Your memory might seem unreliable when you forget the flavor of your last birthday cake or the plot of a recent movie. Yet, you might instantly recall the surface temperature of the Sun. This raises the question: Is your memory truly poor, or is it functioning just fine? Memory is central to our identity, but it reveals a surprising complexity upon closer examination.

Memory is not a singular entity; it comprises multiple types, each influencing how we remember facts about the world and ourselves. This article delves into the intricacies of memory, exploring its various forms and their impact on our sense of self.

Understanding Memory Classifications

Cognitive psychologists categorize memory into two primary types: declarative and non-declarative memory. Non-declarative memories, such as skills and habits like typing or cycling, occur without conscious recollection. In contrast, declarative memories involve conscious awareness, such as knowing your name or recalling that you put mustard in the fridge.

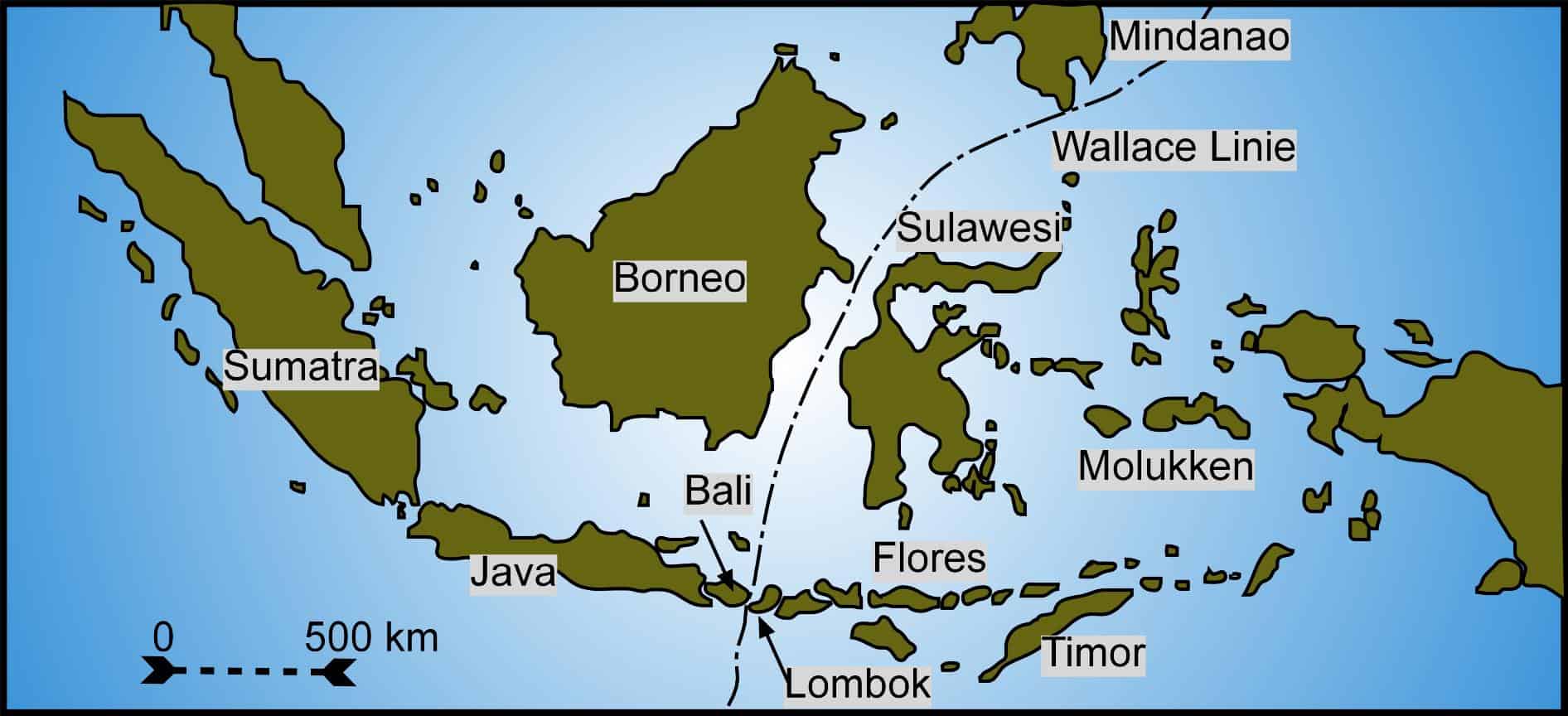

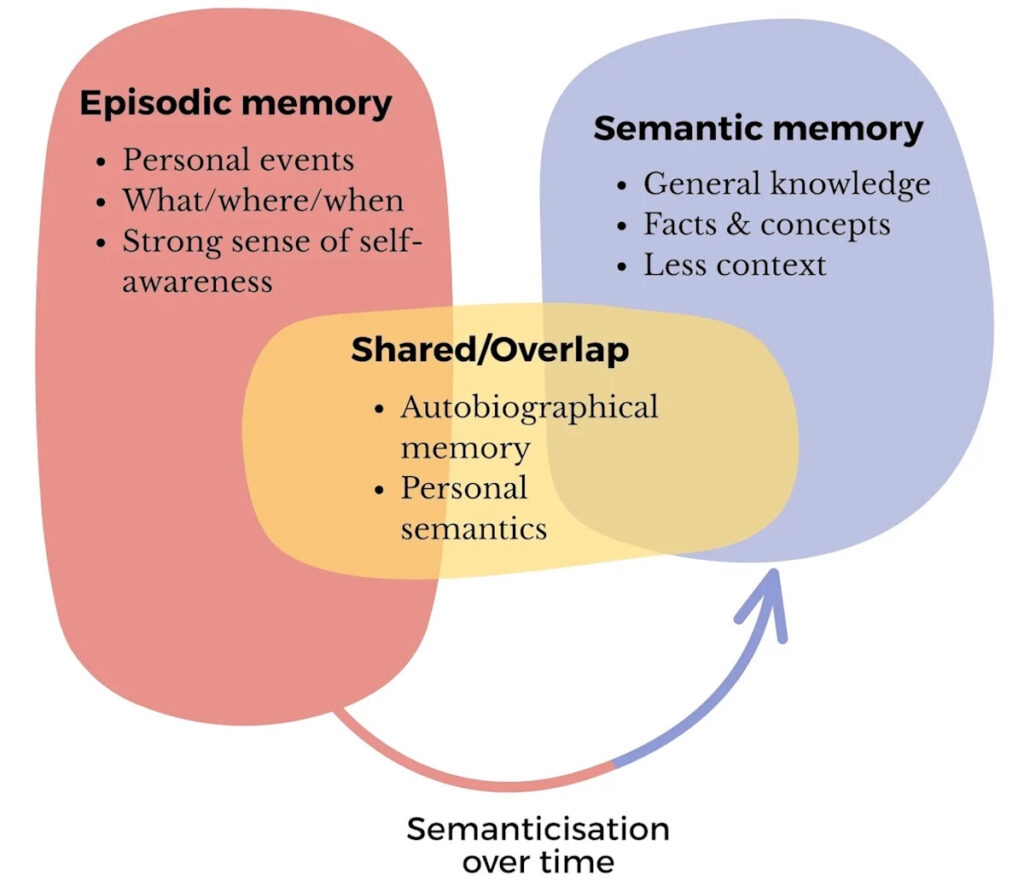

Declarative memory further divides into semantic and episodic memory. Semantic memory encompasses general knowledge, like knowing cats are mammals. Episodic memory involves personal life events, characterized by elements of “what,” “where,” and “when.” For instance, remembering cuddling a pet cat in your home office before writing an article.

The Role of Self-Awareness in Memory

A sense of self-awareness is intricately linked to episodic memory, offering the feeling of personally reliving experiences. In contrast, semantic memories often lack this personal context, as seen in knowing Canberra is Australia’s capital without recalling when you learned it.

Lessons from Amnesia

Mid-20th-century studies of amnesic patients highlighted the distinction between semantic and episodic memory. Patients like Henry Molaison and Kent Cochrane suffered brain damage, severely impairing their episodic memory while retaining general knowledge. Cochrane, for instance, could describe changing a flat tire in detail despite not remembering the experience.

Conversely, cases of semantic dementia exhibit impaired semantic memory with intact episodic recall, further illustrating the complexity of memory systems.

