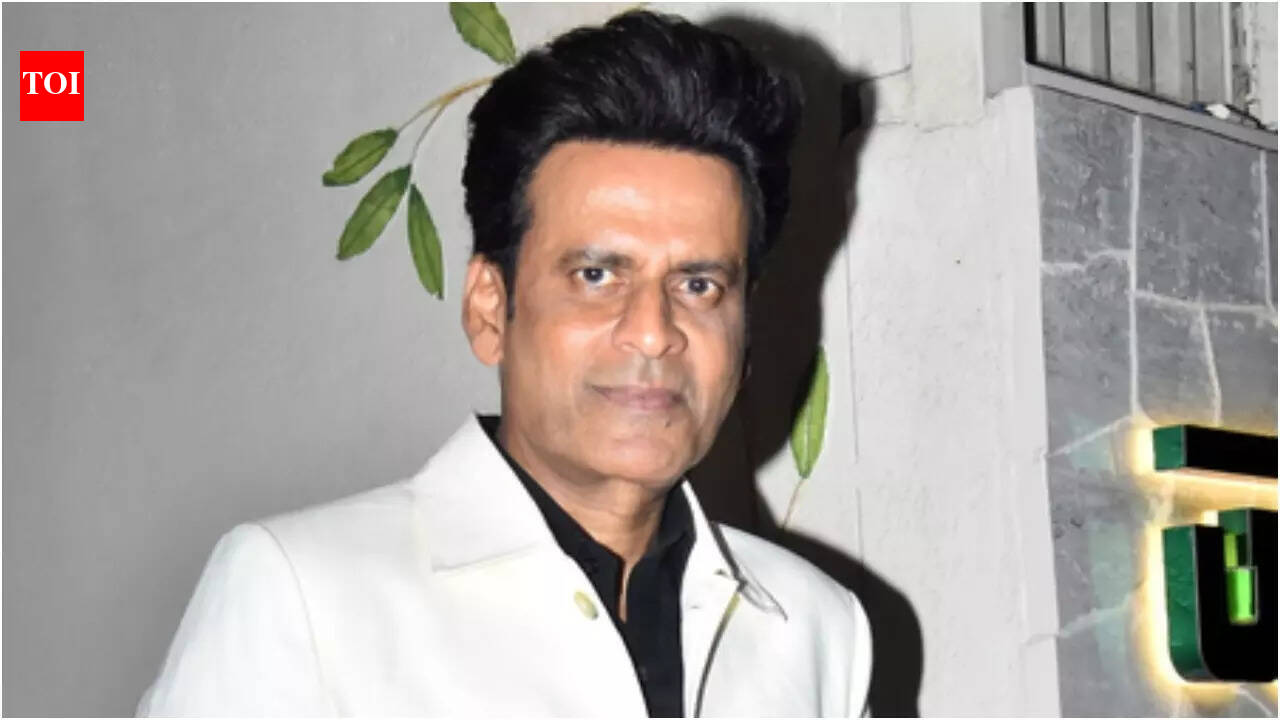

Retired businessman Alan Hall gazes out from the floor-to-ceiling glass of his sleek Melbourne apartment at the glorious panorama of the city skyline before him, but his cheery countenance crumples into a frown. By rights, he should now be enjoying the best days of a new cashed-up, carefree chapter of his life, spending all his time on family, friends, and fun. At least that’s what he imagined downsizing from a large, labor-intensive family house in the suburbs to a smaller Docklands unit would mean for him. But it hasn’t quite worked out that way.

“Whenever I work from home, I can look at all of the city through the window, and it’s beautiful,” he says. “We love the views and do like this apartment and the kind of lifestyle it affords us, but…” He pauses to consider his words. “The whole downsizing experience hasn’t been as smooth or as enjoyable as we’d hoped. Moving from a large home to here was a big decision, and it took my wife considerable time to come on board. But it’s been soured by a lot of things that happened along the way.”

Unexpected Challenges in Downsizing

Hall, 68, and his wife Susan Shaw, 59, sold their two-storey, four-bedroom family house in Williamstown in Melbourne’s south-west in 2020 to move into a two-bedroom apartment they bought off the plan as a way of shrinking their real estate footprint and spending less time on mowing lawns and home maintenance. He ended up, however, ploughing even more time in trying to sort out some of the issues that absolutely confounded him about his new home, which they moved into in 2021 following delays in construction.

