The advent of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) and its capacity to produce fake data, images, and text presents an unprecedented challenge to the integrity of scientific literature. Open Science, with its emphasis on data transparency, acts as a crucial safeguard against such fraudulent activities, providing an auditable trail of evidence. However, this very openness also fuels GenAI engines, creating a paradox in the fight against AI-generated fraud.

Robust evidence suggests that open access datasets, especially in health and medicine, are being exploited by paper mills and other bad actors. This exploitation results in high volumes of low-value or misleading research, leading to undesirable consequences such as misallocation of funding, distortion of assessment metrics, and reduced trust in scientific literature.

The Double-Edged Sword of Open Access

Open Science offers numerous benefits, including equitable data access and improved reproducibility of research. However, the open availability of datasets also poses risks. Datasets are the fuel for AI engines, and open access can inadvertently support GenAI-assisted fast churn science. This issue is particularly pronounced in the realm of health and medicine, where data exploitation is rampant.

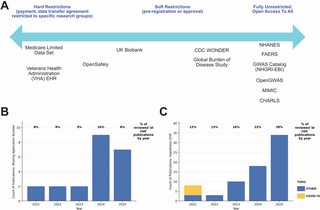

Both publishers and the scientific community are taking action against fake or duplicated images and the use of tortured phrases to avoid plagiarism checks. Yet, this is an adversarial process, and problematic research continues to be published. While some datasets operate under controlled access, others, like the Centre for Disease Control’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), remain fully open and AI-ready, making them susceptible to exploitation.

Balancing Open and Controlled Access

There is a growing argument that unfettered open access is undesirable, leading to unwanted behaviors such as p-hacking, hypothesizing after results are known (HARKing), and the introduction of false discoveries. Conversely, heavily restricted systems are inequitable and risk monopolization by users with specific research objectives or biases.

Some resources have adopted a middle path. The UK Biobank, for example, provides access to de-identified data for all eligible researchers globally, provided the research is health-related and in the public interest. This access is managed through a system that includes ethical reviews and legal agreements, ensuring alignment with its public interest mandate.

Case Study: UK Biobank

The UK Biobank’s Access Management System and application-specific registration IDs serve as a form of pre-registration, protecting against practices like ‘salami slicing’ and HARKing. However, a pilot audit of 321 research papers using UK Biobank data found that 7% did not report a valid application number, and 25% exhibited substantial hypothesis drift. This drift increased annually, highlighting potential weaknesses in the system.

“The proportion of publications without an application number varied by year but did not show any clear trend, but the proportion showing hypothesis drift increased each year, from 12% in 2021 to 28% in 2025.”

While these findings are based on a purposive sample, they underscore the vulnerability of open-access data sources. The UK Biobank is used here as a case study, but the issue is pervasive across all open-access data sources.

Implications and Future Directions

Open-access data sources are public goods, yet they are susceptible to exploitation by unethical actors. Proponents of open and equitable access argue based on strong ethical grounds, emphasizing the importance of reproducibility in experimental research. However, once a dataset’s credibility is compromised, it becomes more challenging for researchers to publish their findings.

The NHANES dataset illustrates this challenge, with some publishers no longer accepting submissions based on open-access public health datasets. This highlights the real cost of not exerting preventive control over data usage.

Moving forward, a balanced approach to data access is essential. Controlled access systems, like that of the UK Biobank, offer a model for maintaining data integrity while ensuring equitable access. However, these systems require robust enforcement and transparency to be effective.

As the scientific community continues to grapple with the challenges posed by GenAI, it is crucial to develop strategies that safeguard the integrity of scientific research while promoting open access and reproducibility. This delicate balance will be key to advancing knowledge in an era increasingly dominated by artificial intelligence.