A groundbreaking study from Dartmouth, published in Nature Communications, unveils a surprising mechanism by which immune cells in the brain, known as microglia, execute their rapid response missions. Upon reaching injury sites, these cells arrive with minimal resources, powered by what could be likened to the cellular equivalent of a candy bar. This lightweight approach allows them to act swiftly, while simultaneously preparing for sustained damage control by recruiting additional energy sources.

Microglia, the central nervous system’s primary immune cells, react to threats within minutes by extending arm-like projections to contain damage. “It’s like troops that are initially responding to some emergency with only a candy bar in their pocket,” explains Robert Hill, an associate professor of biological sciences and senior author of the study. “They only carry enough supplies to power that initial invasion, but to really resolve the damage, you need to build a road and pull in the mitochondria.”

Understanding Microglial Metabolism

The study reveals that these early-responding microglial arms lack mitochondria—the cell’s energy powerhouses. It takes approximately six hours for mitochondria to reach the site, as the cells must first construct pathways to transport them. This indicates that the microglia’s initial actions rely on glycolysis, a less efficient energy production method from sugar, or energy sourced elsewhere within the cell.

Given that microglial metabolism can become dysfunctional with age and neurodegenerative diseases, understanding how healthy microglia manage their energy needs is crucial. “This study establishes a foundation for understanding mitochondria and microglia in the healthy brain, and we’ll be referring back to it for a long time as we start investigating diseased contexts,” says Alicia Pietramale, who led the research as a Guarini Ph.D. candidate in Hill’s group.

The Role of Mitochondria in Microglial Function

Microglia are highly mobile, constantly patrolling the brain for pathogens and tissue damage. They are also adept shapeshifters, rapidly extending and retracting processes to explore their environment. When they detect damaged cells or debris, they engulf it through phagocytosis, effectively digesting the material.

These dynamic movements are energy-intensive, prompting Pietramale and Hill to examine the cell’s mitochondria to understand energy allocation. Previous research indicates that most cells have mitochondria dispersed throughout, though some strategically position them in high-energy demand areas. However, little was known about mitochondria in healthy microglia until now.

“Since microglia need energy to carry out a rapid response to traumatic insult, we expected their mitochondria to move with them,” Hill notes.

Mitochondrial Movement: A Delayed Response

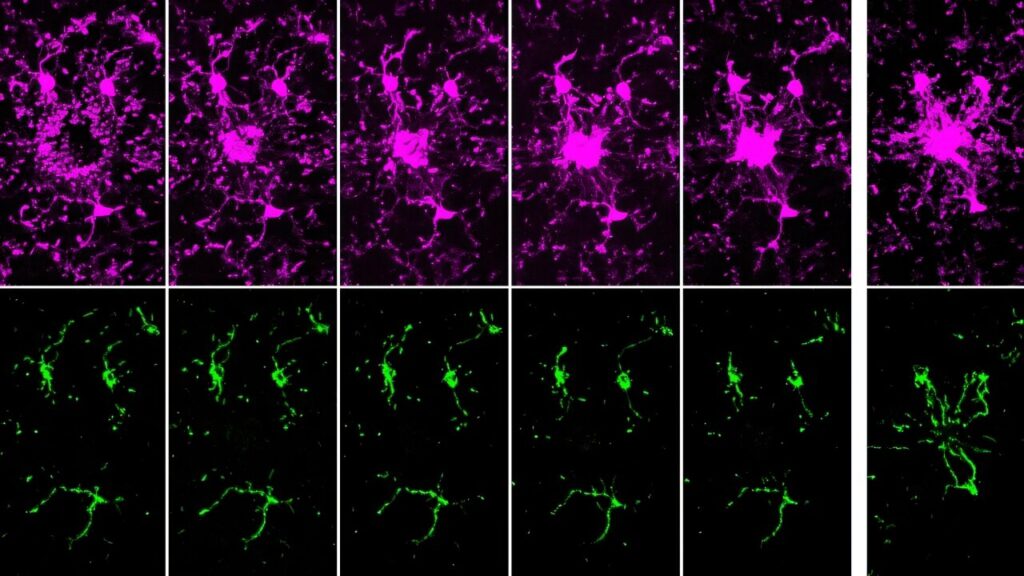

Using mice with fluorescently tagged microglia and mitochondria, researchers observed these cells in their natural environment. “What’s really powerful about our model is that we can study microglia in living brains,” Pietramale says. The study found that mitochondria are not evenly distributed within microglia. Some processes contained many mitochondria, while others had none, and more active processes had fewer mitochondria than less active ones.

This uneven distribution suggests microglia optimize energy use by not transporting mitochondria to fleeting processes. “Why spend the energy transporting mitochondria to all parts of microglia when some of these processes only reside in a position for as little as a minute?” Pietramale explains.

Filming microglia’s response to brain cell damage revealed that initial responders lacked mitochondria for hours post-injury. Mitochondria began to appear three hours later, fully arriving six hours after the injury. This movement depends on microtubules, proteins forming part of the cell’s cytoskeleton, which act as tracks for mitochondrial transport.

“Mitochondria need a road to move along, and that road is made up of microtubules,” Hill says. “It takes time for the microtubules to arrive and additional time for the mitochondria to get transported along them, which is why we see this delay.”

Implications for Future Research

Analysis of human microglia images showed similar mitochondrial patterns, affirming the mouse model’s relevance to human biology. “The mouse immune system models the human immune system very well, but it’s always good to confirm that what we’re seeing in the mouse is consistent in humans so that this can be translatable to developing therapeutics down the line,” Pietramale notes.

The Dartmouth study was published alongside a UCLA study in Nature Communications, which found that microglial mitochondria behave differently across brain regions and that mitochondrial genes influence microglial shape and function. “This was a great collaborative experience, and it shows how scientists can work together instead of competing,” Hill reflects.

With a clearer picture of microglial mitochondria in healthy cells, researchers are now investigating potential disruptions in disease and aging. “Our immediate next step is to examine this process in aging brains and brains with inflammation,” Pietramale says. “I’ve completed those experiments, and I’m excited to share those results in a future publication.”