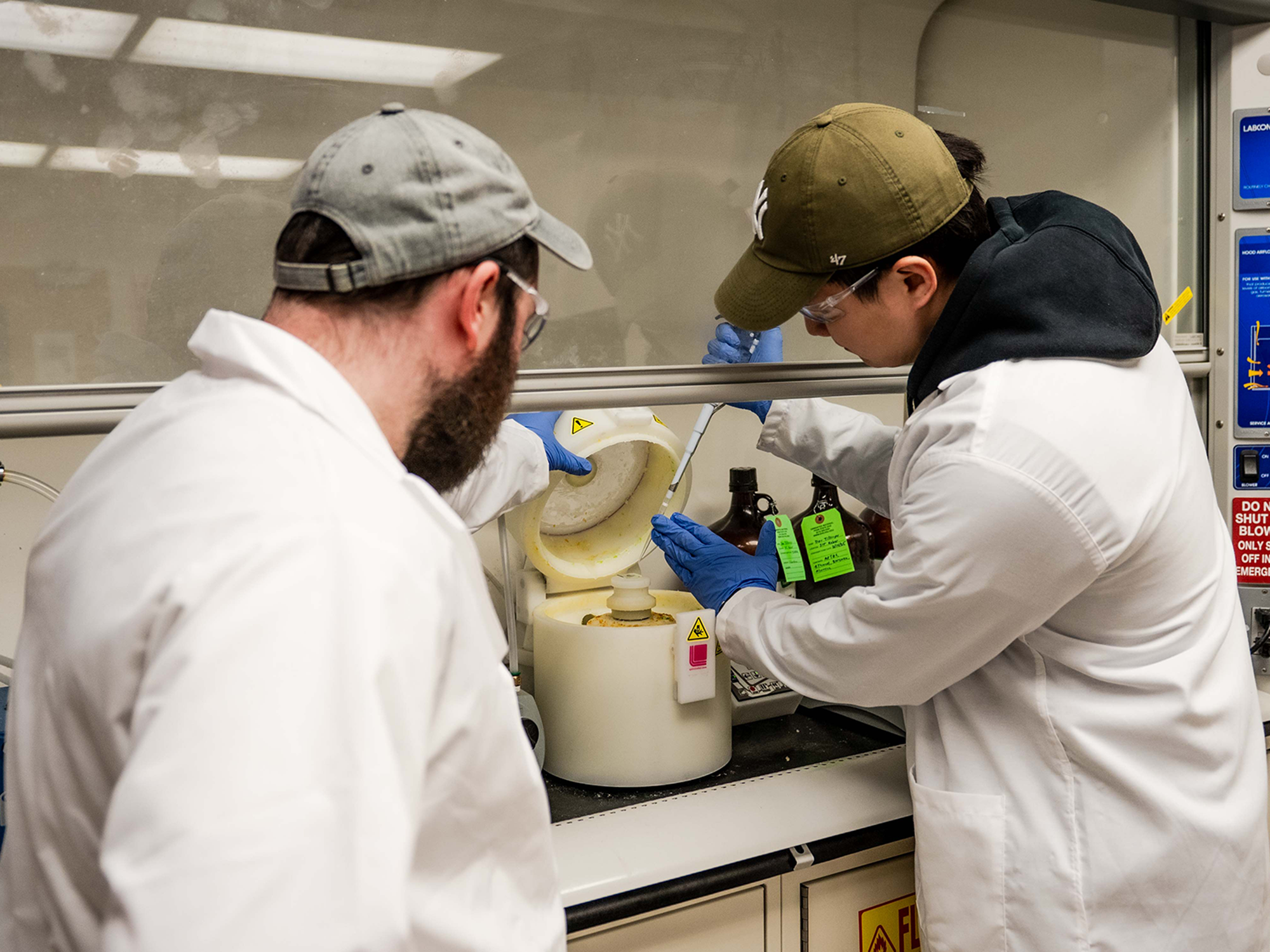

Inside an ice-cold laboratory in Hobart, where temperatures plummet nearly 20 degrees Celsius below zero, a dedicated team of scientists embarks on a groundbreaking mission. Clad in thick puffer jackets and gloves, they carefully extract a one-meter cylinder of ice from an insulated box, freshly arrived from Antarctica.

