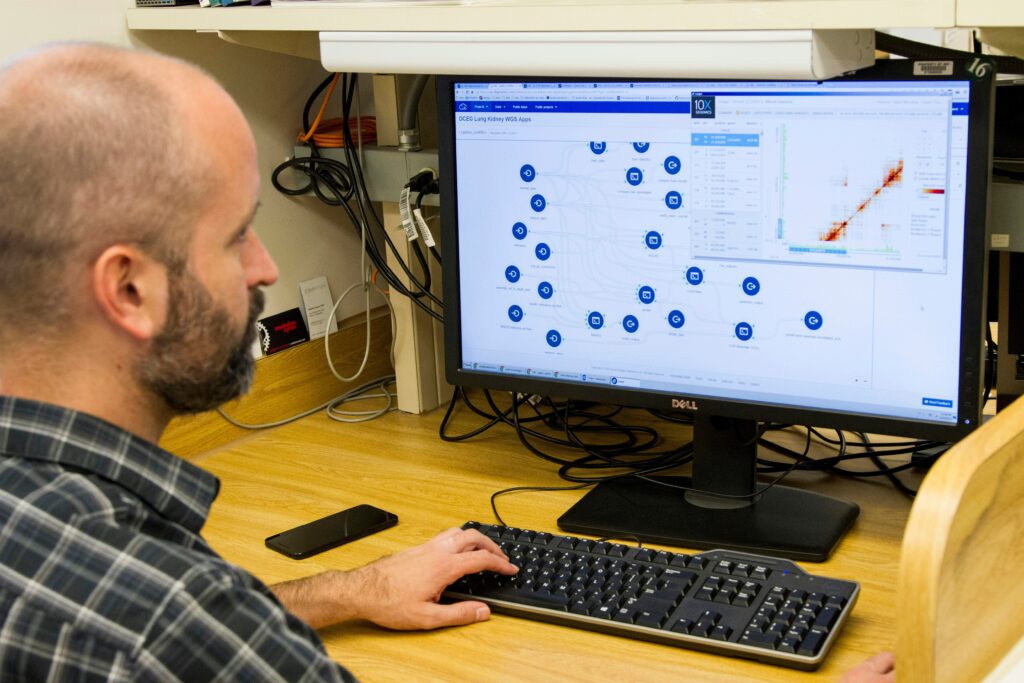

Data passively collected from cellphone sensors may soon revolutionize mental health care, identifying behaviors linked to a range of disorders such as agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. Recent findings suggest that this data can also pinpoint behaviors associated with a broader spectrum of mental health symptoms, offering new possibilities for diagnosis and treatment.

Colin E. Vize, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh’s Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, co-leads this groundbreaking research. The study expands the potential for clinicians to use sensor data in treating patients. Whitney Ringwald, a professor at the University of Minnesota and a graduate of Pitt, spearheaded the study, alongside former Pitt Professor Aiden Wright and his graduate student, Grant King.

Potential Clinical Applications

“This is an important step in the right direction,” Vize remarked, “but there is a lot of work to be done before we can potentially realize any of the clinical promises of using sensors on smartphones to help inform assessment and treatment.”

In theory, an app utilizing such data could provide clinicians with more reliable insights into patients’ lives between visits. “We’re not always the best reporters; we often forget things,” Vize noted regarding self-assessments. “But with passive sensing, we might be able to collect data unobtrusively, as people go about their daily lives, without having to ask a lot of questions.”

Research Methodology and Findings

As a preliminary step, researchers examined whether cellphone sensor data could infer behaviors associated with specific mental health conditions. Previous studies have linked sensor readings to illnesses like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. This new research, published in the journal JAMA Network Open on July 3, extends those findings, demonstrating connections to symptoms not confined to a single disorder.

“The disorder categories tend to not carve nature at its joints,” Vize explained. “We can think more transdiagnostically, and that gives us a little more accurate picture of some of the symptoms that people are experiencing.”

Understanding the P-Factor

The study utilized a statistical analysis tool called Mplus to correlate sensor data with mental health symptoms reported at baseline. Researchers sought to determine if sensor data corresponded with six broad symptom dimensions: internalizing, detachment, disinhibition, antagonism, thought disorder, and somatoform symptoms. Additionally, they explored the p-factor, a shared feature across various mental health symptoms.

“You can think about it sort of like a Venn diagram,” Vize said. If all symptoms associated with mental health issues were circles, the p-factor is the space where they all overlap. It is not a behavior in and of itself. “It’s essentially what’s shared across all dimensions.”

The research team analyzed data from the Intensive Longitudinal Investigation of Alternative Diagnostic Dimensions study (ILIADD), conducted in Pittsburgh in spring 2023. They reviewed data from 557 participants who completed self-assessments and shared cellphone data, including GPS location, physical activity, screen time, call logs, battery status, and sleep patterns.

Implications and Future Directions

Using an app developed by the University of Oregon researchers, the team linked sensor data to various mental health symptoms. The findings showed that the six dimensions of mental health symptoms correlated with the sensor data, as did the p-factor, a general marker of mental health issues.

The implications of these findings are significant. In the future, this technology could enhance understanding of symptoms in patients whose presentations do not fit neatly into a single disorder category. However, the data currently reflects averages and does not provide individual diagnoses. “These sensor analyses may more accurately describe some people than others,” Vize cautioned.

Despite the promising potential, Vize emphasized that this technology is unlikely to replace human clinicians. “A lot of work in this area is focused on getting to the point where we can talk about, ‘How does this potentially enhance or supplement existing clinical care?’ Because I definitely don’t think it can replace treatment. It would be more of an additional tool in the clinician’s toolbox.”

As research continues, the integration of passive sensor data into mental health care could offer a valuable supplement to traditional diagnostic and treatment methods, providing clinicians with a more comprehensive view of their patients’ mental health.