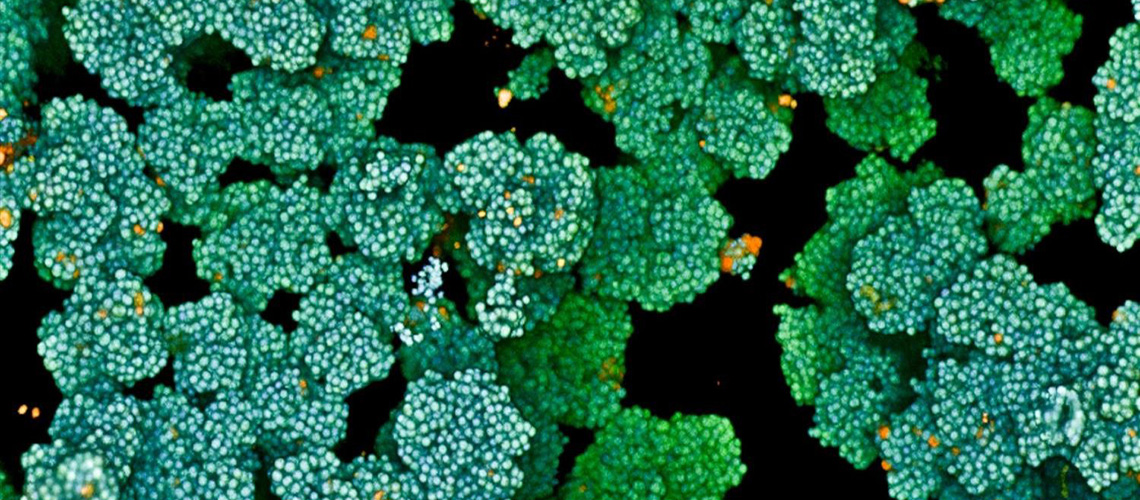

In a groundbreaking study, scientists have uncovered the distinct membrane binding properties of non-visual arrestins, shedding light on their critical role in cellular signaling. This discovery, published in the latest issue of Nature Communications, provides new insights into the complex mechanisms of G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, a fundamental process in cell communication.

The research, led by a team from Vanderbilt University, delves into how non-visual arrestins interact with cell membranes, a topic that has long intrigued scientists due to its implications for drug development and disease treatment. Arrestins, known for their role in turning off GPCR signals, are now shown to have unique binding properties that differentiate them from their visual counterparts.

Understanding GPCR Signaling

GPCRs are a large family of cell surface receptors that respond to various external signals, playing a pivotal role in numerous physiological processes. The regulation of these receptors is crucial, as it ensures that signals are appropriately modulated and terminated. Arrestins, particularly non-visual arrestins, are key players in this regulatory mechanism.

According to Dr. Vsevolod Gurevich, a leading researcher in the study, “Non-visual arrestins have evolved to perform specialized functions in different tissues, and their ability to bind to membranes in unique ways is essential for their role in signaling.” This finding highlights the complexity and specificity of cellular signaling pathways.

Historical Context and Previous Research

The study of arrestins has a rich history, with initial discoveries focusing on visual arrestins involved in the desensitization of rhodopsin, a light-sensitive receptor in the eye. Over the years, research expanded to non-visual arrestins, revealing their involvement in broader physiological processes.

Previous studies, such as those by Lefkowitz and Luttrell, have established the foundational understanding of arrestin-mediated GPCR regulation. These works have paved the way for current research, which now explores the nuanced roles of arrestins in non-visual contexts.

Key Findings and Methodology

The recent study employed advanced techniques, including genetically encoded crosslinkers and (19)F-NMR spectroscopy, to investigate the structural dynamics of non-visual arrestins. These methods allowed researchers to observe how arrestins interact with different membrane environments, providing a detailed view of their binding mechanisms.

The team discovered that non-visual arrestins exhibit a preference for specific phosphoinositides, a class of lipids found in cell membranes. This preference influences how arrestins regulate GPCR signaling, affecting processes such as receptor desensitization and endocytosis.

“Our findings reveal that the membrane binding of non-visual arrestins is not merely a passive interaction but a highly selective and dynamic process,” said Dr. Gurevich.

Implications for Drug Development

The implications of these findings are significant for drug development, particularly in the design of therapies targeting GPCRs. Understanding the distinct binding properties of non-visual arrestins can lead to more precise modulation of GPCR activity, potentially improving the efficacy and specificity of drugs.

Experts suggest that these insights could aid in the development of treatments for diseases such as heart failure, where GPCR signaling plays a critical role. By targeting the unique interactions of non-visual arrestins, new therapeutic strategies could emerge.

Future Directions and Challenges

While the study provides valuable insights, it also raises new questions about the broader roles of arrestins in cellular signaling. Future research will likely explore how these findings can be translated into clinical applications and whether similar mechanisms exist in other signaling pathways.

Dr. Gurevich and his team plan to continue their investigations, focusing on the potential for arrestins to serve as therapeutic targets. “Our work is just the beginning,” he noted. “There is much more to learn about the intricate dance between arrestins and cell membranes.”

As the scientific community continues to unravel the complexities of cellular signaling, the distinct membrane binding properties of non-visual arrestins stand out as a promising area for further exploration and innovation.