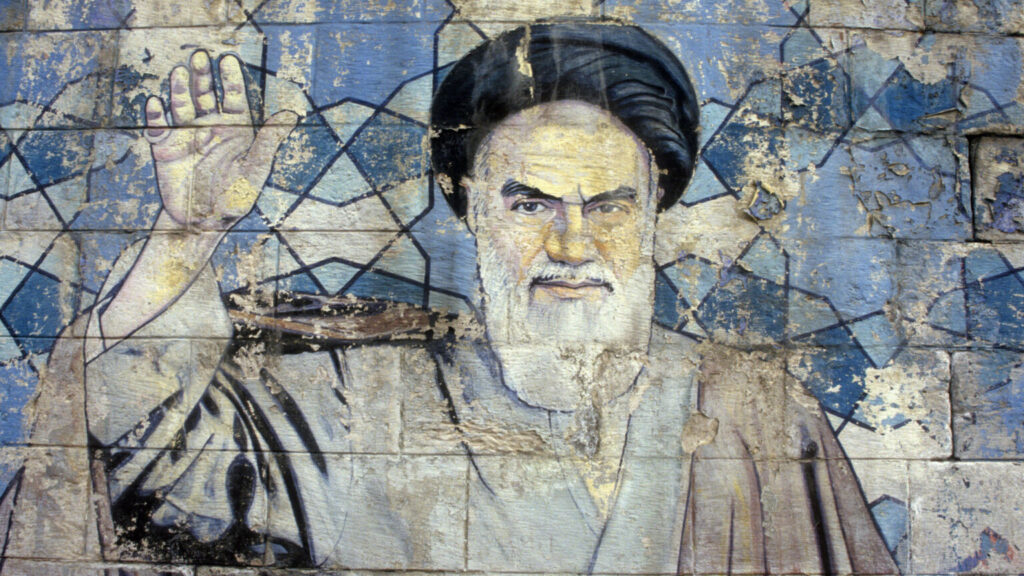

A collection of art work in the form of murals, billboards, banners and posters intended for propaganda purposes. Photographed on the streets of Tehran in the years since the Islamic Revolution. c1985 (Photo by Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images)

In the autumn of 1978, Iran’s political landscape was on the brink of a seismic shift. The deeply unpopular monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah, faced mounting pressure not just from the religious right, but significantly from the Iranian left. This pressure emanated from Tehran’s burgeoning student population, the Stalinist Tudeh Party, and a restive, unionized working class. The catalyst for this unrest was a widespread oil-workers’ strike, particularly in Khuzestan in September 1978, which brought the nation’s tensions to a head.

The shah’s attempts to quell the strikes and protests culminated in the infamous Black Friday massacre, where security forces killed between 60 and 100 demonstrators in Tehran’s Jaleh Square. This brutal crackdown only intensified the rebellion, leading to a general strike that nearly paralyzed the country. By early 1979, the shah realized his reign was untenable, and in January, he fled Iran, taking with him a small box of Iranian soil. Just two weeks later, Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile, and by February 11, 1979, the Iranian monarchy was officially dissolved.

The Rise of the Islamic Republic

In the aftermath of the shah’s departure, the Iranian left, including parties like the Tudeh and the People’s Mojahedin Organisation, supported Khomeini’s proposal for a referendum to establish an Islamic Republic. The referendum passed with overwhelming support, marking the beginning of a new era. However, this transition was fraught with irony and tragedy for the leftists who had played a crucial role in the revolution.

The Iranian Revolution, fueled by the courage and agitation of workers and dominated by left-wing forces, paradoxically led to the establishment of an ultra-reactionary Islamist regime. The leftists, who had allied with Islamists to overthrow the shah, soon found themselves repressed by the very regime they helped bring to power.

The Unfortunate Alliance

The alliance between the Iranian left and the Islamists was an unmitigated disaster for the former. In retrospect, the reasons for this alliance and its rapid dissolution are complex. Many leftist parties were weak and opportunistic, with their leading figures imprisoned by the shah. Moreover, their ideological disorganization was no match for the lethal clarity and leadership of Khomeini, who commanded the loyalty of the mullahs, clerics, and worshippers.

According to experts, the key issue was the Iranian left’s fixation on anti-imperialism. They viewed Khomeini and his Islamist supporters as allies against the shah, who was seen as a tool of Western powers. This perspective was shaped by the 1953 coup, which saw a democratically elected prime minister overthrown with the aid of the CIA and MI6 to protect British oil interests.

“The Iranian Revolution was framed as a cultural battle, rather than a political, economic, or class-based struggle,” noted historian Ali Ansari. “It was a movement against Gharbzadegi, or ‘Westoxification,’ a term popularized by Jalal Al-e-Ahmad.”

A Cultural Revolution

The revolution was not just a political upheaval; it was a cultural one. It aimed to rid Iran of Western influence, as articulated by leftist thinkers like Sorbonne-educated sociologist Ali Shariati. He and others envisioned a revolution that would free Iran’s essence, reimagined as religious and socialist, from Western dominance.

Despite their ideological differences, leftists and Islamists shared a disdain for Western modernity and its monarchical representative in Iran. This common ground allowed them to collaborate against the shah, but their unity was short-lived. After the shah’s fall, the leftists found themselves sidelined as Khomeini consolidated power.

The Aftermath and Lessons Learned

Following the establishment of the Islamic Republic, Khomeini swiftly moved to solidify his control. He became Iran’s lifelong Supreme Leader, subordinated parliament to an assembly of clerics, and established a shadow government. This new regime targeted the remnants of the Iranian left, suppressing trade unions and silencing the working class. Thousands of political opponents faced trials in revolutionary courts, often leading to executions.

“Blinded by anti-Westernism, leftists couldn’t see the Islamist menace right in front of their eyes,” observed political analyst Hamid Dabashi. “When they finally did, it was already far too late.”

The Iranian Revolution serves as a cautionary tale for the left. It highlights the dangers of alliances formed on narrow ideological grounds without a clear understanding of potential consequences. As Iran’s experience shows, such alliances can lead to unintended and tragic outcomes.

Today, as the world grapples with complex political landscapes, the lessons from Iran’s 1979 Revolution remain relevant. They underscore the importance of critical evaluation and strategic foresight in political movements, reminding us that the pursuit of change must be guided by a comprehensive vision for the future.