Ant colonies function as highly coordinated “superorganisms,” with individual ants working together much like the cells of a body to ensure collective health. Researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) have made a groundbreaking discovery: terminally ill ant brood emit an odor that signals their impending death and the risk they pose to the colony. This sophisticated early warning system, detailed in a study published in Nature Communications, allows for the rapid detection and removal of pathogenic infections.

While many social animals conceal their illnesses to avoid social exclusion, ant brood take the opposite approach. When facing an incurable infection, ant pupae actively emit an alarm signal to warn the colony of the contagion risk they present. Upon receiving this signal, worker ants respond by unpacking the terminally ill pupae from their cocoons, creating small openings in their body surface, and applying formic acid, their antimicrobial poison. This self-produced disinfectant kills the pathogens but also results in the pupa’s demise.

Altruistic Self-Sacrifice in Ant Colonies

The study, led by Erika Dawson, a former postdoc in the Social Immunity research group at ISTA, reveals that this self-sacrifice is beneficial to the signaler as well. “By warning the colony of their deadly infection, terminally ill ants help the colony remain healthy and produce daughter colonies, which indirectly pass on the signaler’s genes to the next generation,” Dawson explains.

The research, conducted in collaboration with chemical ecologist Thomas Schmitt from the University of Würzburg in Germany, marks the first description of altruistic disease signaling in social insects. If a fatally ill ant were to conceal its symptoms and die undetected, it could become highly infectious, endangering the entire colony. Active signaling of the incurably infected allows for effective disease detection and pathogen removal by the colony.

The “Find-Me and Eat-Me” Signal

Ant colonies operate as a “superorganism,” with non-fertile workers taking on tasks related to colony maintenance and health, similar to cell specialization in the human body. In both organisms and superorganisms, reproductive and non-reproductive components are interdependent, making cooperation crucial. Individual ants collaborate closely, even engaging in altruistic self-sacrifice for the colony’s benefit.

