From the deck of an enormous research ship, surrounded by icebergs, Chelsea Bekemeier releases a tethered balloon into the air. She’s stationed deep in the Southern Ocean, just off East Antarctica, where temperatures are well below freezing. This remote location, 5,000 kilometers from the nearest city, Hobart, is a treasure trove for climate scientists like Ms. Bekemeier.

Climate scientist Chelsea Bekemeier journeyed to the Southern Ocean to gather data crucial for improving global climate models. Known as the “engine room” for global weather and climate, the Southern Ocean remains a significant blind spot in climate data. Scientists worldwide are undertaking the arduous journey to this distant part of the Earth to fill in these crucial gaps and enhance climate and weather models.

The Southern Ocean: A Remote Climate Laboratory

“The Southern Ocean is very understudied, mainly because of how difficult and remote it is. We’re hoping to change that,” Ms. Bekemeier explained. Her recent expedition, which concluded last month, was not for the faint-hearted. Based at Colorado State University, it took her over 24 hours of flight time to reach Hobart, followed by a week-long voyage on the Australian Antarctic Division’s RSV Nuyina to reach Denman Glacier, one of East Antarctica’s largest glaciers.

During her nine-week stay on the massive icebreaker, designed to navigate through ice and massive swells, Ms. Bekemeier faced the challenges of a remote and harsh environment. “I was very nervous,” she admitted. “They made it very clear to us after a year of medical and psychological testing that you are in a remote region on a boat. If you need help, we have two doctors, but you really cannot get out. It takes a week if you’re in good condition to get back to land.”

Unpacking Climate Clues from the Clouds

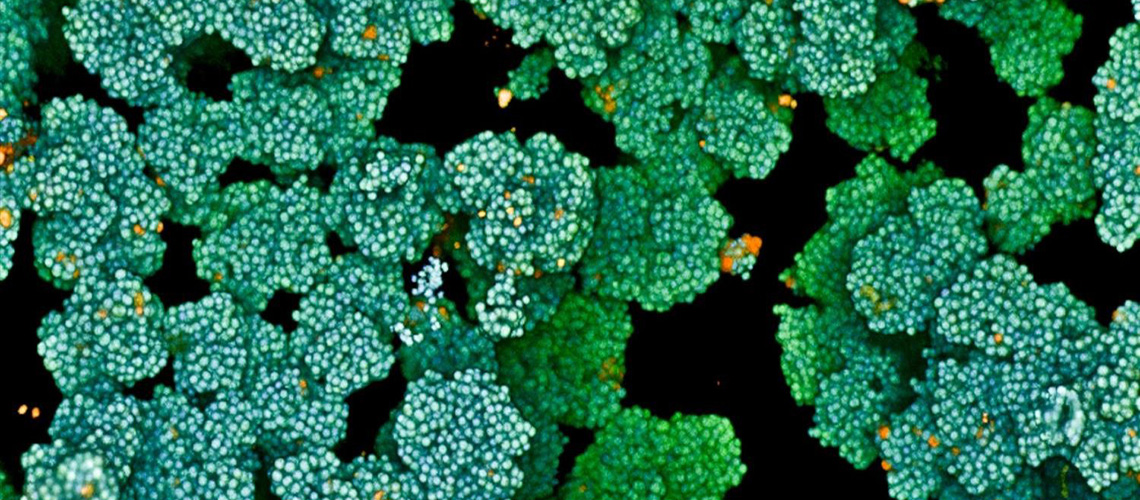

For Ms. Bekemeier, the focus was on the clouds. The balloon she released was equipped with sensors to capture data from within these clouds, which play a crucial role in Earth’s climate system by reflecting sunlight and trapping heat. “Clouds are constantly doing this job of balancing the incoming sunlight,” she noted. “You can see that when you go outside on a hot day and the clouds roll in, and the temperature drops pretty rapidly. Then at night, if it’s really overcast, it actually feels warmer because at night they insulate the planet.”

“The Southern Ocean is the cloudiest region on the planet. It really is important to capture the Southern Ocean and these clouds because they are very pivotal for the future climate of the entire planet.” — Chelsea Bekemeier

Mixed-phase clouds, containing both ice and water, are particularly challenging for climate models to represent accurately. The pristine air of the Southern Ocean, free from pollutants and dust, offers a unique opportunity to study these clouds in their purest form.

Pristine Air: A Window into Pre-Industrial Atmosphere

Meanwhile, CSIRO research scientist Ruhi Humphries has been studying the region’s uniquely fresh air, which offers insights into the impacts of human activity on the atmosphere. “The Southern Ocean, that’s really the cleanest air we have in the world. And it’s the closest we have to that kind of pre-industrial air,” Dr. Humphries explained.

This clean air provides a baseline to understand the broader picture of climate change, away from pollution. “If we want to understand our impact and how to mitigate that effectively, we need to know what the atmosphere looks like without that pollution,” he said. Dr. Humphries is comparing air samples from Kennaook/Cape Grim in Tasmania to those from further south in the Southern Ocean to verify the purity of this baseline air.

Global Implications of Southern Ocean Research

According to both Dr. Humphries and Ms. Bekemeier, the research in the Southern Ocean is vital for understanding global climate change impacts. “The Southern Ocean is vital to the future of our planet,” Ms. Bekemeier emphasized. “Changes to this region will have impacts for the entire planet; impacts on the Antarctic circulations, impacts on the polar jet stream, impacts on climate around the world, impacts on weather in Australia.”

This collaborative global effort is crucial, as Dr. Humphries pointed out: “From an environmental perspective, the atmosphere is one atmosphere. It doesn’t care if you’re in Australia, or the US, or whatever, it’s all interconnected. We’re part of global monitoring networks, and we’re doing global climate models.”

Challenges and Future Prospects

For Ms. Bekemeier, the work is personal, especially as her role was funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), which has faced significant funding cuts. “I am really devastated to see what is happening to climate science and science in general in the United States and the gutting of the US Antarctic program,” she expressed. “I’m grateful that we have colleagues that can continue this work because we might not be able to do it in our own country.”

The research in the Southern Ocean holds the potential to unlock significant advancements in climate science, providing critical data to refine models and better predict future climate scenarios. As scientists continue to explore this remote frontier, their findings will be instrumental in shaping our understanding of global climate dynamics and informing policy decisions worldwide.