China has recently made headlines with the commercial operation of a supercritical carbon dioxide power generator, hailed as a technological breakthrough. Known as Chaotan One, this system is installed at a steel plant in Guizhou province, southwest China, and is designed to convert industrial waste heat into electricity. Each unit is rated at approximately 15 MW, with configurations totaling around 30 MW. Public statements boast efficiency improvements of 20% to over 30% compared to conventional steam-based systems. These impressive figures have garnered significant attention.

However, China’s history of firsts in technology does not always guarantee long-term success or widespread adoption. The nation has the capacity to experiment with novel systems, learning from both successes and failures. This approach, often described as “crossing the river by feeling for stones,” allows for valuable insights but also results in many dead ends. The real question is whether the supercritical CO₂ technology will withstand practical operating conditions to justify broader deployment.

China’s Experimental Approach

China’s strategy of deploying first-of-a-kind systems is not new. The country has the financial and regulatory means to scale successful technologies rapidly. Yet, the limited deployment of certain technologies, such as small modular reactors and experimental molten salt reactors, suggests economic and practical challenges. Despite having the resources to expand these technologies, China has not done so, indicating potential limitations.

Similarly, China’s initial enthusiasm for hydrogen transportation has waned as battery electric vehicles have gained commercial traction. This pattern highlights China’s tendency to scale technologies that prove commercially viable, while others remain as small-scale experiments.

The Supercritical CO₂ Technology

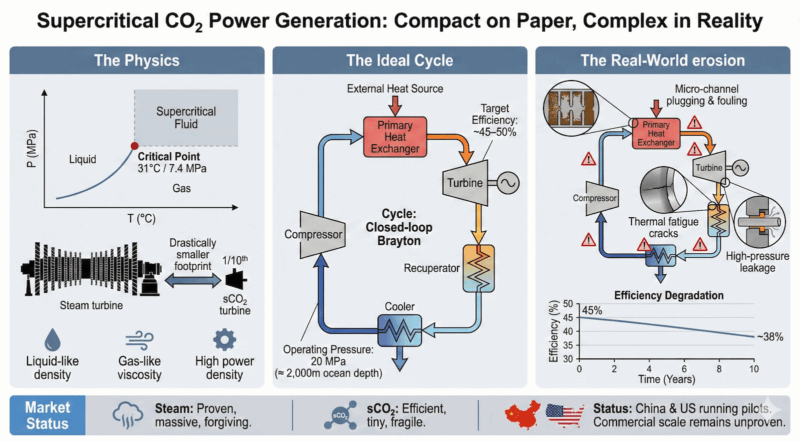

Supercritical CO₂ power systems represent a form of thermal generation, converting heat into mechanical work to drive an electrical generator. This concept is similar to traditional power plants but differs in the working fluid and thermodynamic cycle. Carbon dioxide becomes supercritical above 31°C and 73 atmospheres of pressure, exhibiting properties between a gas and a liquid. This state allows for smaller turbomachinery and compact systems, often touted as advantages of the technology.

The thermodynamic cycle typically used is a Brayton cycle, which compresses a fluid, heats it, expands it through a turbine, and then cools it. Supercritical CO₂ offers favorable properties on paper, but these same properties make the system sensitive to deviations and contamination.

Challenges and Skepticism

The Chinese installation operates as an indirect heated closed-loop system, transferring heat from the steel plant into the CO₂ loop. It operates at high pressures and temperatures, claiming efficiency improvements over steam-based systems. However, the lack of detailed information on materials, operating margins, and maintenance raises questions about long-term durability.

The United States, on the other hand, has taken a cautious approach with its DOE-backed Supercritical Transformational Electric Power (STEP) facility in Texas. This installation focuses on component validation and risk reduction rather than commercial operation, accompanied by extensive laboratory research on materials and durability.

“Supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycles have been attempted since 1946 without success.”

This historical context underscores the recurring challenges of materials and durability in supercritical CO₂ systems. The technology’s potential has been explored for decades, but practical obstacles have persisted.

Material and Technical Hurdles

Key challenges include maintaining heat exchanger performance, seal integrity, and managing impurity-driven corrosion. Supercritical CO₂ systems rely on printed circuit heat exchangers with small channels, which must withstand high pressures and temperatures. These exchangers are costly and difficult to repair, making their longevity critical to system economics.

Seal degradation, similar to challenges faced in hydrogen systems, can lead to efficiency losses over time. Impurity-driven corrosion poses additional risks, particularly in industrial environments where contaminants are common.

Future Prospects and Conclusion

While the Chinese and U.S. efforts in supercritical CO₂ technology are noteworthy, early efficiency claims should be viewed with caution. The potential for degradation and maintenance challenges could undermine the technology’s long-term viability. The probability of efficiency losses from various mechanisms is significant, suggesting that supercritical CO₂ systems may not become a major player in electricity generation.

Ultimately, supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycles may find niche applications in specialized environments, but they are unlikely to replace conventional thermal systems on a large scale. If both the Chinese and U.S. installations maintain performance without significant issues over several years, it may warrant a reassessment. Until then, the technology remains an intriguing experiment rather than a transformative solution.