Additive manufacturing, more commonly known as 3D printing, is poised to become a critical technology for any long-term settlement on another world. Its ability to transform generic inputs, such as plastic strips or metal powder, into the precise tools astronauts need is revolutionary. However, the chemistry behind these technologies is complex, and their applications are varied, ranging from creating bricks for settlements to producing everyday items like cups and toothbrush holders.

New Research on Mars 3D Printing

A recent study, available in pre-print on arXiv by researchers Zane Mebruer and Wan Shou from the University of Arkansas, delves into a specific aspect of 3D printing that could save millions of dollars on Mars missions. Their research focuses on a component of a metal 3D printing process known as selective laser melting (SLM), which is used to print 316L stainless steel—a material widely used across various industries.

Challenges of Shield Gases on Mars

On Earth, the oxygen-rich atmosphere can oxidize the material being printed, resulting in a brittle end product. To prevent this, 3D printers employ a “shield gas” to exclude air and its disruptive oxygen from the vicinity of the print. Typically, this shield gas is argon, an inert noble gas that is expensive and scarce on Mars. This poses a challenge for mission planners, as importing argon from Earth involves significant costs. However, the new study proposes using Mars’ atmosphere as a shield gas instead.

At first glance, this might seem counterintuitive, given that Mars’ atmosphere is primarily composed of carbon dioxide, which contains oxygen. Since the purpose of a shield gas is to keep oxygen away, using a gas that contains it might seem impractical. Surprisingly, the study finds otherwise.

“While the CO2 didn’t perform as well as the argon, it was acceptable enough for use in a wide variety of non-critical metal infrastructure parts, like hinges or door handles.”

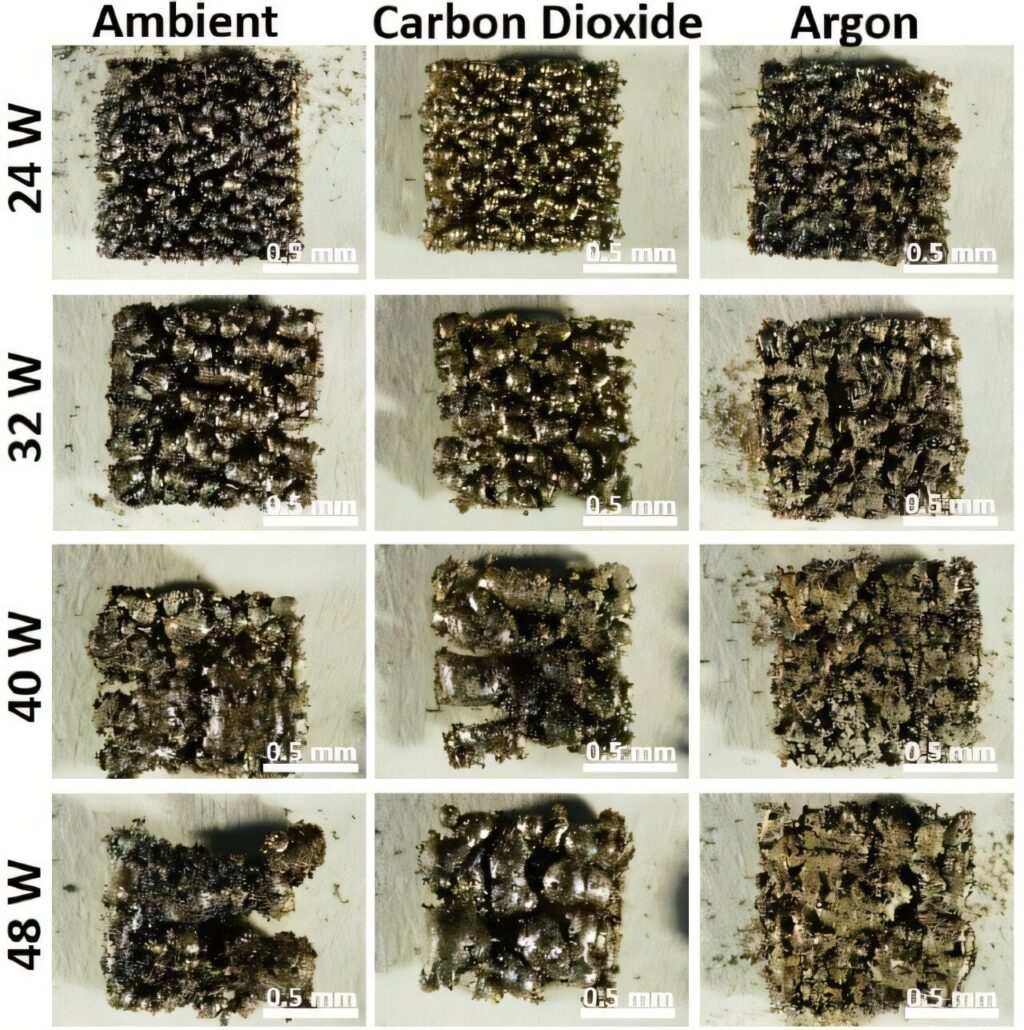

In tests where solid square layers were printed, argon demonstrated around 98% effectiveness in maintaining shape, whereas carbon dioxide achieved approximately 85% “area retention.” In contrast, ambient air resulted in less than 50% effectiveness, rendering parts produced under it essentially useless.

Why Carbon Dioxide Can Work

The success of carbon dioxide as a shield gas lies in its behavior at high temperatures. During the laser melting process, CO2 dissociates, meaning reactive O2 is introduced into the system. However, the partial pressure of oxygen in a pure CO2 environment is less than that in Earth’s nitrogen-rich atmosphere. This means that while some oxygen is present, it is not as actively forced into the melt pool, reducing oxidative damage.

The study found that even parts printed in argon contained some oxygen. Parts printed with CO2 had about 1.6 times more oxygen content than those printed with argon, but still significantly less than parts printed in ambient air, making them functionally useful.

Implications for Space and Industry

This research has implications beyond space exploration. Argon is costly regardless of its source, so the potential to use a cheaper substitute like CO2 and achieve “good enough” results could save metal 3D printing companies significant costs in consumables. Whether companies are willing to compromise on the aesthetic quality of their prints is another matter.

“Astronauts on a planet, nine months of travel time away from the nearest door handle manufacturer, don’t care about aesthetics as long as parts work.”

For astronauts, the ability to set up a printer outside their habitat and utilize the planet’s atmosphere, which would otherwise be hostile, represents a small but significant step towards in-situ resource utilization.

This innovative approach could bring the dream of a long-term settlement on Mars one step closer to reality, highlighting the potential for human ingenuity to overcome the challenges of space exploration.