In 2021, Caragh McMurtry earned a coveted spot on Great Britain’s rowing team for the Tokyo Olympics, a testament to her illustrious career marked by multiple World Cup and World Championship medals. Yet, beneath the surface of her achievements lay a struggle with interpersonal dynamics that often led to friction with teammates and coaches.

“I’m very honest, blunt, and straight to the point,” Caragh explains. “I think what made it hard for people to understand me was my need to break everything down … to understand ‘why’. I couldn’t just take something for granted, and that would rub coaches up the wrong way. They’d think I was undermining them or being facetious.”

Her Olympic debut at Tokyo 2020 was marred by what she perceived as a “lack of transparency” in decision-making. Caragh felt that some athletes were favored based on their ability to “promote” themselves rather than on objective criteria. “I have a massive justice complex,” she says. “It wouldn’t even necessarily be about me. If I saw something and it wasn’t right, I’d get really hung up on it. That shouldn’t be a problem if things are fair … but unfortunately, in elite sport, the system is very hierarchical.”

Sensory Challenges and Misdiagnosis

Beyond interpersonal issues, Caragh faced sensory challenges. The gym, which she described as a “hellscape,” was filled with loud music that made the floor shake. The one place she could seek solace—the cafe or “crew room”—was overwhelmingly bright and filled with strong smells.

“I wanted to take myself away to recharge, but then I’d be seen as antisocial,” she reflects. It was only later in her career that she recognized these challenges as characteristic of her autism, a diagnosis she received after initially being misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder.

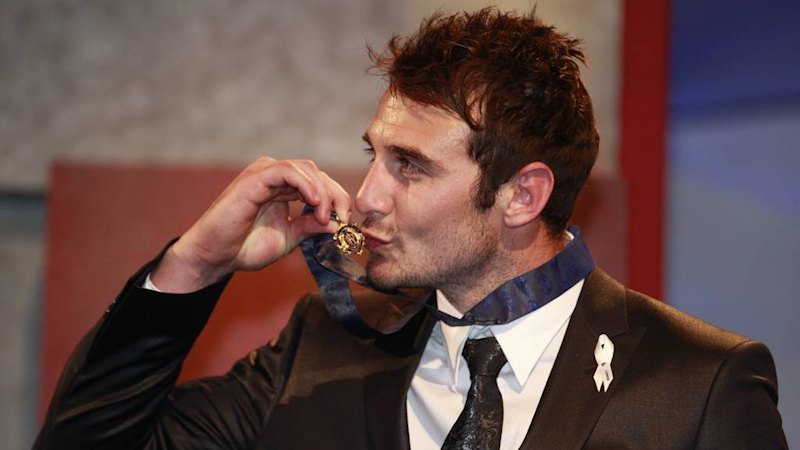

“Throughout her career, Caragh faced challenges she now recognizes as characteristic of her autism.” (Getty Images: Mark Runnacles)

This misdiagnosis led to a disruptive five-year period during which she was placed on several medications, including lithium, which hampered her performance and well-being. She went winless during this time, only returning to the podium after discontinuing her medication, taking silver in the Women’s Four at the 2021 Rowing World Cup before competing in the Women’s Eight at Tokyo.

Embracing Autism and Its Advantages

Now retired and the founder of Neurodiverse Sport, a not-for-profit organization, Caragh is committed to ensuring that neurodivergent athletes not only survive but thrive in elite sports. Initially, she struggled to embrace her autism diagnosis, fearing it would further set her apart.

“It made sense, but I was like, ‘I wonder what people will think of that? It’s another thing to set me apart. I’ve gone from bipolar to autism, wonderful,'” she recalls. However, over time, she realized that autism had been “defined by people who are not autistic.”

“I’ve grown up with all the messaging and stereotyping that everyone else had about autism,” Caragh says. “But when I read about autism from the perspective of people who are autistic, it made me feel a lot better about it.”

Looking back, Caragh acknowledges that autism was critical to her success as an elite athlete. Traits such as “obsessiveness, hyperfocus, attention to detail and pattern recognition” played to her advantage. “To be an elite athlete, you need a spiky profile, you need to be extreme in some way,” she asserts.

Expert Insights on Neurodiversity in Sport

Dr. Erin Hoare, a psychologist and researcher specializing in neurodiversity, supports the idea that individuals with ADHD and autism may have an edge in elite sports. “The examples we often talk about are a preference for repetitive routines, the ability to hyperfocus on a goal, and rapid reaction to stimuli,” Dr. Hoare explains. “Their strengths could ultimately lead to a competitive advantage.”

“There is some epidemiological evidence to suggest neurodivergent people are over-represented in elite sport, although more research is needed.” (Supplied: Erin Hoare)

Dr. Hoare points out that women and girls are often underdiagnosed due to gendered biases in medicine and science, which historically have focused on a specific demographic that excludes women. “With ADHD and autism specifically, diagnostic criteria have largely been based on the experiences of men,” she notes.

Women, she adds, are adept at “masking” or “camouflaging” their neurodivergence, using compensatory behaviors to meet social expectations. This can lead to them being undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, as was the case with Caragh.

Building Inclusive Sporting Environments

Caragh now dedicates much of her time to educating sporting organizations on creating inclusive environments. She advocates for a “traits-based” approach to athlete support, recognizing that everyone has different thinking and learning styles, as well as sensory preferences.

“You can do so much to help people, it’s just about being flexible, innovative, and meeting people where they’re at,” Caragh explains. “It’s also about challenging your own assumptions and not putting people in boxes.”

“Neurodivergent people have incredible strengths and differences that are potentially an untapped resource.” (Dr. Erin Hoare)

Dr. Hoare endorses this approach, emphasizing the importance of collaborating with autistic athletes to understand their experiences and preferences. “The starting point is talking directly to autistic athletes, working in closer partnership and collaboration with them about their experiences and having curiosity about their world view,” she says.

As Caragh continues her mission to foster inclusivity in sports, her journey highlights the potential for neurodivergent athletes to not only overcome challenges but also harness their unique strengths to gain a competitive edge.