Australia’s federal public service is a sprawling entity, employing 198,000 individuals across various departments. This includes 35,200 in Services Australia, 21,400 at the Australian Taxation Office, and 16,000 in Home Affairs. The Department of Defence alone accounts for 20,500 public servants, alongside nearly 58,000 uniformed personnel not counted in the public service tally. Yet, the complexity of governance extends beyond mere numbers.

The intricate web of politicians from Canberra to local councils oversees these operations, while millions of laws and regulations—often conflicting between states—add layers of complexity. Businesses operating nationwide face up to 36 different versions of payroll tax, a situation Business Council of Australia chief executive Bran Black likens to the challenges of the moon landings.

“Complying with these different payroll rates and thresholds across the country strikes me as more difficult than the moon landings,” says Bran Black.

Economic Strain and Federation Reform

At a recent economic roundtable, the convoluted structure of Australia’s federation was a prominent topic. Black emphasized that the system is detrimental to both businesses and citizens, urging for federation reform to improve quality of life.

“People genuinely have no understanding or a sense of our falling quality of life, which is only going to continue if there’s no change in direction. Federation reform is absolutely critical to turning this around,” he asserts.

New South Wales Premier Chris Minns concurs, acknowledging the economic impact of the federation’s current state. He highlights that despite changes in political leadership and ideologies, the systemic gridlock persists.

“It’s the same gridlock, same problem,” Minns states.

Competitive Federalism: A Double-Edged Sword

Queensland’s LNP leader, David Crisafulli, advocates for “competitive federalism,” where states serve as economic experiments. However, he admits that the federation’s structure imposes significant economic costs.

Historically, Australia’s federation has faced challenges, such as the rail gauge issue between NSW and Victoria, resolved only in 1962. Yet, rail operators still grapple with state-specific approvals and communication systems, costing time and money.

“Hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions, could be saved if we did things better,” says Natalie Currey of the Australasian Railway Association.

Infrastructure and Regulatory Challenges

Beyond rail, Australia’s infrastructure faces hurdles, exemplified by the e-bike standards debacle. A 2021 federal change in e-bike definitions has led to safety concerns and market isolation in NSW, where differing standards complicate legal compliance.

“Australia does not have an e-bike manufacturing industry. Major international e-bike brands have already pulled out of the NSW market,” notes Peter Bourke of Bicycle Industries Australia.

Similarly, bike helmet standards have seen a shift, with most states adopting international standards, yet Tasmania remains an outlier, potentially leading to shortages.

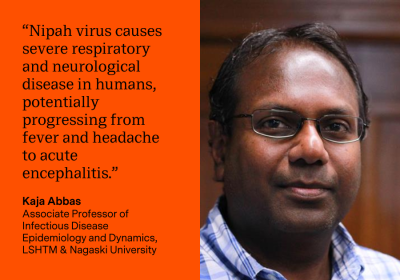

Health and Housing: A Federation in Crisis

Health services epitomize the federation’s duplication issues. South Australian Premier Peter Malinauskas highlights the inefficiencies, with patients occupying costly hospital beds instead of aged care facilities due to federal-state responsibilities.

“The whole problem is just going to get worse,” Malinauskas warns.

Housing, another critical area, suffers from federal, state, and local governance overlap. Despite federal funding, states struggle with joint funding requirements, exacerbated by environmental law constraints.

“The single biggest issue at the moment is migration, housing and infrastructure and how they are connected. They show just how the federation is completely broken,” argues Daniel Wild of the Institute of Public Affairs.

Fiscal Imbalance and the GST Dilemma

Financially, the federation is marked by a “vertical fiscal imbalance,” with states responsible for over half of government spending but raising only a quarter of the revenue. This imbalance has historical roots, with federal control over income tax since WWII and subsequent shifts in financial responsibilities.

“To cut a long story short, we do all the work and they collect all the money,” says Minns.

The GST, intended as a growth tax, has fallen short due to exemptions and changing economic dynamics. Analysis suggests states could gain billions more if GST revenues aligned with GDP growth, funding major infrastructure projects.

“If the GST worked properly, these projects could be fully funded and built much more quickly,” says Matt Grudnoff of the Australia Institute.

Looking Forward: Reform and Resilience

Despite the challenges, there is potential for reform. University of Queensland’s Flavio Menezes highlights the inefficiencies of a fragmented economy, urging for streamlined processes to reduce costs.

“Federalism as it operates in Australia may be suboptimal, but it’s not bad enough to push people to do something about it,” says Alan Fenna of Curtin University.

Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers acknowledges the need for reform, indicating ongoing efforts to address these systemic issues. As Australia grapples with stagnating living standards and rising government debt, the call for federation reform grows louder.

The path forward requires balancing historical structures with modern needs, ensuring that governance supports economic growth and quality of life for all Australians.