also hired Simmons for car repairs, found his vehicles unroadworthy, with some disappearing altogether. When confronted, Simmons provided fake supplier lists and threatened legal action, which he later admitted was false.

Their chance encounter led to the unraveling of Simmons’ deceit. Mr. Lawrence, upon learning of Simmons’ past, received bizarre claims from Simmons about being targeted by “rebel bikies” and police brutality. The victims now demand change, questioning how someone with a criminal conviction could advocate for vulnerable veterans.

“How can a man with a criminal conviction be allowed to operate and function as an advocate for DVA with military personnel who are mentally vulnerable?” Mr. Alchin asked.

DVA asserts it is addressing advocacy issues through integrity measures and professional training. The unfolding inquiry and proposed reforms may pave the way for a more secure system, protecting veterans from exploitation and ensuring they receive the support they deserve.