Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have unveiled a groundbreaking technique that allows for precise control over the internal structure of common plastics during 3D printing. This innovation, which was detailed in a paper published today in Science, enables a single printed object to transition seamlessly from rigid to flexible using only light.

The technique, known as crystallinity regulation in additive fabrication of thermoplastics (CRAFT), offers microscopic control over how plastic molecules arrange themselves as an object is printed. This development, according to the researchers, opens new possibilities in advanced manufacturing, soft robotics, national defense, energy damping, and information storage. The collaborative effort includes experts from Sandia National Laboratories, the University of Texas at Austin, Oregon State University, Arizona State University, and Savannah River National Laboratory.

Revolutionizing Material Properties with Light

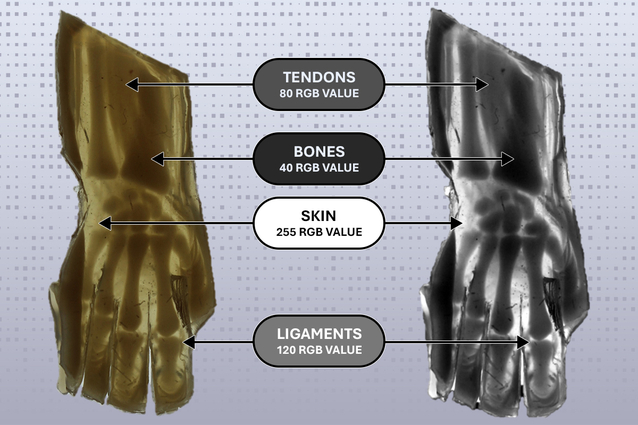

The research team demonstrated that by adjusting light intensity during the printing process, they could control how crystalline or amorphous a thermoplastic becomes at specific locations within a part. This molecular arrangement dictates whether a material behaves more stiffly and rigidly or as a softer, more flexible plastic, without altering the base material. CRAFT allows for spatial control of crystallinity during printing, rather than a uniform distribution throughout a part.

“A classic example of crystallinity is the difference between high-density polyethylene – picture a milk jug – and low-density polyethylene, like squeeze bottles and plastic bags,” said LLNL staff scientist Johanna Schwartz. “Our CRAFT effort is exciting in that we are controlling the crystallinity within a thermoplastic spatially with variations in light intensity, making areas of increased and decreased crystallinity to produce parts with control over material properties throughout the whole geometry.”

From Concept to Practical Application

Translating this new capability into practical manufacturing instructions posed a significant challenge, according to LLNL engineer Hernán Villanueva. He joined the project after early discussions with Schwartz and Sandia scientists Samuel Leguizamon and Alex Commisso identified a missing link: a method to convert any three-dimensional computer-aided design (CAD) into the detailed light patterns needed for the CRAFT method.

Villanueva leveraged his experience with a multi-institutional team focused on lattice structures and advanced manufacturing workflows. He developed software that rapidly converted complex, topology-optimized designs into printing instructions by parallelizing the process on LLNL’s high-performance computing (HPC) systems, reducing turnaround times from days to hours or minutes.

Applying this computational approach to CRAFT, Villanueva adapted the workflow to encode “changes in light” rather than material changes. This advancement allowed him to convert 3D CAD geometries directly into CRAFT printing instructions, cutting instruction-generation time from hours or even a full day to seconds, enabling rapid design iteration and demonstration of the method.

“This work is a natural extension of the Lab’s strengths in advanced manufacturing and materials by design,” Villanueva said. “As part of the CRAFT effort, we have evolved a tool that connects materials science with computational workflows and advanced printing, enabling us to move directly from a 3D design to a part with spatially varying properties.”

Implications for the Future of Manufacturing

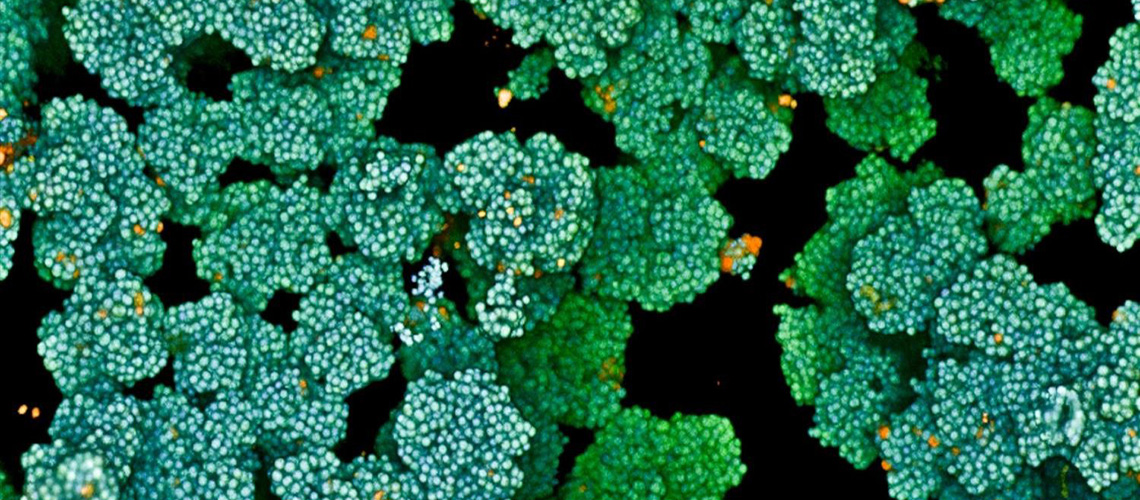

The CRAFT method relies on a light-activated polymerization process where exposure levels govern the stereochemistry of growing polymer chains. Lower light intensities favor more ordered crystalline regions, while higher intensities suppress crystallization, yielding softer, more transparent material. By projecting grayscale patterns during printing, the team produced parts with smoothly varying mechanical and optical properties.

The ability to tune properties by changing light intensity rather than swapping materials could significantly simplify additive manufacturing, Schwartz explained. “If you can get many different properties from one vat of material, printing complex multi-material or multi-modulus structures becomes much easier,” she said.

The researchers demonstrated the CRAFT technique on commercial 3D printers, fabricating objects that combine multiple mechanical behaviors in a single print. Examples included bio-inspired structures that mimic bones, tendons, and soft tissue, reproductions of famous paintings, and materials designed to absorb or redirect vibrational energy without adding weight or complexity. Among the most striking demonstrations was the ability to encode crystallinity through transparency differences.

“Being able to visualize the differences easily spatially, to the point of generating the Mona Lisa out of only one material, was incredibly cool,” Schwartz said.

Looking Forward: Sustainability and Broader Applications

LLNL’s Villanueva noted that the work reflects the Lab’s long-standing investments in HPC and in integrating modeling, design tools, and novel manufacturing processes. Future work could integrate topology optimization directly into the CRAFT framework, enabling researchers to optimize light patterns themselves to achieve desired performance.

Because the process works with thermoplastics—materials that can be melted and reshaped—printed parts remain recyclable and reprocessable, an important advantage for manufacturing sustainability. The findings suggest a future where 3D-printed plastic components can be tailored at the molecular level for specific functions, bridging the gap between material science and digital manufacturing.

From an applications standpoint, Schwartz highlighted the technology’s broad and near-term impact. “Energy dampening and metamaterial design are the most exciting use cases to me,” she said. “From space to fusion to electronics, there are so many industries that rely on energy and vibrational dampening control. This CRAFT printing process can access all of them.”