The Nipah virus has recently re-entered the global spotlight following an outbreak in India, raising concerns about its potential spread. Although the virus is not currently present in Australia, it continues to cause small but serious outbreaks in other parts of the world. Researchers at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) are actively studying the Nipah virus and related bat-borne pathogens to bolster national preparedness and enhance scientific understanding of emerging pathogen threats.

Earlier this year, CSIRO announced the discovery of a previously unknown virus in the same family as the Nipah virus, further emphasizing Australia’s ongoing research focus on high-consequence pathogens. Dr. Sarah Edwards and Ms. Jenn Barr from CSIRO provide insights into what we know about Nipah, its transmission pathways, and how Australian science is contributing to global efforts to monitor and understand emerging viruses.

Understanding the Nipah Virus

Dr. Sarah Edwards, Group Leader of Zoonotic Pathogens and Models at CSIRO, describes the Nipah virus as a highly pathogenic zoonotic virus, meaning it spreads from animals to humans. It can cause severe respiratory illness and fatal brain inflammation, clinically known as encephalitis. First identified in 1998, Nipah is considered one of the most dangerous emerging infectious diseases due to its high fatality rate and the absence of approved treatments or vaccines.

While the Nipah virus is not currently found in Australia, closely related viruses such as the Hendra virus, carried by Australian flying foxes, are present. The Hendra virus can spill over from bats to horses, and infected horses can then transmit the virus to humans. However, there is no evidence of direct transmission of the Hendra virus from bats to humans.

Recent Outbreaks and Transmission

Current Outbreak in India

According to Dr. Edwards, Nipah virus outbreaks occur almost annually in parts of Asia, particularly in India and Bangladesh. The current outbreak in India is not caused by a new strain of the virus, but it is occurring in West Bengal, an area that has not seen cases of Nipah virus for nearly 20 years.

Differences Between Outbreaks in Bangladesh and India

Dr. Edwards explains that while the viruses reported in Bangladesh and India are closely related, they are not identical. The main difference lies in how spillover occurs. In Bangladesh, cases are often seasonal and linked to the consumption of contaminated sap from date palms. In India, outbreaks are usually linked to healthcare settings or exposure to bats. Despite these differences, both regions experience severe disease and high fatality rates during outbreaks.

Transmission Pathways

Ms. Jenn Barr, an experimental scientist and leader of the Pathogen Investigation team at CSIRO, outlines the transmission pathways of the Nipah virus. Animal-to-human transmission can occur when people come into direct contact with infectious bodily secretions of fruit bats or infected intermediate hosts like pigs. Contaminated food, particularly date palm sap, also plays a significant role in transmission. The virus can spread from person-to-person through close contact with an infected individual or exposure to their bodily fluids.

Impact on Australia and Research Initiatives

Potential Impact on Australia

Ms. Barr assures that there have been no recorded outbreaks of the Nipah virus in Australia to date. It is highly unlikely that animals or people in Australia will be affected by the current outbreak, as the virus does not spread easily between people and requires close, prolonged contact with infected individuals.

Nipah virus is extremely rare, with isolated outbreaks occurring almost exclusively in Bangladesh and India. Despite its high fatality rate and significance as an unpredictable outbreak threat, Nipah virus spreads poorly between people and lacks airborne transmission.

