Scientists have made a significant leap toward constructing the world’s first practical nuclear clock. In a groundbreaking study published today in Nature, researchers unveiled a novel method of probing the precise “ticking” of the thorium-229 nucleus without the need for specialized transparent crystals. This advancement could pave the way for a new class of highly accurate timekeeping devices, potentially transforming fields such as navigation, communications, earthquake and volcano prediction, and deep-space exploration.

The development builds on a pivotal achievement from last year, where the team successfully used a laser to excite the nucleus of thorium-229 within a transparent crystal—a milestone that had been the focus of their research for the past 15 years. Now, the researchers have replicated these results using a minuscule amount of material with a method that is both simple and cost-effective, opening the door to practical nuclear clock technology.

Revolutionizing Timekeeping

Dr. Harry Morgan, co-author of the research and Lecturer in Computational and Theoretical Chemistry at The University of Manchester, explained, “Previously, the transparent crystals needed to hold thorium-229 were technically demanding and costly to produce, which placed real limits on any practical application. This new approach is a major step forward for the future of nuclear clocks and leaves little doubt that such a device is feasible and potentially much closer than anyone expected.”

In the new study, the team excited the thorium nucleus within a microscopic thin film of thorium oxide, created by electroplating a minute amount of thorium onto a stainless-steel disc—a process akin to gold-plating jewelry. This represents a radical simplification of their previous method.

Technical Breakthroughs

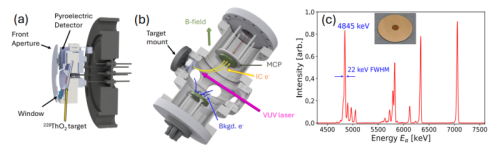

The thorium nuclei absorb energy from a laser and then transfer that energy to nearby electrons, which can be measured as an electric current. This method, known as conversion electron Mössbauer spectroscopy, has been used for years but typically requires high-energy gamma rays at specialized facilities. This study marks the first time it has been demonstrated with a laser in a standard laboratory setting.

Crucially, this research shows that thorium-229 can be studied within far more common materials than previously thought, eliminating one of the biggest obstacles to building practical nuclear clocks. The technique also provides new insights into the behavior and decay of thorium-229, which could inform future nuclear materials and energy research.

“We had always assumed that in order to excite and then observe the nuclear transition, the thorium needed to be embedded in a material that was transparent to the light used to excite the nucleus. In this work, we realized that is simply not true,” said UCLA physicist Eric Hudson, who led the research.

Potential Applications and Implications

Nuclear clocks, like atomic clocks, rely on the natural “ticking” of single atoms. However, while atomic clocks involve electrons, nuclear clocks use oscillations within the nucleus itself, making them far less sensitive to external disturbances and potentially orders of magnitude more accurate.

These clocks could even be used to predict earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. According to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, nuclear clocks should be sensitive to small changes in the Earth’s gravity caused by the movement of magma and rock deep underground. By deploying nuclear clocks in earthquake-prone regions such as Japan, Indonesia, or Pakistan, scientists could monitor subterranean activity in real-time and predict tectonic events before they occur.

Dr. Morgan added, “In the long term, this technology could revolutionize our ability to prepare for natural disasters. It’s incredibly exciting to think that thorium clocks can do things we previously thought were impossible, as well as improving everything we currently use atomic clocks for.”

Looking Ahead

This research, funded by the National Science Foundation, included contributions from physicists at the University of Nevada Reno, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Ziegler Analytics, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität at Mainz, and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. The study, published in the journal Nature, is titled “Laser-based conversion electron Mössbauer spectroscopy of 229ThO2” and can be accessed with DOI:10.1038/s41586-025-09776-4.

The implications of this breakthrough are vast, with the potential to impact various scientific and technological fields profoundly. As researchers continue to refine and develop this technology, the dream of a practical nuclear clock moves ever closer to reality, promising a new era of precision in timekeeping and beyond.