Virginia Tech researchers have uncovered a crucial indicator in the brain that could enable earlier diagnosis of children affected by a rare genetic disorder. Their groundbreaking findings were recently published in EMBO Molecular Medicine.

Leigh syndrome, a severe neurological condition, targets the mitochondria—often referred to as the energy factories of the body. This disorder typically manifests in infancy, progressing rapidly and leaving limited treatment options, resulting in poor survival rates. Prenatal testing for mitochondrial disorders, including Leigh syndrome, is not commonly performed.

“If there’s not any real sign that you have something wrong with you at birth, they’re not going to recommend genetic testing or genetic counseling,” explained Alicia Pickrell, an associate professor in the School of Neuroscience at Virginia Tech. Without early screening, children with Leigh syndrome may appear to develop normally until they reach 9 or 10 months of age, at which point symptoms emerge and their condition deteriorates swiftly.

Unveiling Early Indicators

A clinical study from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has revealed that early signs of neurodevelopmental delay can often be detected before the disease begins to affect a patient’s motor and respiratory functions. This discovery prompted Pickrell and her team to explore new avenues for early intervention.

“The study is saying that these mutations don’t impact these patients out of the blue. These children were born with them,” Pickrell noted. She suggested that perhaps researchers have not been using the right tools or examining the correct brain areas, which could mean there is a potential to identify—and eventually treat—this disease sooner.

Research Collaboration and Findings

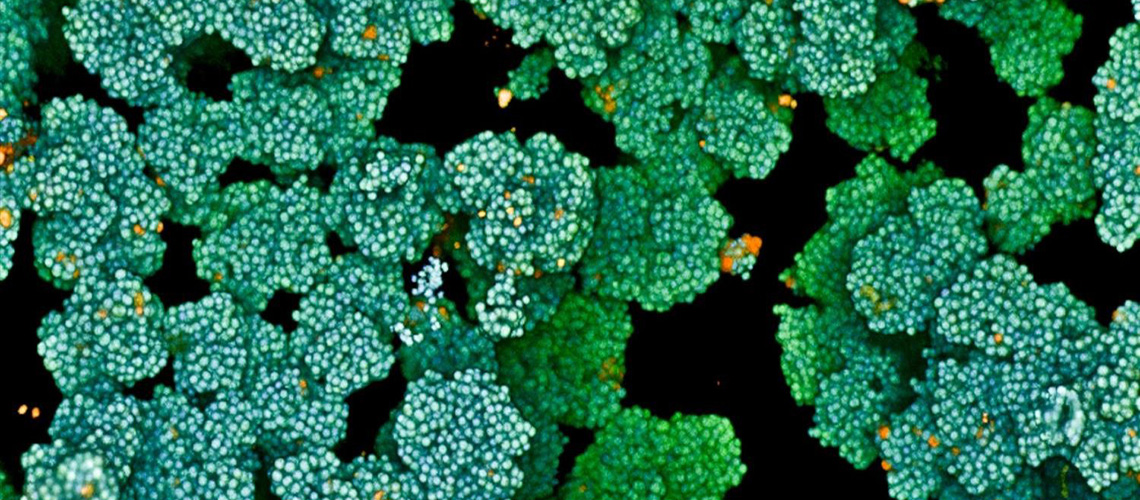

In collaboration with Paul Morton, assistant professor at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, and Sahitya Biswas, a student in the Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health Graduate Program, Pickrell evaluated Leigh syndrome symptoms using a mouse model. Their research revealed developmental defects and reduced activity within specialized neural stem cells shortly after birth.

The team identified a malformed region centered on the corpus callosum—a thick nerve tract that facilitates communication between the brain’s left and right hemispheres. Through microscopy, they observed a pattern of poor connections within this area.

“From the data we’ve been collecting, it looks like it’s just not developing the way it should,” Pickrell stated. “The neural stem cells aren’t generating the types of cells they are supposed to.”

Implications for Early Diagnosis and Treatment

With the newfound understanding of where to focus their efforts, researchers are optimistic about the potential to identify children with Leigh syndrome earlier, allowing them to participate in clinical trials sooner. This development represents a significant step forward in addressing the challenges associated with diagnosing and treating rare genetic disorders.

The announcement comes as scientists worldwide continue to seek innovative solutions to improve the prognosis for individuals with genetic diseases. As research progresses, the hope is that these findings will lead to more effective interventions and ultimately improve outcomes for those affected by Leigh syndrome and similar conditions.

Meanwhile, this study underscores the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in advancing medical research. By combining expertise from neuroscience, veterinary medicine, and translational biology, the Virginia Tech team has paved the way for future breakthroughs in the field.

As the scientific community builds on these findings, the potential for earlier diagnosis and intervention could transform the landscape of genetic disorder treatment, offering new hope to families affected by these challenging conditions.