More than two in five Australians will face a cancer diagnosis by the age of 85, leading to the deaths of 146 people daily. However, recent advancements by Australian researchers at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research are setting the stage for a significant reduction in cancer fatality rates. These efforts, particularly in 2025, have positioned Australian scientists at the forefront of global cancer research.

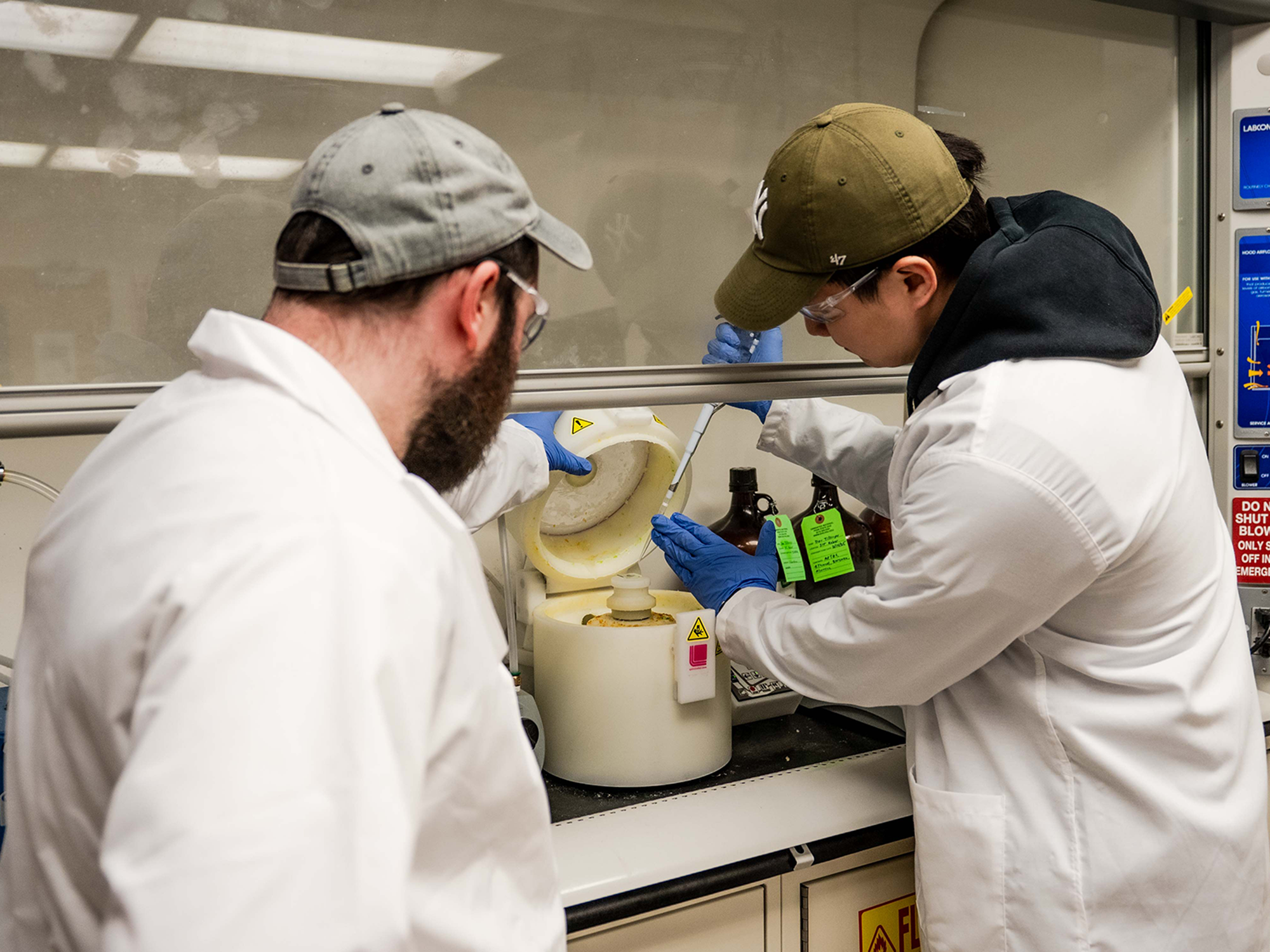

Under the leadership of Associate Professor Christine Chaffer and Professor Alexander Swarbrick, the research labs have become world leaders in understanding the complexities of breast cancer cells. This progress has been made possible by a substantial $25 million grant from the National Breast Cancer Foundation.

Innovative Approaches to Breast Cancer Treatment

Chaffer’s team is focused on developing treatments for breast cancer that reemerges post-treatment, which is often more aggressive and challenging to manage. “They just have morphed into more aggressive versions of their former selves,” Chaffer explained in an interview with 7NEWS.com.au. Her research aims to decipher the fundamental mechanisms behind these changes in cancer cells.

Chaffer noted significant achievements this year, including a method to prevent cancer cells from evolving into chemotherapy-resistant forms. Currently undergoing its first therapeutic trial, this new treatment targets patients with triple-negative and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, which are notoriously difficult to treat.

“This is really a game-changing approach to be able to say that we can actually stop resistance from happening,” Chaffer stated. “That’s our ultimate goal.”

The Breast Cancer Cell Atlas: A New Frontier

Contrary to the common belief that tumors stem from a single rapidly duplicating cell, Swarbrick’s lab is working on the Breast Cancer Cell Atlas, aiming to identify the diverse cell types that constitute breast cancer. “The aim here is to build the world’s most detailed cellular map of breast cancer,” Swarbrick said.

Understanding the organization of cells within breast cancers is crucial for comprehending how tumors grow, evolve, and respond to therapy. Swarbrick’s research has identified several cell types within breast cancers that are pivotal in organizing anti-tumor immune activity.

“Research this year has identified several cell types that are found within breast cancers that would probably be lost if we weren’t able to study the tumour cell by cell,” he noted.

Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Personalized Treatment

The collaboration between Chaffer and Swarbrick extends to the use of artificial intelligence, provided by a team at Yale University, to identify individual cells. This approach allows for personalized treatments tailored to target specific types of cancer, moving away from broad treatment strategies of the past.

This method is integral to the lab’s AllClear program, which aims to identify and eradicate cells likely to cause relapse before they become cancerous. “We want to be able to come up with that treatment right at the outset of a patient’s breast cancer diagnosis,” Chaffer emphasized.

Both researchers acknowledge that while significant progress has been made, there is still a long journey ahead. The techniques developed could potentially be applied to other types of cancer, offering hope for broader cancer research advancements.

“I think that the opportunities are enormous and it’s a really, really exciting time to be in research,” Chaffer expressed.

Encouraging Early Detection

Chaffer also stressed the importance of early detection in improving survival rates for breast cancer. “If you get diagnosed early, the chances of survival are really good these days. The treatments and surgery are really effective,” she advised.

The strides made by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research not only promise a brighter future for breast cancer patients but also pave the way for innovative approaches to tackling various cancers worldwide.