If an artist took a paintbrush, dipped it in white, and painted the Earth’s atmosphere from space, the result might resemble the stratocumulus cloud deck over the Pacific Ocean captured in photographer Michael Light’s archival project of the Apollo lunar missions. This striking image is part of the latest exhibition at the William Benton Museum of Art, where the intersection of art and science takes center stage.

To George Matheou, an associate professor in the School of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Manufacturing Engineering, the photo of the cloud deck appears almost like the stroke of a paintbrush. “Stratocumulus are thin sheets of clouds that form close to the Earth’s surface,” Matheou explains. “When you get a lot of them, they cool the planet very effectively. Because the clouds are white and bright, they reflect much of the solar radiation out to space and keep it from warming the ocean. It’s like painting the surface of the Earth with a reflective coating.”

The Scientific Importance of Clouds

As far as global warming is concerned, scientists, including Matheou, emphasize the importance of stratocumulus clouds. “But as the atmosphere and ocean warm, those clouds are becoming fewer, and that tends to make the situation even worse, because as you warm, you remove natural cooling at the same time, which accelerates the warming,” he says.

Matheou’s interest in clouds extends beyond their aesthetic appeal. As the head of UConn’s Computational Fluid Dynamics Group, he is keenly aware of the scientific challenges posed by cloud formations. “Clouds are the system that supports life on the planet, yet they’re the largest uncertainty in climate projections,” he notes. “Small changes in the Earth’s cloudiness can affect global temperature by a lot. Our goal is to understand how cloud systems work, especially as the climate warms and the clouds change.”

Art Meets Science at the Benton

For the culmination of his NSF award, Matheou collaborated with Benton Executive Director Nancy Stula to create an exhibition that blends art and science for a general audience. Stula curated the exhibition with a focus on photographs rather than paintings to depict clouds in the most scientifically accurate way possible.

Visitors to the exhibition are greeted by striking pieces such as photographer Kate Cordsen’s “Indigo” and Ansel Adams’ “White Branches, Mono Lake, Cloud Reflections, CA.” A nearby placard, written by Matheou, explains the relevance of fluid dynamics: “Fluid dynamics is concerned with how everything that flows, flows. Scientists and engineers study fluid motions to understand and predict biological and natural systems.”

Understanding Fluid Dynamics

Matheou explains the connection between fluid dynamics and clouds with an example: “Have you ever seen a plane leaving a white line behind it? That’s a manmade cloud called a concentration trail, or contrail. The jet engine burns fuel, which creates water vapor that goes into the atmosphere. If the humidity is high enough, the water vapor condenses and becomes either liquid or solid. A contrail is vapor that has become little ice crystals.”

He continues, “Fluids are gases and liquids, like the contrail. Mathematically, there’s a set of equations that describe how fluids move. If you solve the equations, you figure out what’s going to happen. But you cannot solve these equations by hand. You need a computer to do that, and we have a specialized computer, probably the size of this art gallery, to help us solve these equations.”

The Artistic Perspective

Matheou stands in the Benton gallery, admiring six photographs from artist Helen Glazer. “This is a cumulus cloud, or the remnant of one. Those are the small, puffy clouds that develop near the ground. It’s a liquid cloud, so the white you see are liquid droplets, like in the winter when you breathe out and you can see white. It’s the same kind of liquid droplets,” he says, pointing at one image.

Stula redirects him to a Sebastião Salgado piece that resembles a gigantic mushroom sprouting toward the heavens. “It’s one of the big thunderstorms you get in the tropics,” Matheou says. “The cloud is condensing water from the very bottom to the top, up 10 miles into the atmosphere. The more the water goes up, the cloud fills and becomes ice crystals. When they become big, they fall faster out of the cloud.”

This scientific narrative extends to “Hurricane Gladys Over the Gulf of Mexico #16” from Light’s Apollo project, which depicts the spiral of hurricane clouds in 1968. “These are basically big thunderstorms, organized together,” Matheou explains. “They grow tall and hit what we call the tropopause, which is the topmost part of the atmosphere called the troposphere where all the weather is confined. Above the tropopause, the atmosphere is much warmer, so weather can’t go in it. When the thunderstorms near the center of the hurricane hit the tropopause, the clouds spread horizontally, and that’s why this middle part looks like a cloudy disk.”

