In the bustling neighborhoods of Jamestown and Usshertown in Accra, Ghana, a recent study has shed light on the intricate relationship between the built environment, community stress, and the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). This research, conducted through a blend of qualitative focus group discussions and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping, offers a nuanced understanding of how local environments influence health outcomes.

The study, part of a larger effort to contextualize diabetes risk factors in Accra, employed Cognitive Mapping Focus Group Discussions (CM-FGDs) to explore community members’ perceptions of their environment. These discussions revealed that the local construction of the environment is deeply rooted in historical, social, and cultural experiences. Participants were encouraged to express their perspectives through drawings, which were later analyzed alongside GIS data to provide spatial context to the narratives.

Exploring the Built Environment

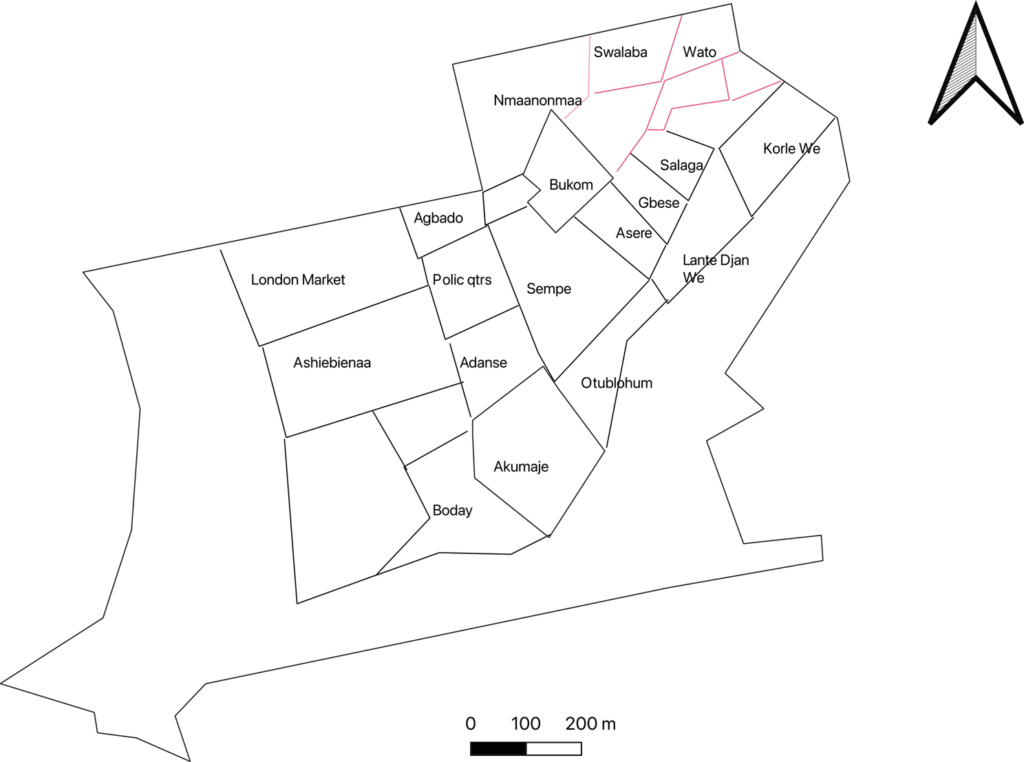

Jamestown and Usshertown, known collectively as Ga Mashie, are densely populated communities with over 120,000 residents in a one-square-mile area. The study’s setting is characterized by low educational attainment, high fertility rates, and a predominance of fishing and petty trade as occupations. These factors contribute to a unique social fabric that influences community health.

Participants in the study described their environment using five key elements: paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks. These elements, pioneered by urban planner Kevin Lynch, help construct a local perspective of the environment. For instance, paths include walkways and streets, while edges refer to boundaries. Districts are areas with specific features, nodes are junctions, and landmarks are major known features. These elements were crucial in understanding how community members perceive their surroundings.

Community Stressors and Health Risks

The study highlighted several environmental stressors, including hazardous heat and noise, which were frequently mentioned by participants. Overcrowding, domestic cooking, and industrial activities contribute to intense heat, leading to health issues such as sleeplessness and skin rashes. Noise pollution, stemming from religious activities, social events, and vehicular traffic, was identified as a significant stressor, linked to headaches and increased blood pressure.

“As for the churches, I wouldn’t want to mention them because they will say I don’t like God. Regarding the churches, all-night programmes used to be only Fridays but now they do it Wednesdays and Fridays. So just imagine if you live closer to a church. We are becoming used to it because we have lived with it for quite some time.” – Man from Usshertown, FGD 6

The Role of the Food Environment

Food culture in Ga Mashie plays a significant role in community health. The study found that street food vendors dominate the food environment, selling meals rich in artificial seasonings and flavors. Participants noted a shift towards “tasty food” that is associated with lifestyle diseases like diabetes. The high population density and lack of cooking units in homes further drive reliance on out-of-home meals.

“Maggi, A1 and different spices. They use it to prepare the food just to make it taste good, but it is not good for our health.” – Food vendor from Jamestown, FGD 8

Late-night meals, a common practice in the vibrant nightlife of the communities, were also identified as a risk factor for diabetes. Participants expressed concerns about the health implications of consuming food late at night, linking it to heartburn and elevated sugar levels.

Physical Activity and Lifestyle Choices

Opportunities for physical activity in Ga Mashie are limited, with parks and fitness centers primarily serving younger males. The lack of accessible spaces for women and older adults contributes to low physical activity levels. This, combined with dietary practices, underscores the community’s vulnerability to diabetes and CVDs.

“Yes. At the roundabout there is space. They call the place Buduemu. You can exercise there but you need to pay for the place before you get to [exercise]. But at the roundabout, you will see only boys.” – Woman from Usshertown, FGD1

Community Perspectives and Future Directions

The study’s findings highlight the complex interplay between the built environment and health risks in urban Accra. Community members expressed a sense of powerlessness over environmental stressors such as heat and noise, which are beyond their control. However, the study also points to potential community-level strategies that could mitigate these risks.

For instance, the annual ban on drumming and noise-making preceding the community festival demonstrates the potential for collective action. Engaging active community organizations, such as market women’s groups and youth groups, could advocate for reforms through traditional councils and local government bodies.

While the study’s insights are specific to Jamestown and Usshertown, they offer valuable lessons for similar urban poor contexts in Ghana and beyond. By understanding community perspectives and leveraging local strengths, meaningful solutions can be developed to address the health challenges posed by the built environment.

As urbanization continues to shape the landscapes of cities like Accra, the need for inclusive and sustainable urban planning becomes increasingly critical. This study underscores the importance of integrating community voices into the conversation, ensuring that interventions are grounded in local realities and cultural contexts.