“In the freezer lab today, we’re cutting the first samples from the ‘Million Year Ice Core’,” explained Joel Pedro, a paleoclimatologist with the Australian Antarctic Division. “And that’s a big moment for us.”

The Ambitious ‘Million Year Ice Core’ Project

For nearly a decade, Dr. Pedro and his team from the Australian Antarctic Program have been meticulously planning this ambitious project. The goal is to extract the world’s oldest continuous ice core from deep beneath the Antarctic ice sheet.

“More than any other archive of climate in the past, ice cores have a range of information that helps you to understand the changes in the total climate system,” Dr. Pedro noted. Ice cores, often described as time capsules, offer a clear picture of Earth’s climate and atmospheric history through tiny air bubbles trapped over millennia.

“Those air bubbles are a sample of the atmosphere in the past that was trapped as snow fell and was then compressed into ice,” Dr. Pedro said.

A Glimpse into Earth’s Ancient Climate

The ice currently under analysis in Hobart originates from a depth of 150 meters, making it nearly 4,000 years old. While significant, this is just the beginning of a much larger mission. The team aims to reach a depth of 3,000 meters, potentially uncovering ice that dates back up to 2 million years.

“We’re hoping to push the climate record back well over a million years,” Dr. Pedro stated, highlighting the project’s potential to unlock unprecedented insights into Earth’s climatic past.

The Grueling Journey to Dome C North

Reaching this point has been a monumental logistical feat. The drill site, Dome C North, lies 1,200 kilometers from the nearest Australian station in Antarctica and 3,000 meters above sea level, where temperatures can drop below -50 degrees Celsius.

Transforming the site into a deep field station required a 10-person team using six tractors to haul nearly 600 tonnes of equipment across the frozen landscape. “In the Australian program, it’s the biggest traverse that we’ve undertaken,” said Chris Gallagher, the traverse leader from the Australian Antarctic Division.

“It’s a very specialized team that has extremely high skills, but also that ability to really get on with each other and care for each other,” Gallagher remarked. “We were like a big family on this trip.”

Celebrating Milestones Amidst Challenges

After enduring multiple blizzards, the team reached Dome C North 18 days after departing from Casey Station. Once the accommodation modules and drill shelter were established, a separate team of scientists flew in to commence the drilling and processing of the ice core.

Chelsea Long, a field assistant, described the extraction of the first section of ice as a momentous occasion. “It was really celebratory when it came out and just finally to see this happening and to touch the ice and measure it, was a real joy,” she said.

For Dr. Pedro, this milestone was a culmination of years of hard work, compounded by delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “The start to the project was easily the most exciting thing that’s happened in my science career,” he reflected. “But at the same time, it’s just the start of the project — we’ve still got 3 kilometers to go.”

Unlocking the Mysteries of Earth’s Climate

Currently, the oldest ice core on record dates back almost 800,000 years. However, a European team, known as Beyond EPICA, recently extracted ice from a depth of 2,800 meters, expected to date back nearly 1.2 million years. The Australian team plans to drill over 200 meters deeper, potentially reaching ice that dates back up to 2 million years.

“If we can get this record − and the modeling suggests Dome C North is the best site in Antarctica for recovering the oldest ice − then we’ll produce data that will stand for decades as the measurement of Earth’s atmosphere and greenhouse gas levels through that period,” Dr. Pedro explained.

Such data could provide crucial insights into why Earth’s ice ages became significantly longer about a million years ago, addressing one of the biggest puzzles in climate science. “It remains one of the biggest challenges in ice core science and climate science to resolve what the cause of that was, and, in particular, what the role of CO2 was in that,” Dr. Pedro added.

Looking ahead, the team plans to resume drilling during the 2025/26 summer, with the goal of reaching the 3,000-meter mark by 2028/29. If successful, the “Million Year Ice Core” project could significantly enhance the accuracy of climate change forecasts, offering a clearer understanding of our planet’s climatic future.