In a significant development in child welfare, the rate of out-of-home care for children in Finland has doubled over the past three decades. This trend, observed from 1993 to 2020, highlights a complex array of factors influencing child welfare interventions in the country. Researchers Aapo Hiilamo and Mikko Myrskylä from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR), alongside colleagues from the University of Helsinki, have delved into these trends using innovative demographic methods.

Out-of-home care, considered a last resort in child welfare, involves removing a child from their home to safeguard their well-being. The reasons for such placements are multifaceted, often involving scenarios of abuse, neglect, or mental health challenges faced by either the parents or the children themselves. The study published in the journal Child Abuse & Neglect offers a comprehensive view of these developments.

New Metrics Offer a Nuanced View of Child Welfare

Traditional metrics for monitoring out-of-home care typically count the number of children living outside their parental homes at a specific time. However, these figures can be misleading, as they fail to consider age structure differences, the duration and stability of care, or the potential for family reunification. Hiilamo, the study’s lead author, emphasizes the importance of addressing these complexities.

“Trends in out-of-home care are usually monitored by counting the number of children living outside their parents’ home at a given point in time. However, these metrics can be misleading because they don’t account for differences in age structure or important aspects such as the duration or stability of care, or the possibility of family reunification. We aimed to address these challenges,” explains Hiilamo.

The researchers tracked the daily living arrangements of all children in Finland throughout their childhood, calculating their probabilities of entering and exiting out-of-home care by age and year. This approach allowed them to calculate several nuanced metrics for each year from 1993 to 2020, including the proportion of children experiencing at least one out-of-home care episode, the expected duration of care, and the likelihood of returning to their family.

Rising Trends in Finland Raise Questions

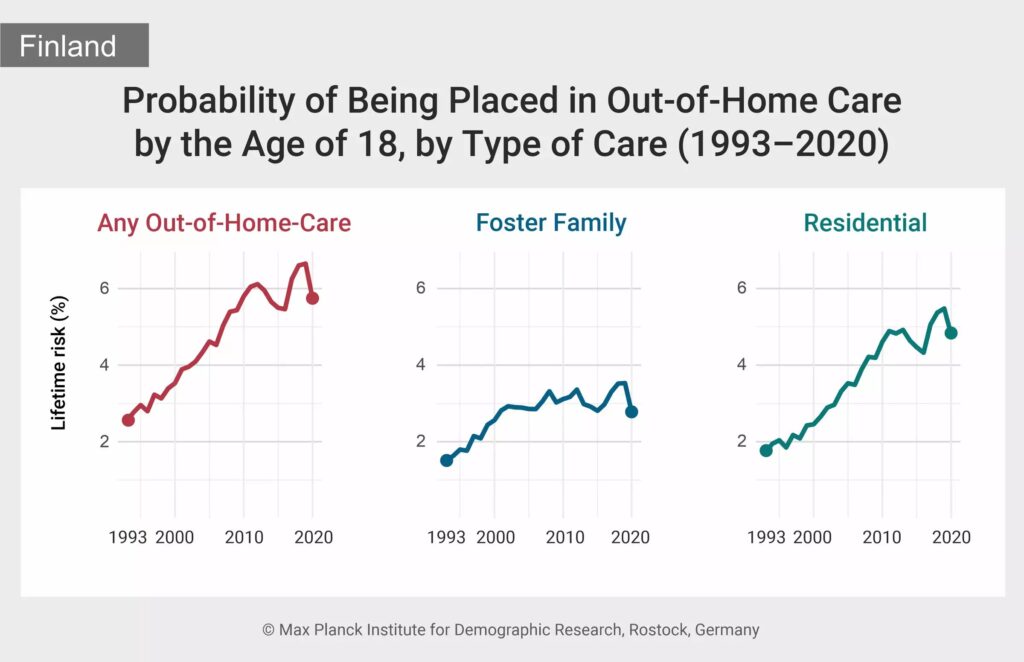

According to the study, about 6% of Finnish children are expected to be placed in out-of-family care at least once during their childhood under the conditions observed in 2020. This marks a twofold increase since 1993, primarily driven by a rise in residential care placements. Despite the increased risk of placement, the expected duration of care has decreased from 4.2 years in the early 1990s to 3.5 years in 2020. Additionally, the probability of a sustained return home by age 18 has increased from 32% to 44%.

“The rise in out-of-home care in general and in residential care in particular is both concerning and puzzling. Known risk factors, such as juvenile delinquency and alcohol consumption, have not changed in parallel, and similar trends are not seen across other Nordic countries. Further research is needed to understand why Finland has such high rates of out-of-home placements,” explains Hiilamo.

These findings raise important questions about the underlying causes of these trends in Finland. The increase in out-of-home care, particularly in residential settings, is not mirrored in other Nordic countries, suggesting unique national factors at play.

Demographic Methods Offer New Insights for Child Welfare Research

The study’s use of multistate models provides a valuable tool for understanding child welfare dynamics. These models can be adapted for use in other countries and areas of child welfare, such as studying transitions between referrals to child and youth welfare services and the interventions provided.

“Demographic research often focused on older populations due to aging societies, but these methods are equally valuable to studying children and youth. Demographic tools help quantify differences in child and youth welfare services across time and space, and thanks to new software developed at the MPIDR, these tools are now more accessible,” concludes Hiilamo.

As Finland grapples with the implications of these findings, the study’s methodology offers a blueprint for other nations seeking to understand and improve their child welfare systems. By providing a more nuanced picture of out-of-home care, policymakers can better address the needs and challenges faced by vulnerable children and their families.