In the presence of a tightly rolled, yellowed scroll at the State Library of Victoria, one cannot help but feel a sense of awe. Nestled inside a glass cabinet at the heart of the library is the oldest known mass-printed text in the world, the Hyakumantō Darani. This finger-length Buddhist prayer scroll circulated more than 700 years before the invention of the Gutenberg press.

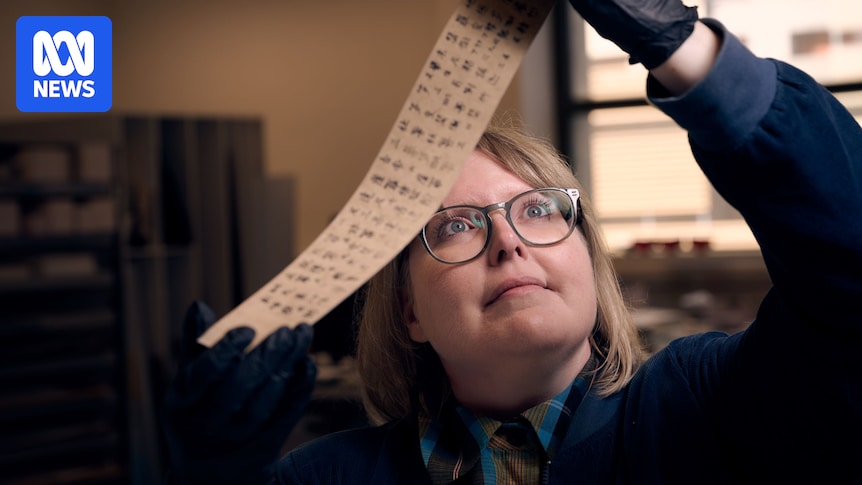

The Hyakumantō Darani, which translates to “1 million pagodas and Dharani prayers,” is a 1,300-year-old Buddhist Sanskrit text originating in India and printed in Japan using Chinese characters. Dr. Anna Welch, the principal curator at the library, explains that this ancient scroll is a surviving example of what were believed to be 1 million woodblock-printed scrolls and mini wooden pagodas commissioned by Japanese Empress Shōtoku in 764 to be sent to Japan’s ten major temples. It serves as the centerpiece of the library’s 20th anniversary World of the Book exhibition.

The flat version of the scroll on display is a facsimile, yet Dr. Welch recounts the emotional experience of witnessing the original being unfurled. “It was extremely moving,” she says. “We all held our breath. What a privilege to be around something that tells us the beginnings of the story of printed text and has survived 1,300 years.”

Oldest Surviving Literature

The World of the Book exhibition showcases a global history that spans 4,000 years of technological development in recorded writing. Among the treasures is the oldest object in the library’s collection: a 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablet from Southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq), which serves as a proto-tax receipt.

“It’s the script that’s used to record the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is the oldest surviving work of literature in the world,” Dr. Welch says.

New to the library’s collection and displayed for the first time is a medieval scribe’s knife, believed to have been made in Germany or the Netherlands in the 15th century. This tool was used to hold down vellum, a post-papyrus parchment invented by the Romans and made of animal skin, while writing with a quill and ink. It also served as a correction tool, akin to a historical form of white-out.

Accompanying these artifacts is the oldest book in Australia, De Institutione Musica (Principles of Music), dated at 1100 AD. The exhibition aims to make visitors consider the materiality of books and their cultural significance. “Not just what’s in the book, but how is it made? What does its form tell us about its cultural context, its meaning, and about our own assumptions of it?” Dr. Welch ponders.

From Hokusai to Astro Boy

The Hyakumantō Darani inspired a section of the exhibition that explores cross-cultural connections and the influence of Japan on the West, particularly after the 17th century. This mini-exhibition highlights the pre-Gutenberg history of mass printing and the artistry of Japanese woodblock prints, featuring works from Hokusai to Kawanabe Kyōsai.

Visitors can see Japanese editions of popular Western books and Westernized versions of Japanese art, reflecting a cultural exchange akin to peering through Alice’s looking glass. A manga version of Les Misérables sits next to an English translation of Astro Boy, alongside a series of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles books.

The World of the Book exhibition spans one of the upper galleries of the State Library’s domed reading room, showcasing over 300 works from its collection across five thematic areas. Highlights include a 1688 edition of the first science fiction novel by a woman, The Blazing World by Margaret Cavendish, and illustrated editions of Oscar Wilde’s novels by Aubrey Beardsley and André Derain.

Preserving History Through Innovation

The exhibition features a diverse range of printing and book manufacturing technologies, most of which require careful protection from light exposure. One noteworthy exception is a large codex art book by Lebanese Australian artist Deanna Hitti, featuring a woman hidden in a wash of blue. “This is a cyanotype,” Dr. Welch explains. “It’s a non-camera form of photography that was developed in the 19th century. What’s amazing about cyanotypes is that they’re light-sensitive. When you display them, they fade quickly, but if you close the book, it recharges.”

Dr. Welch imagines these ancient books communicating with each other after dark, reminiscent of the film Night at the Museum. “Oh, they have lives,” she says. “They absolutely have lives, these books. They’re like magic books to me. There’s an intangible quality to them that transcends their material form, but comes from it. It is a kind of time machine.”

The World of the Book exhibition is free and will run at the State Library of Victoria until May 17, 2026, offering a unique opportunity to explore the rich tapestry of human history through the lens of written texts.