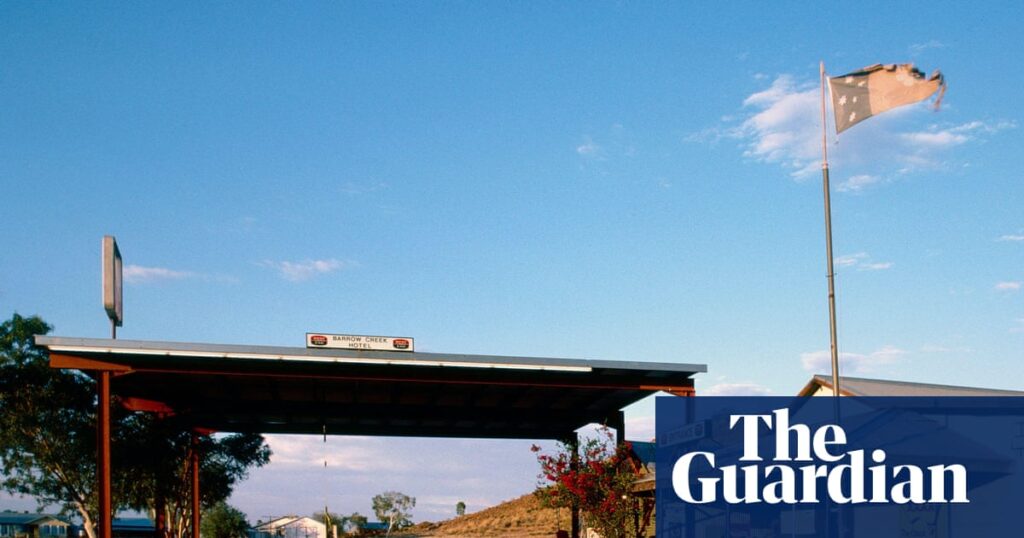

In a turn of events that echoes the lament of Australian country music legend Slim Dusty, the Barrow Creek Hotel, a historic outback pub located 283 kilometers up the Stuart Highway from Alice Springs, has been stripped of its liquor license as of January 1, 2026. This decision has left a 200-kilometer stretch of highway and several remote Aboriginal towns without a local watering hole, rendering the area, in Dusty’s words, “so lonesome, morbid or drear.”

The Barrow Creek Hotel, known not only for its rustic charm but also as the last place British backpacker Peter Falconio was seen alive before his tragic murder in 2001, now faces a new chapter in its storied history. The Northern Territory Liquor Commission’s decision to suspend the pub’s license was not due to violence but rather a series of complaints against its long-time publican, Les Pilton.

Complaints and Controversies

The liquor commission’s decision followed a hearing that considered ten grounds of complaints against Pilton, who has run the pub for 37 years. Among the issues were allegations of discriminatory practices, such as serving Indigenous customers through a hatchway while they stood outside, and using government-issued income management cards meant to prevent welfare spending on alcohol. Additionally, the pub was criticized for inadequate facilities, including broken windows in female toilets, exposed wiring, and a lack of meals and drinking water.

Despite these complaints, the commission acknowledged Pilton’s “close and apparently effective relationship with local drinkers,” which seemed to moderate excessive alcohol consumption. Local police also reported minimal alcohol-related issues in recent months, which counted in Pilton’s favor.

Assessing Fitness for License

The crux of the commission’s deliberations was whether Pilton was a “fit and proper person” to hold a liquor license at the heritage-listed pub. The commission accepted the testimony of liquor and licensing inspectors, who provided evidence supported by written records and audiovisual recordings. In contrast, Pilton’s evidence was described as “often evasive, inconsistent, argumentative or non-responsive.”

One contentious point was whether Pilton was aware that a man named Lachlan, lacking a responsible service of alcohol certificate, was serving alcohol. The commission found it “implausible” that Pilton was unaware of this, noting that Lachlan’s activities “beggar[ed] belief.”

Challenges and Responsibilities

Beyond his role as a publican, Pilton is also responsible for maintaining essential services in the remote location, such as power, water, and sewage disposal. The commission recognized Pilton’s long tenure and ability to keep the inn running in a challenging environment. Barrow Creek relies on non-potable bore water, and Pilton sources drinking water from Alice Springs, 283 kilometers away.

Commission chair Russell Goldflam noted that while Pilton’s old-school approach might not suit a modern metropolitan licensee, it does not necessarily disqualify him from running an outback pub. However, some of Pilton’s practices, such as serving Indigenous patrons through a hatchway, were less favorably viewed.

Path to Reinstatement

After upholding eight of the ten complaints, the commission suspended Pilton’s license until he meets specific requirements. These include expanding the licensed area, upgrading facilities, obtaining a food service certificate, and establishing reliable communication channels with liquor licensing authorities.

Pilton has expressed his intention to comply with these requirements, stating, “When that’s all completed, I’ll reopen.” The future of the Barrow Creek Hotel now hinges on Pilton’s ability to meet these conditions and restore the pub’s status as a community hub.

This development highlights the ongoing challenges faced by remote establishments in balancing tradition with modern regulatory expectations. As Pilton works towards reopening, the Barrow Creek Hotel remains a symbol of the unique and often complex character of the Australian outback.