From Melbourne’s proposed Outer Metropolitan Ring Road to Sydney’s recently completed WestConnex, Australia’s ongoing investment in large-scale road projects highlights a persistent reliance on car-centric infrastructure. This trend persists despite the urgent need to address climate change, as articulated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC warns that such developments “lock in” emissions, committing societies to greenhouse gas outputs for decades.

Australia’s approach to urban transport, heavily focused on expanding freeway networks, appears misaligned with state planning policies that advocate for less-polluting transport modes. These include train and tram extensions, improved bike lane infrastructure, and enhanced pedestrian pathways. The contradiction raises concerns about the nation’s ability to meet its climate targets, particularly the commitment to achieve net zero greenhouse emissions by 2050.

The Impact of Mega Road Projects

Despite the pressing need to reduce emissions, several mega road projects are underway or planned in Australian cities. These projects threaten to undermine efforts to promote cleaner transport alternatives. For instance, the Outer Metropolitan Ring Road in Melbourne, a 100-kilometre freeway encircling the city’s north and west, is projected to cost A$31 billion, making it one of the most expensive road projects in Australia.

In 2009, the Victorian government allowed the project to proceed without an “environmental effects statement,” which would have assessed its climate impacts. The decision was justified by the project’s passage through previously disturbed land and the consideration of sustainability in state planning blueprints. However, given the significant potential contribution to transport emissions, there is a strong argument for reversing this exemption and subjecting the project to rigorous environmental scrutiny.

“Transport emissions are set to become Australia’s largest source of emissions by 2030, making it imperative to reconsider the approval processes for major road projects.”

Challenges in Public Consultation

Historical examples, such as Melbourne’s East West Link and Sydney’s WestConnex, illustrate issues with public consultation on major road projects. In the case of WestConnex, the definition of “public interest” was criticized for inadequately addressing climate change concerns. A 2017 Victorian Auditor-General Report highlighted a power imbalance between project proponents, who often have legal representation, and community participants, who do not.

To ensure transparency and public involvement, emissions reduction must become central to the policies governing Australia’s built environments. This includes integrating climate action and emissions reduction goals into state planning blueprints, which currently consider land use and transport together but often overlook the broader climate implications.

Integrating Climate Goals into Urban Planning

Residents in Australia’s capital cities are largely car-dependent, with limited access to climate-friendly transport modes like walking and cycling. The IPCC recommends strategies such as infill development, increasing urban density, improving public transport, and supporting active transport options to minimize emissions in cities.

While state planning documents in Victoria, New South Wales, and Queensland set goals for building homes near public transport and services, the integration of emissions reduction and net zero targets is often superficial. Federal guidelines on transport planning also fall short in this regard, allowing major road projects to proceed without directly considering their impact on emissions.

“Globally, roads account for 69% of transport emissions, a figure that continues to grow, underscoring the need for a shift in transport policy.”

Exploring Alternative Solutions

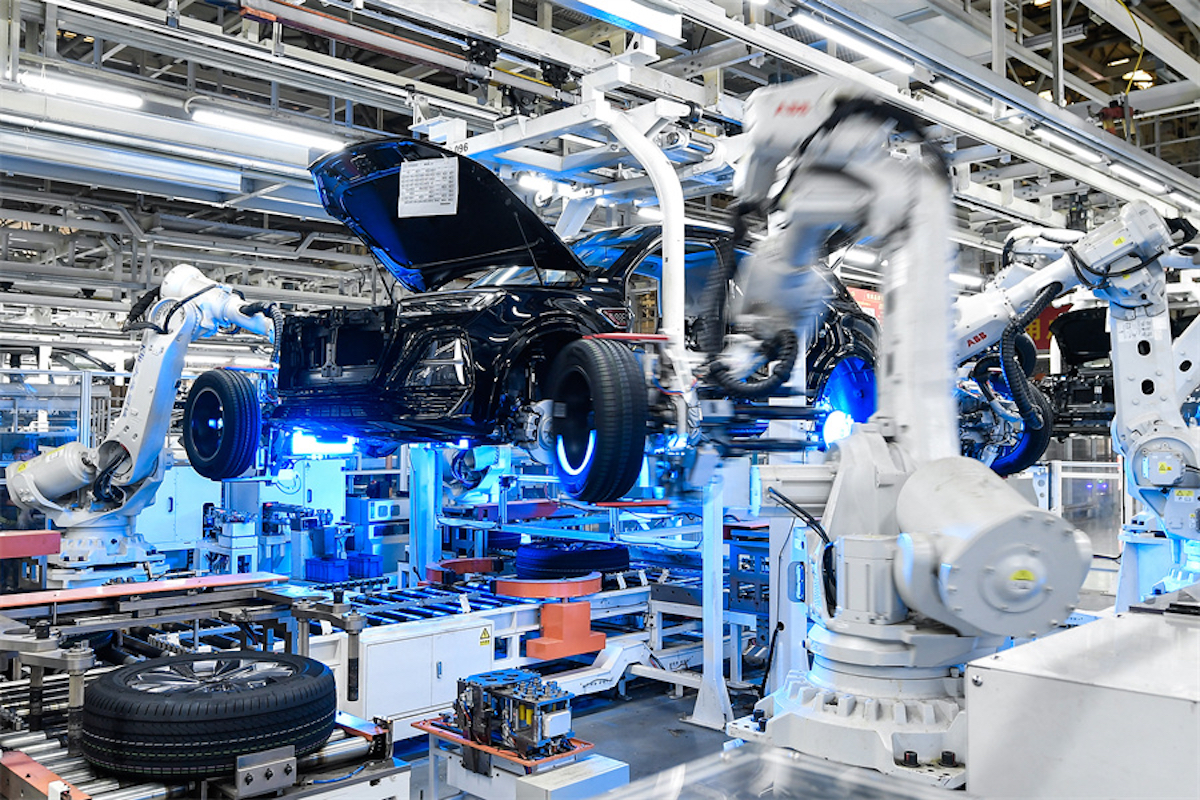

Beyond urban planning policies, other government measures can help reduce vehicle emissions. The federal government’s fuel efficiency standards, introduced this year, aim to curb transport emissions, although some experts argue the policy does not go far enough. Additionally, the National Electric Vehicle Strategy marks progress, but Australia still lags in electric vehicle adoption, necessitating further efforts.

As Australian cities expand, the demand for travel will increase. However, relying on new freeway projects is not a sustainable solution. Instead, reform is needed to place emissions reduction at the core of transport investment decisions, ensuring that Australia can meet its climate commitments and foster a more sustainable urban future.