The Impact of Age on Memory

Memory systems develop and decline at varying rates throughout life. Young children develop semantic memory first, with episodic memory maturing around ages three to four, explaining scant early childhood memories. As we age, episodic memory declines faster than semantic memory, affecting older adults’ ability to recall specific events.

In severe cognitive decline, such as dementia, episodic memory suffers more than semantic memory. For example, an affected individual might forget yesterday’s lunch but retain knowledge of what pasta is.

The Interconnectedness of Memory Types

Brain imaging studies reveal overlapping brain areas active during both semantic and episodic memory recall, suggesting more similarities than differences. Some researchers propose viewing these memories as a continuum rather than distinct systems.

Autobiographical memory, or personal semantics, exemplifies the interplay between memory types. Declaring oneself a “good swimmer” may seem semantic, but it often evokes episodic memories of swimming experiences. This phenomenon, known as semanticisation, challenges the traditional distinction between memory types.

Ultimately, how we remember shapes how we understand ourselves. Episodic memory allows us to mentally return to experiences that feel personally lived, while semantic memory provides the stable knowledge that binds those experiences into a coherent life story.

Over time, the boundary between memory types softens, transforming specific events into broader beliefs about identity, values, and capabilities. Memory is not merely a repository of the past; it is an active system continuously reshaping our sense of self.

This article is republished from The Conversation and was written by Shane Rogers, Edith Cowan University.

Read more:

- What we get wrong about forgiveness – a counseling professor unpacks the difference between letting go and making up

- Comfort them or let them tough it out? How parents shape a child’s pain response

- Love, fear, anger and hope: how emotions influence climate action

Shane Rogers does not work for, consult, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.