“I just wasn’t expecting things like defects that seem to be very slow to be rectified,” says Hall, who, after a stellar career in sales, was hardly naïve in his expectations. He sighs in exasperation. “There’s been flooding that’s been so bad, the guy in the apartment down the corridor to us had to vacate his apartment on at least two occasions, while I still have a problem with one of my external windows. Then there was the discovery that to get access to the gym and pool in the building, you have to pay extra. We weren’t aware of that; nobody mentions you have to pay over and above the price of the property.”

Government Incentives and the Reality of Downsizing

State governments across Australia are all busily trying to persuade empty nesters to free up their big family houses for the next generation and move into apartments or smaller town homes, terraces, and villas to make space for higher-density developments. The Australian Taxation Office offers generous superannuation concessions to sweeten the deal, while there are also stamp duty concessions available, at times, for buying off the plan. Politicians, developers, and real estate agents alike regularly portray downsizing as the delectable lifestyle dream.

“Think no lawns to mow, no jobs around the house every weekend, the chance to pay off the mortgage with cash left over after the new purchase, better security, and usually living closer to cities in all their magnificent amenity.”

Yet more and more Baby Boomers are discovering it’s not a generational shift that suits everyone. Yes, there’s all the time and money it can free up, but there’s also a full package of potential negatives that can turn a transfer to a smaller home into a claustrophobic nightmare, or a move into a luxury high-rise into pie-in-the-sky. And when downsizing doesn’t play out as planned, there’s a darker underbelly of festering fury and regret.

Personal Stories of Downsizing Woes

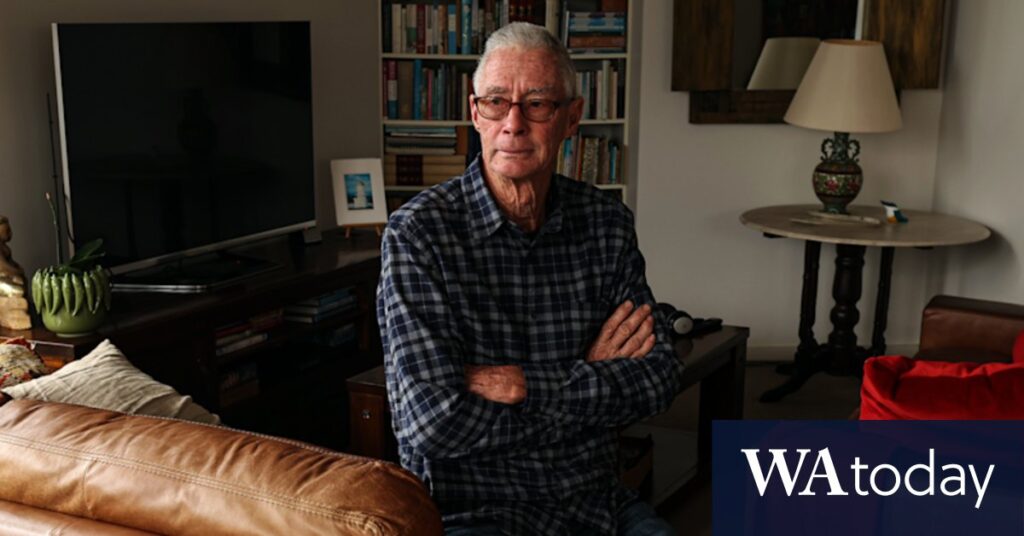

In Sydney, retired high school teacher Peter Moor moved from a spacious two-level house on a large block in Chatswood on the north shore to a two-bedroom apartment in Neutral Bay, closer to the harbour. A tall, craggy, silver-haired 78-year-old with a brisk, businesslike manner, he pulls no punches either in his assessment of his downsize. “It’s an absolute frigging nightmare,” he says. “I downsized from a nice four-bedroom house on a very nice block into a two-bedroom apartment and it’s been a disaster. It’s the worst decision I ever made, and I feel quite embittered about it all.”

Meanwhile, former surgical nurse Felicity Jacobs, who downsized further away from the city, also feels she acted in haste and is repenting at leisure. She has a faraway look in her pale blue eyes as she recalls her last home in Sydney’s inner west, in lively, multicultural Enmore. There, she lived a full life meeting up with friends of all ages, eating at the area’s diverse restaurants, and attending art and cultural events. Now, she has a smaller, cheaper villa in a retirement village in Bathurst, in the NSW Central Tablelands.

“But I hadn’t really thought about how much I might miss my old community,” says Jacobs, 72, pushing her fashionable white bob behind her ears in irritation. “I hardly know anyone here, and have to drive a long way all the time to see my old friends, or they have to travel to see me.” She purses her lips. “I know it sounds bad, but it’s all old people living here, and it’s stressful hearing about their medical problems, and seeing them not doing so well. It’s not like living in a normal community where you have people of all ages and interests, and kids around.”