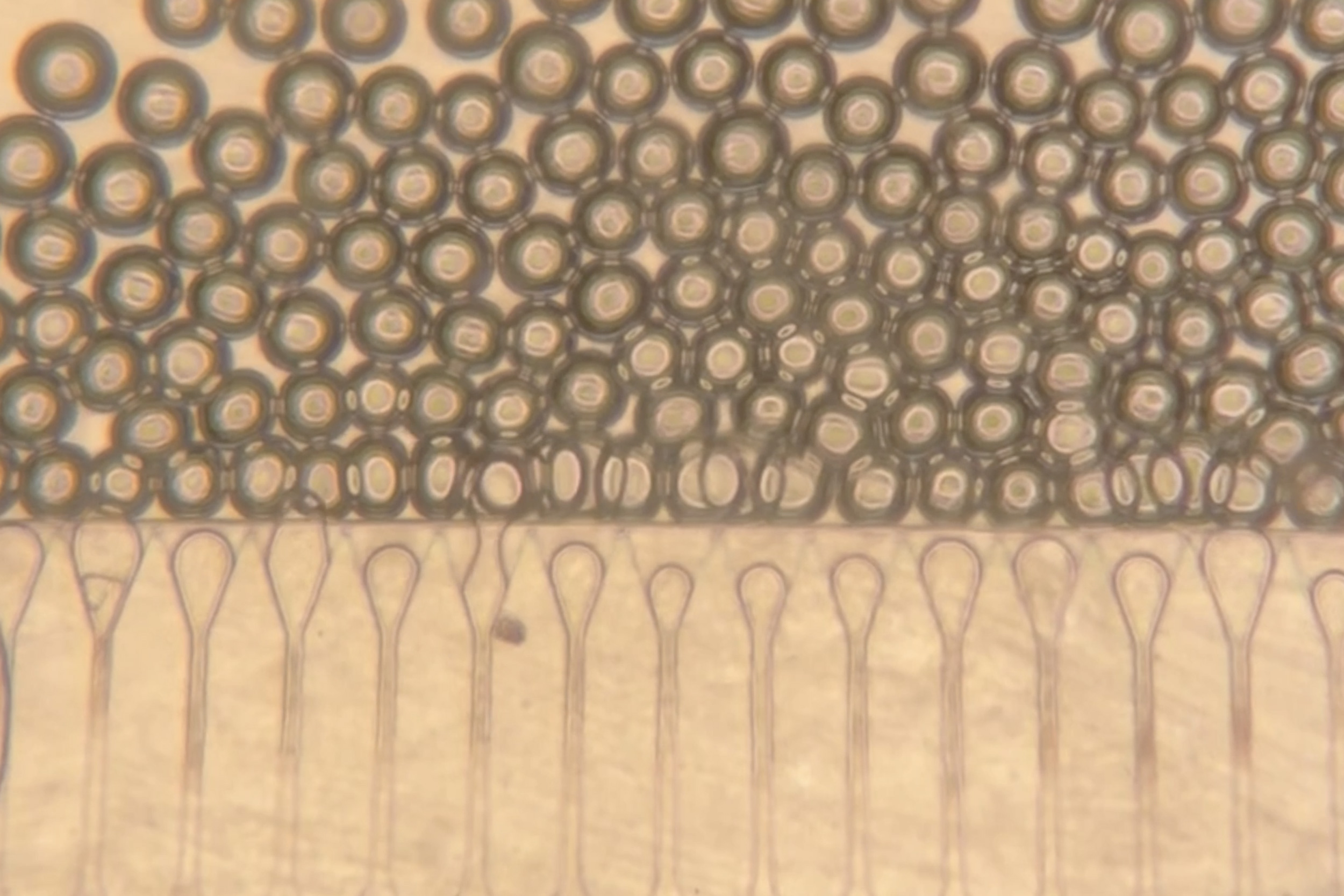

Cremer explains that while adult ants approaching death leave the nest to die outside and workers exposed to fungal spores practice social distancing, this is not an option for immobile ant brood. Like infected cells in tissue, ant pupae rely on external assistance to safeguard the colony. They emit a chemical signal that attracts either the body’s immune cells or the colony’s workers, allowing these helpers to detect and eliminate them as potential infection sources. This is known as the “find-me and eat-me signal.”

“The signal must be both sensitive and specific,” says Cremer. “It should help identify all terminally-sick ant pupae but be precise enough to avoid triggering the unpacking of healthy pupae or those capable of overcoming the infection with their immune system.”

Changes in Pupal Scent Profile

Schmitt, whose research focuses on chemical communication in social insects, notes that workers specifically target individual pupae out of the brood pile. “This means the scent cannot simply diffuse through the nest chamber but must be directly associated with the diseased pupa,” he explains. The signal consists of non-volatile compounds on the pupal body surface.

Researchers found that the intensity of two odor components from the ants’ natural scent profile increases when a pupa is terminally ill. To test if this odor change alone could trigger the workers’ disinfection behavior, they transferred the signal odor to healthy pupae. The results were conclusive: the altered body odor of fatally infected pupae served the same function as the ‘find-me and eat-me’ signal of infected body cells.

Signaling Only in Uncontrollable Cases

Interestingly, ants do not signal infection indiscriminately. “Queen pupae, which have stronger immune defenses than worker pupae and can limit the infection on their own, were not observed to emit this warning signal,” Dawson explains. “Worker brood, unable to control the infection, signaled to alert the colony.”

By signaling only when an infection becomes uncontrollable, the sick brood enable the colony to respond proactively to real threats. This approach ensures that individuals capable of recovery are not sacrificed unnecessarily. “This precise coordination between the individual and colony level is what makes this altruistic disease signaling so effective,” Cremer concludes.

Implications for Future Research

The discovery of this altruistic signaling in ants opens new avenues for understanding social immunity and disease management in other social organisms. It highlights the complex interplay between individual and collective health, offering insights that could inform studies in fields such as behavioral biology, immunology, and genetics.

As researchers continue to explore these mechanisms, the ant colony’s self-sacrificial strategy may provide valuable lessons for managing disease and promoting health in human societies, where cooperation and early detection are equally critical.