If there’s one thing Tasnim Jara never imagined she’d be doing, it’s instructing her fellow Bangladeshis on how to prevent bleeding to death from police gunfire. In August 2024, the Oxford-educated medical doctor found herself posting a video online for precisely this purpose. Dr. Jara, 30, had been watching the escalating violence in Bangladesh from her phone while working in Cambridge, UK. A student-led uprising against the country’s authoritarian prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, had erupted, met with state-sanctioned violence.

As the protests intensified, Dr. Jara realized she could contribute from afar. “I found myself trying to scour for everyday items that people could carry in their backpacks when they go to these protests and if their friend gets shot, what they can do to stop the bleeding before they’re able to get their friend to the hospital,” she explained to Foreign Correspondent. She shared videos with her 11 million social media followers, advising them to carry gauze, tampons, and nappies to control blood flow and save lives.

Eventually, Hasina fled Bangladesh, igniting a new political movement aimed at radically transforming the nation. Dr. Jara saw this as a chance to effect change and returned to Bangladesh to help establish the National Citizen Party (NCP), the country’s first student-led political party. “I wanted to contribute in whatever way I can in changing our political culture,” she said.

From Student Politics to Parliament

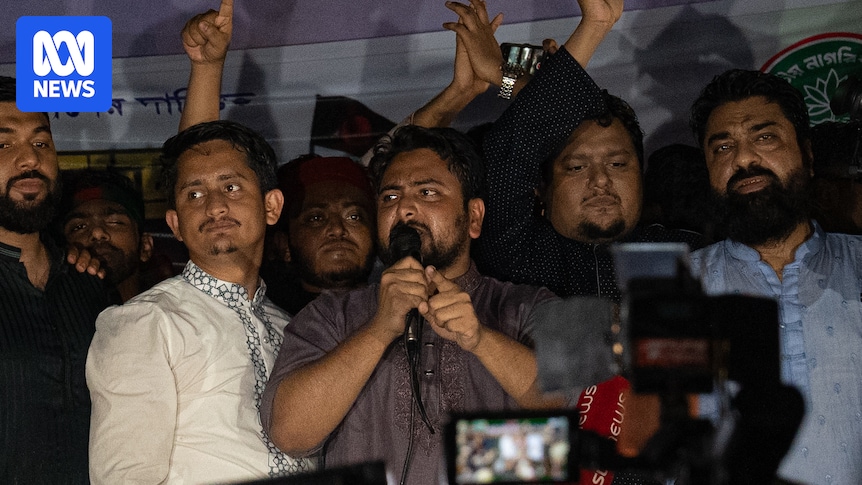

On a humid Friday evening in July, excitement filled the air in Khulna, a city five hours south of Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka. Crowds gathered, eager to meet the young members of the NCP, including Dr. Jara, as they paraded through the streets. It was a reception fit for rock stars, but these were not musicians; they were political pioneers on a nationwide tour.

The student uprising that birthed the NCP began in June 2024 at Bangladesh’s public universities, sparked by a government job quota perceived as favoring allies of Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League. The movement gained momentum as police and the Awami League’s student wing unleashed violence on protesters. A viral video of a student being shot with rubber bullets at close range fueled nationwide outrage.

What followed was a mass uprising driven by nearly 16 years of resentment towards Hasina, known for corruption, rigged elections, and human rights abuses. She responded with deadly force, resulting in 1,400 deaths, according to United Nations estimates. On August 5, with protesters surrounding her residence, Hasina fled to India, leaving a power vacuum and questions about the future.

Taking on the Political Establishment

The student protest leaders hoped the rare moment of national unity would lead to reform and democracy. However, they soon realized established political parties weren’t taking their dream for a “new Bangladesh” seriously. This realization led to the formation of the NCP. “The aspiration from people [was] that the country would not stay how it was but there will be fundamental changes to how the country is being run,” said Dr. Jara, now the party’s senior joint member secretary.

The NCP faces significant challenges, including competition from established parties like the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which has held government multiple times before. While Bangladesh’s youth dream of radical change, the BNP is favored to win the upcoming election.

“I have respect for their views, that’s fine,” said senior BNP member Amir Khosru. “But let the test be the people of Bangladesh. The people of Bangladesh will decide what kind of Bangladesh they want to see.”

Detours on the Path to Democracy

Despite enthusiasm for the upcoming election, many Bangladeshis are weary after a year of perceived inaction. Economics graduate and student activist Prapti Taposhi, 24, put everything on the line during the uprising. For her, the movement wasn’t just about job quotas or ousting Hasina; it was about a freer, fairer Bangladesh.

One significant roadblock has emerged: the National Consensus Commission’s proposal to change the constitution’s secular clause to “religious freedom and harmony.” Some fear this could lead to Islamic laws becoming state laws. Prapti has noticed a shift in religious attitudes since Hasina’s fall, with the interim government being more tolerant of “Islamist extremist voices.”

Assistant Professor of Bangla, Nadira Yeasmin, has faced backlash from conservative religious groups for her feminist advocacy. She’s on leave while her college investigates accusations of being “anti-Islam.” “If that case goes against me, then I will lose my job,” she said. “We had expected that we would build a beautiful country. I feel like that possibility has largely slipped out of our hands.”

While Nadira and Prapti are disappointed, they remain hopeful. Prapti believes the dream of a democratic Bangladesh is not dead but unfulfilled. “Bangladesh should be for everybody, and we should be in the street until the country is for everybody,” she declared.