CSIRO’s Research Efforts

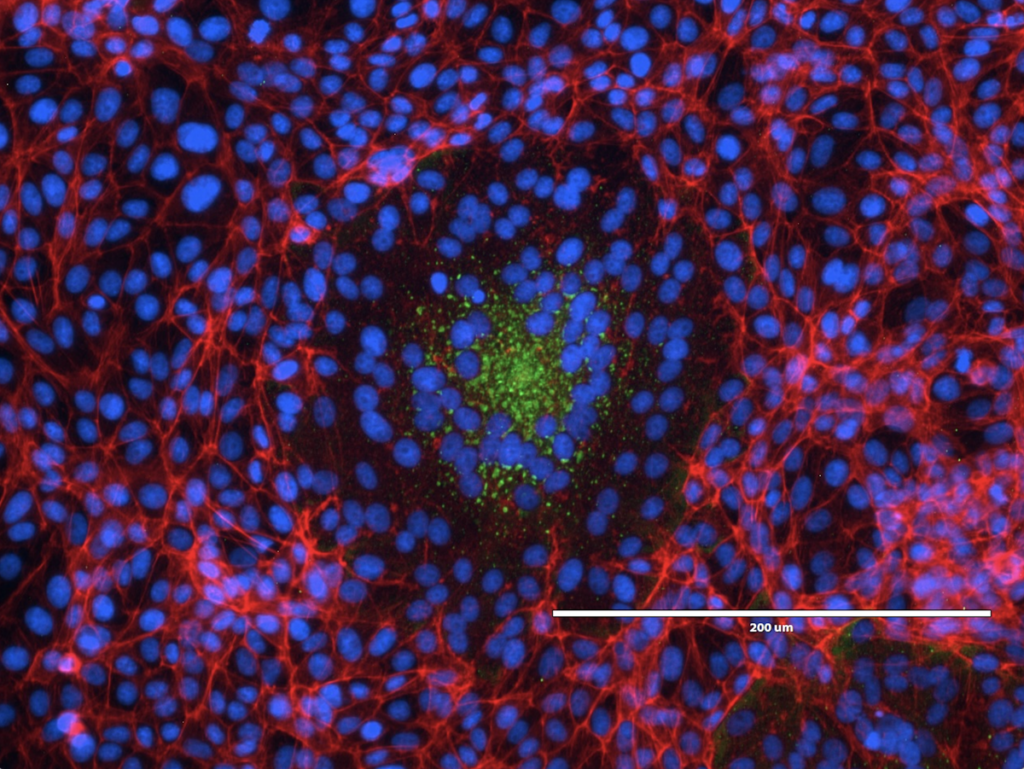

Dr. Edwards highlights that CSIRO’s Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (ACDP) has been focusing on Nipah virus research since the initial outbreak in 1998. The research encompasses various areas, including the development of diagnostic tests for early detection, understanding the virus’s behavior, and conducting early-stage studies to evaluate potential vaccines and therapeutics. Additionally, CSIRO engages in field surveillance both domestically and internationally.

Safe Study of Viruses

All work with the Nipah virus is conducted in specialized infrastructure, a Biosafety Level 4 laboratory, which is the highest biosafety level globally. Pathogens requiring this level of containment cause severe or fatal disease and have no licensed vaccines or therapeutics available. Scientists at ACDP undergo extensive biosafety training and wear fully encapsulating suits when researching pathogens like Nipah and Hendra viruses.

The Role of Bats in Virus Transmission

Why Bats Host Many Viruses

Ms. Barr explains that bats do not necessarily carry more diseases than other animals, but some of the viruses they host can be especially harmful to humans. Spillover events are often driven by human activities. When natural habitats are reduced or disrupted, wildlife is forced into closer contact with people and livestock, increasing the risk of spillover. In contrast, healthy, intact ecosystems help buffer and reduce the emergence of new diseases.

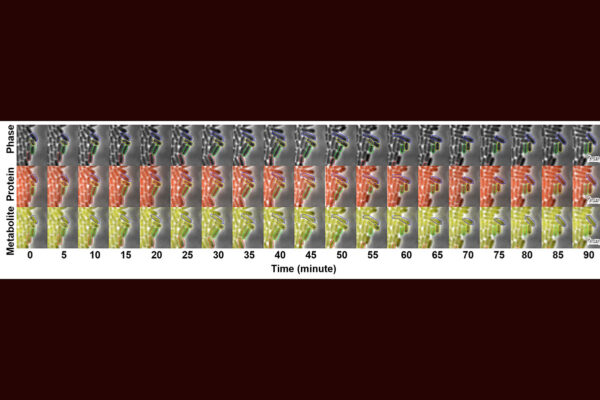

Bats’ Unique Immune Response

Bats have a unique immune response that prevents them from getting sick from viruses deadly to humans. Unlike humans, whose strong inflammatory response can cause illness, bats suppress biological pathways that would otherwise trigger damaging inflammation. CSIRO research has found that some components of the Australian flying fox immune system are already active before infection occurs, giving them an early advantage in defending against viruses.

Handling Sick or Trapped Bats

Ms. Barr advises that most viruses bats carry are unlikely to be transmitted directly to humans. However, it is important never to handle a bat due to the risk of Australian bat lyssavirus transmission through bites or scratches. If you encounter an injured or distressed bat, contact a wildlife rescue organization to arrange for a vaccinated and trained rescuer to assist.

The ongoing research and preparedness efforts by CSIRO and other global institutions are crucial in understanding and mitigating the risks posed by the Nipah virus and similar pathogens. As the world continues to grapple with emerging infectious diseases, scientific collaboration and vigilance remain key to safeguarding public health.