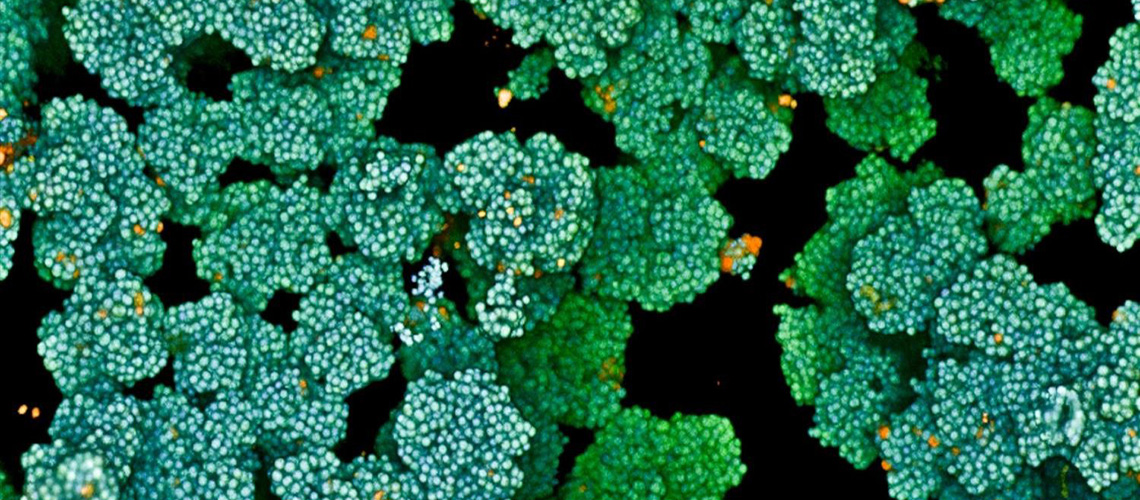

Bed bugs may have been humanity’s first pest, according to groundbreaking research from Virginia Tech. The study suggests that these resilient insects have maintained a close relationship with humans since they first hopped off bats and onto Neanderthals around 60,000 years ago.

The research, published in Biology Letters, highlights a fascinating divergence in bed bug populations. While the adventurous bugs that transitioned to human hosts have thrived, their counterparts that remained with bats have seen a decline since the Last Glacial Maximum, approximately 20,000 years ago.

Evolutionary Insights from Genome Sequencing

A team led by Virginia Tech researchers conducted a comprehensive comparison of the whole genome sequences of these two distinct bed bug lineages. Their findings provide insights into the demographic patterns of bed bugs and suggest that the human-associated lineage may be the first true urban pest.

“We wanted to look at changes in effective population size, which is the number of breeding individuals contributing to the next generation, because that can tell you what’s been happening in their past,” explained Lindsay Miles, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral fellow in the entomology department at Virginia Tech.

“The human-associated lineage did recover and their effective population increased,” Miles noted, highlighting the contrast with the bat-associated lineage that continues to decline.

Human Expansion and Bed Bug Proliferation

The study underscores the historical and evolutionary relationship between humans and bed bugs, which could inform models predicting the spread of pests and diseases as urban populations expand. As humans established large settlements, such as Mesopotamia around 12,000 years ago, the bed bugs that had hitched a ride with them began to flourish.

“Modern humans moved out of caves about 60,000 years ago,” said Warren Booth, an associate professor of urban entomology. “There were bed bugs living in the caves with these humans, and when they moved out, they took a subset of the population with them, resulting in less genetic diversity in the human-associated lineage.”

This transition marked the beginning of an exponential growth in the effective population size of the human-associated bed bugs, paralleling human urban expansion.

Genetic Evolution and Insecticide Resistance

The research provides a foundation for further study of the 245,000-year-old lineage split between the two bed bug populations. Although genetically distinct, the lineages have not evolved into separate species. Researchers are keen to explore the recent evolutionary changes in the human-associated lineage compared to their bat-associated counterparts.

“What will be interesting is to look at what’s happening in the last 100 to 120 years,” Booth remarked. “Bed bugs were common in the old world, but after the introduction of DDT for pest control, populations crashed. They were thought to be eradicated, but within five years, they started reappearing and resisting the pesticide.”

Booth, Miles, and graduate student Camille Block have already identified a gene mutation that may contribute to insecticide resistance, a discovery that could have significant implications for pest control strategies.

Collaborative Efforts and Future Research

This research was a collaborative effort involving experts from Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Arkansas, University of Texas at Arlington, Harvard University, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and the Czech University of Life Sciences.

As the study progresses, researchers aim to delve deeper into the genomic evolution of bed bugs and their resistance to insecticides, which remains a persistent challenge in urban pest management.

The implications of this research extend beyond understanding bed bug evolution; it offers insights into how urbanization influences pest populations and their adaptation strategies, potentially guiding future pest control measures.