Science Can Be Beautiful, Too

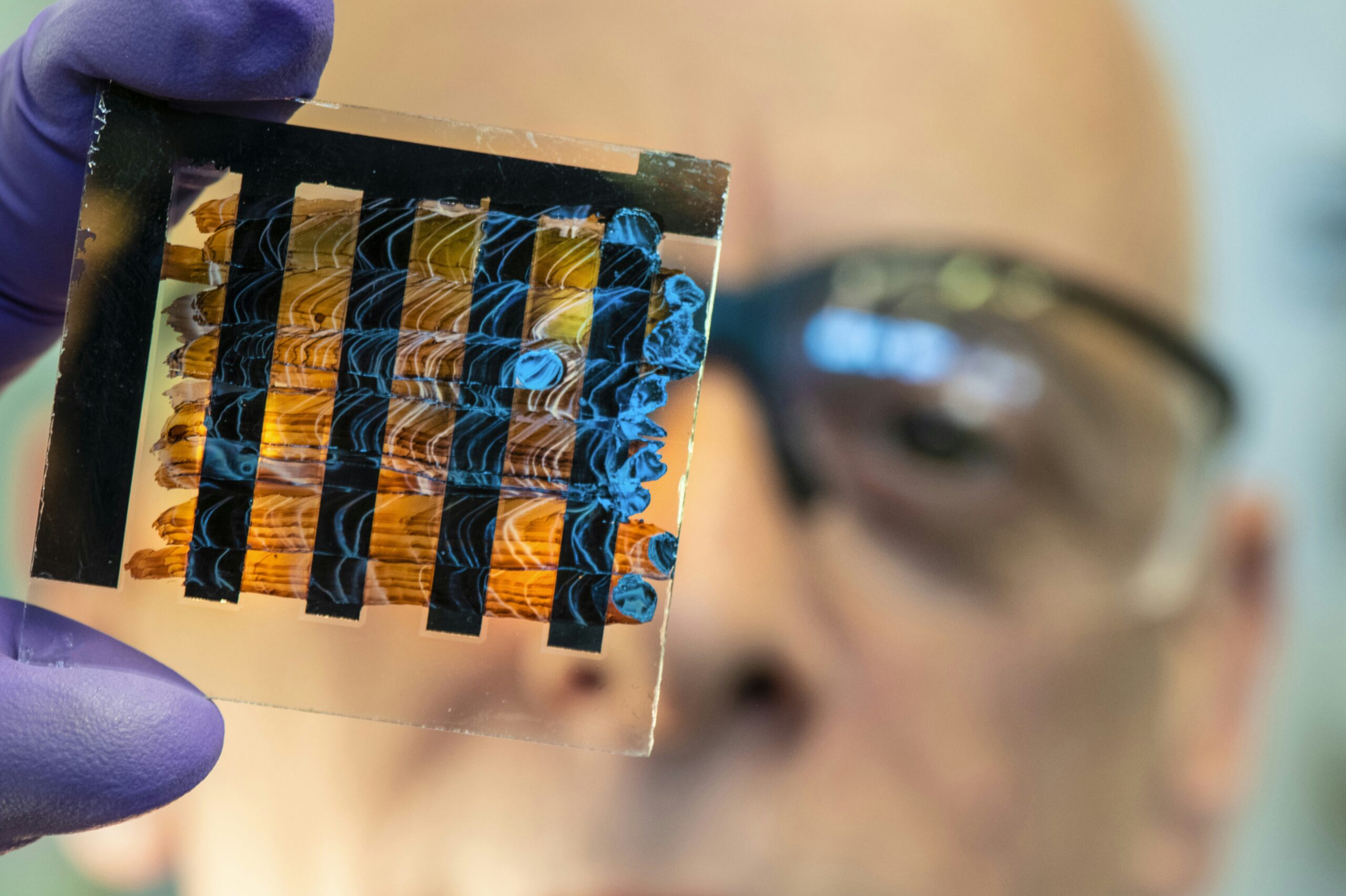

Matheou never imagined he’d be among the artists on display. His “Large-eddy simulation of cumulus clouds” video shows on a loop in a small room off the main exhibition space, giving viewers the sensation of flying through the clouds. “It took a lot of computing to create this,” he says. “These are the actual simulations we do for our research. All of these are simulated on the computer by solving a complex set of equations run through the very big computer we have here on campus. It’s a scientific model that computes radiation in the atmosphere. We just used it in a creative way.”

Matheou stresses that the video isn’t like the graphics one would see in a video game or movie, as those aren’t necessarily faithful to science. His video shows the exact formations that cloud deck would take in nature over about 45 minutes, through the clouds’ birth, development, active phase, and dissipation. It’s a project that earned him the American Physical Society’s Gallery of Fluid Motion contest in November 2021 and later exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C.

“Art is not just for studio art majors, it’s for everyone,” Stula says. Matheou agrees, “We want people to realize that artists, engineers, and scientists use a little bit of the same thought process. We just label something as art or as engineering, but it’s just a label. The way people think, create, and communicate on a fundamental level is the same. I want people to start making these connections, especially our students who are going to create and work in the world in the future.”