Research and Statistics on Downsizing

The last major survey to sample downsizing trends was done in 2020 by Curtin University and Swinburne University of Technology, when there were around 6.5 million Australians aged 55 or over. It suggested that downsizing could be relevant to 2.5 million of their 4.3 million households. When 2400 households were questioned in 2018, 26 per cent had already downsized and another third had thought about it. Overall, the findings pointed to a strong appetite among older Australians to downsize their dwellings, concluded the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

“In addition, the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR) estimated that around 36 per cent of homeowners still had a mortgage when they retired in 2016, up from 23 per cent a decade prior.”

Downsizing, it suggests, could extinguish remaining debt, free up money for holidays, restaurants, and the good life, and enable a move to a more age-friendly, single-level home or apartment. A 2019 CEPAR working paper with Sydney’s Macquarie University and the University of NSW found, however, that of 352 55-plus participants in an online survey who’d downsized over the preceding five years, one in six expressed regret about moving.

There are certainly downsides to downsizing. People may feel a strong emotional attachment to the houses where they brought up their children, and might find it hard to declutter and then confine their lives – and guests – to smaller spaces. Older Boomers may find it hard to overcome feelings of dislocation and loss. Others can be shocked by the discovery that apartments, especially new ones, can be just as expensive as the houses they sell.

Conclusion: The Complex Reality of Downsizing

Alan Hall, with the jovial demeanour of an assistant football coach who shares in all the team’s successes but can shrug off its failures, agrees. Yet it’s not always possible to remain so easy-going. “Probably one of the best things about downsizing is becoming mortgage-free,” he says. “That’s a big landmark in your life. But then you have to realise you pay levies. We pay $10,000 to $12,000 a year, which can be just like paying a mortgage.”

For some, downsizing is nothing like the nirvana they hoped for. Peter Moor, clad in a check shirt and blue jeans, perches on the end of a chair at the dining table in his Neutral Bay penthouse he shares with his wife, and his face darkens behind his tortoiseshell glasses. Fit and active, he once did all his own maintenance on their old house, but that’s obviously not an option with an apartment. And while there are plenty of things he likes about where he now lives, there are many more he does not.

“We do have a nice private apartment, and it has shops and 100 restaurants within walking distance, and it’s low maintenance,” he says. “But we have four strata schemes here with residential and retail, with an overarching building management committee, and we pay so much in strata levies. I led a coup on the committee because there was such a lack of oversight over contracts and quotes and spending, and I’ve been on a relentless crusade ever since to reduce costs.”

The thing that galls Moor most, however, is that he’s horrified by how much his old house has increased in value, while his apartment has appreciated barely at all. “From a financial point of view, it’s absolutely disastrous,” he says. “If I’d have kept that lovely house on a beautiful block with a big workshop and garage, I’d be sitting on a goldmine.”

Often those who are clouded by such regret over downsizing go under the radar. A number of people approached by Good Weekend admitted they wished they’d never moved from their comfortable houses into smaller homes or strata, but declined to comment on the record as they didn’t want to be seen as having made what they now feel is a bad decision, and are trying to make the best of things.

This was set to be their forever home and it can be excruciating to mourn the move and lament what they’ve lost. Ellen, 65, for example, agreed to speak on condition her real name wasn’t used. She has been in a painful limbo for the last 18 months. Deciding to leave her big house after she split with her husband and their two adult children left home, she took out a contract for a much smaller home to be built within the same Brisbane outer suburb. But delays from bad weather have plagued the build.

“I am absolutely trapped now, with a house that’s not finished and another one that’s costing me a fortune,” she says, her voice thick with emotion. “It’s draining my savings and I’m drawing down on my pension and the builders seem in no rush at all to finish it. Who knows where this will end? I dearly wish I’d never even started.”

Sydney real estate agent Ben Collier of The Agency is familiar with downsizer distress. “You sometimes come across people downsizing too far,” he says. “Then they sell and come back to the market to upsize to somewhere bigger. Or I have seen people downsize to apartments and not enjoy the body corporate experience. Then they’ll buy again to move into a terrace house. They want the apartment lifestyle but don’t want to live in an apartment.”

Even villas can be problematic, as Felicity Jacobs, an energetic, sprightly retiree who spends a lot of her time ferrying around neighbours to medical appointments, attests. “I just miss the diversity of having people from all over the world, and of all ages and interests,” she says. “It was so multicultural and a really creative community I came from.”