Antibiotic treatments are increasingly losing their effectiveness against a range of common bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella, and Acinetobacter. This alarming trend was highlighted in a warning issued by the World Health Organization last October. In a promising development, researchers from Penn State and The University of Minnesota Medical School have discovered a potential solution for tuberculosis by chemically altering the structure of naturally occurring peptides to create a more stable and effective antimicrobial agent.

Their groundbreaking research, published in Nature Communications, suggests that these synthetically structured peptides could enhance the efficacy of current tuberculosis drug regimens. “There’s a desire to create new drugs that can kill bacteria through mechanisms that are not used by traditional antibiotics,” explained Scott Medina, Korb Early Career Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Penn State and the study’s corresponding author.

Challenges with Traditional Antibiotics

Traditional antibiotics typically work by targeting specific biochemical pathways in bacteria. However, these pathways are prone to resistance mutations, which bacteria evolve to evade the antibiotics. The researchers aimed to overcome this challenge by focusing on host-defense peptides (HDPs), short chains of amino acids naturally produced in the body, known for their potential in treating antibiotic-resistant infections. Unfortunately, these peptides are often unstable and quickly degraded by enzymes in the body.

To address this instability, the research team employed chemical techniques such as “backbone-inversion,” which reverses the structural framework of the peptide, and chirality switching, which alters the molecule’s spatial orientation. These modifications aimed to enhance the peptide’s resilience against enzymatic degradation.

Breakthrough in Peptide Stability and Potency

The researchers discovered that the retro-inverted variant of the peptide was not only more stable but also significantly more potent against the tuberculosis pathogen. “When we compared the original molecule to the modified one, we found that the modified peptide was not only more stable but also much more active,” Medina noted.

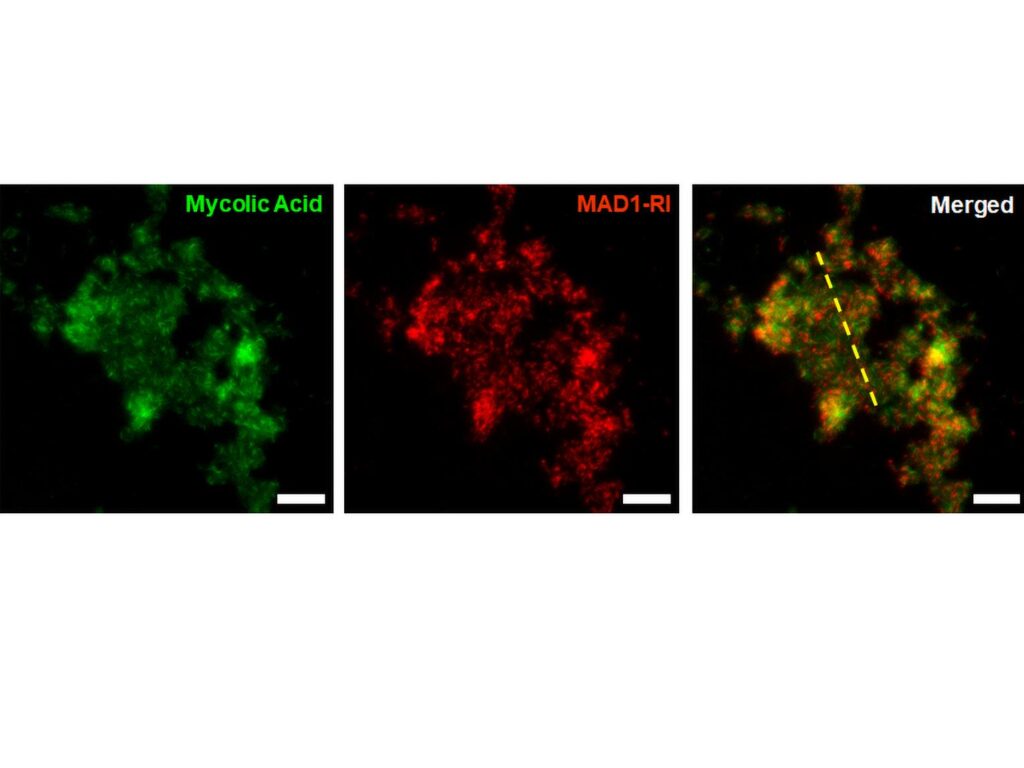

Using advanced microscopy and structural analysis techniques, the team identified that the new shape imparted by the retro-inversion made it more energetically efficient for HDPs to penetrate bacterial cell membranes. This mechanism differs from traditional antibiotics, as the inverted HDPs physically degrade the membrane, making it more challenging for bacteria to evolve resistance.

Implications for Tuberculosis Treatment

Medina emphasized that while this discovery is promising, it is not intended to replace existing tuberculosis therapies. “We don’t envision that this is a drug that’s going to entirely replace current TB therapies. Rather, we think the biggest value of our molecule is its potential to enhance the activity of current TB drugs when given together, making the current treatments much more effective,” he said.

The research team included Sabiha Sultana, Diptomit Biswas, and Neela Yennawar from Penn State, along with Hugh Glossop, now at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. From the University of Minnesota Medical School, the team included Gebremichal Gebretsadik, Nathan Schacht, Muzafar Ahmad Rather, and Anthony Baugh. The project received funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Future Directions and Broader Impact

This development follows a growing trend in biomedical research focusing on alternative antimicrobial strategies. The potential for these modified peptides extends beyond tuberculosis, offering hope for combating other antibiotic-resistant infections. As antibiotic resistance continues to rise, the need for innovative solutions becomes ever more pressing.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest public health challenges of our time, with at least 2.8 million people in the United States acquiring antibiotic-resistant infections annually. The work by Medina and his team represents a significant step forward in addressing this global health crisis.

Moving forward, further research and clinical trials will be necessary to fully understand the potential of these modified peptides in real-world applications. However, the initial findings provide a promising glimpse into a future where antibiotic resistance could be effectively managed, potentially saving millions of lives worldwide.