What if you could create new materials just by shining a light at them? This concept, which might sound like science fiction or alchemy, is the ambitious goal of physicists delving into the burgeoning field of Floquet engineering. By using a periodic drive such as light, scientists can “dress up” the electronic structure of any material, altering its fundamental properties—potentially transforming a simple semiconductor into a superconductor.

While the theory of Floquet physics has been investigated since a bold proposal by Oka and Aoki in 2009, only a handful of experiments over the past decade have demonstrated Floquet effects. These experiments have shown the feasibility of Floquet engineering, but the field has been constrained by its reliance on light, which requires very high intensities that almost vaporize the material while achieving only moderate results.

Now, a diverse team of researchers from around the world, co-led by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) and Stanford University, has demonstrated a powerful new approach to Floquet engineering. By showing that excitons can produce Floquet effects much more efficiently than light, their results, published in Nature Physics, mark a significant advancement. “Excitons couple much stronger to the material than photons due to the strong Coulomb interaction, particularly in 2D materials,” says Professor Keshav Dani from the Femtosecond Spectroscopy Unit at OIST. “They can achieve strong Floquet effects while avoiding the challenges posed by light. With this, we have a new potential pathway to the exotic future quantum devices and materials that Floquet engineering promises.”

Dressing Up Quantum Materials with Floquet Engineering

Floquet engineering has long been considered a path towards creating on-demand quantum materials from regular semiconductors. The principle underlying Floquet physics is relatively straightforward: when a system is subjected to a periodic drive—a repeating external force, like a pendulum—the overall behavior of the system can be richer than the simple repetitions of the drive. Think of a playground swing: periodically pushing the person lifts the swing to greater heights, even though the swing itself oscillates back and forth.

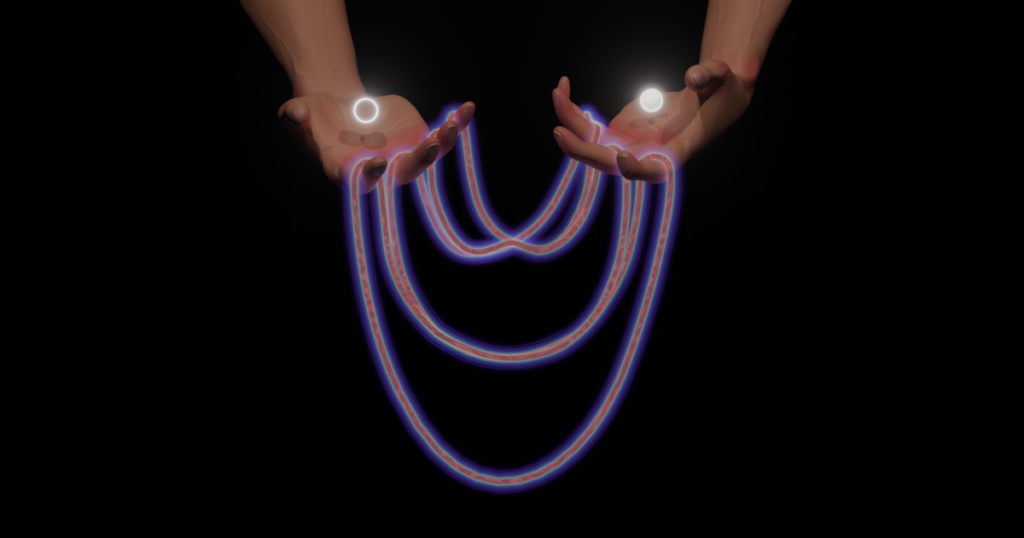

Floquet engineering applies this principle to the quantum world, where the lines between time and space are blurred. In crystals, such as semiconductors, electrons are already subject to one periodic potential—periodic not in time, but space; the atoms are locked in a tight lattice formation, confining the electrons to a specific energy level, or band, as dictated by the specific periodic atomic structure. When light is shone at the crystal at a set frequency, a second periodic drive is introduced—now in time, as the electromagnetic photons interact rhythmically with the electrons—shifting the permitted energy bands of the electrons.

By tuning the frequency and intensity of the periodic light drive, the electrons can be made to inhabit new, hybrid bands, in turn altering the electron behavior of the entire system and thus the properties of the material—like how two musical notes harmonize to form a new, third note. As soon as the light drive is turned off, the hybridization ends, and the electrons swing back into the energy bands permitted by the crystal structure. For the duration of the “song,” researchers can “dress up” materials to exhibit entirely novel behaviors.

Excitons: A New Frontier in Floquet Engineering

“Until now, Floquet engineering has been synonymous with light drives,” says Xing Zhu, a PhD student at OIST. “But while these systems have been instrumental in proving the existence of Floquet effects, light couples weakly to matter, meaning that very high frequencies, often at the femtosecond scale, are required to achieve hybridization. Such high energy levels tend to vaporize the material, and the effects are very short-lived. By contrast, excitonic Floquet engineering requires much lower intensities.”

Excitons form in semiconductors when individual electrons are excited from their “resting” state (the valence band) to a higher energy level (the conduction band), usually by photons. The negatively charged electron leaves behind a positively charged hole in the valence band, and the electron-hole pair forms a bosonic quasiparticle that lasts until the electron eventually drops back into the valence band, emitting light.

“Excitons carry self-oscillating energy, imparted by the initial excitation, which impacts the surrounding electrons in the material at tunable frequencies. Because the excitons are created from the electrons of the material itself, they couple much more strongly with the material than light. And crucially, it takes significantly less light to create a population of excitons dense enough to serve as an effective periodic drive for hybridization—which is what we have now observed,” explains co-author Professor Gianluca Stefanucci of the University of Rome Tor Vergata.

Lowering the Bar with World-Class TR-ARPES Setup

This breakthrough is the culmination of the OIST unit’s history of exciton research and the world-class TR-ARPES (time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy) setup they have built in tandem. To investigate excitonic Floquet effects, the team excited an atomically thin semiconductor with an optical (i.e., light) drive and recorded the energy levels of the electrons.

First, they used a strong optical drive to directly observe the Floquet effect on the electronic band structure, itself an important achievement. Next, they dialed the optical drive down by more than an order of magnitude and measured the electron signal 200 femtoseconds later to capture the excitonic Floquet effects separately from the optical. “The experiments spoke for themselves,” says Dr. Vivek Pareek, an OIST graduate who is now a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow at the California Institute of Technology. “It took us tens of hours of data acquisition to observe Floquet replicas with light, but only around two to achieve excitonic Floquet—and with a much stronger effect.”

With this, the multidisciplinary team has conclusively proven that not only are Floquet effects achievable in general and not only with light, but that these effects can be reliably generated with other bosons than just photons, which have dominated the field until now. Excitonic Floquet engineering is significantly less energetic than optical, and theoretically, the same effect should be achievable with other “ons” created through a broad palette of excitation—like phonons (using acoustic vibration), plasmons (using free-floating electrons), magnons (using magnetic fields), and others.

As such, the researchers have laid the foundation for practical Floquet engineering, which holds great promise for the reliable creation of novel quantum materials and devices. “We’ve opened the gates to applied Floquet physics,” concludes study co-first author Dr. David Bacon, a former OIST researcher now at University College London, “to a wide variety of bosons. This is very exciting, given its strong potential for creating and directly manipulating quantum materials. We don’t have the recipe for this just yet—but we now have the spectral signature necessary for the first, practical steps.”