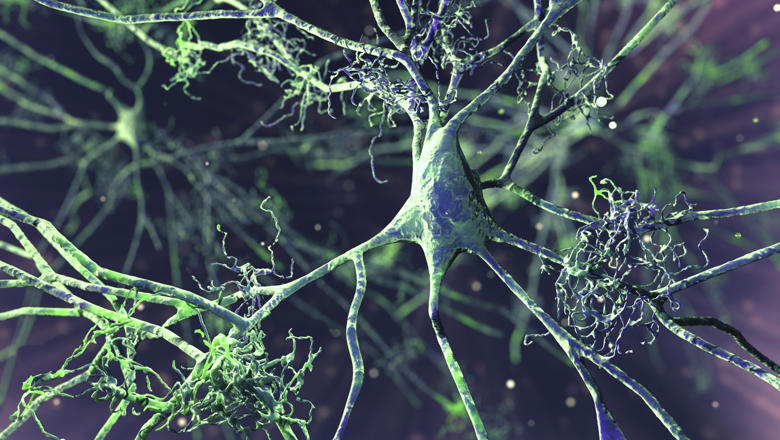

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) models have profoundly transformed digital content creation, making it increasingly difficult to remember a time before their existence. These AI tools are often employed for creative digital projects like videos and photos, yet their influence has not fully extended into the physical realm. The question arises: why haven’t we seen generative AI-enabled personalized objects, such as phone cases and pots, become commonplace in homes, offices, and stores?

According to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), the primary challenge lies in the mechanical integrity of 3D models. While AI can generate personalized 3D models ready for fabrication, these systems often overlook the physical properties necessary for real-world application. MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) PhD student and CSAIL engineer Faraz Faruqi has been exploring this balance, developing AI-based systems that can aesthetically modify designs while preserving their functionality, and another that adjusts structures to achieve desired tactile properties.

From Concept to Reality

In collaboration with researchers from Google, Stability AI, and Northeastern University, Faruqi has developed a method to create real-world objects with AI, producing items that are both durable and visually appealing. The AI-powered “MechStyle” system allows users to upload a 3D model or choose from preset assets like vases and hooks, prompting the tool with images or text to craft a personalized version. A generative AI model then alters the 3D geometry, while MechStyle simulates the impact of these changes on specific parts, ensuring that vulnerable areas remain structurally sound. Once the AI-enhanced blueprint is satisfactory, it can be 3D printed and used in the real world.

For instance, users can select a model of a wall hook and the material for printing, such as polylactic acid plastic. They can then instruct the system to create a personalized version, with prompts like “generate a cactus-like hook.” The AI model collaborates with the simulation module to produce a 3D model resembling a cactus that retains the structural properties of a hook. This green, ridged accessory can be used to hang mugs, coats, and backpacks. Such creations are made possible by a stylization process where the system modifies a model’s geometry based on its understanding of the text prompt, working with feedback from the simulation module.

Ensuring Structural Viability

CSAIL researchers highlight that 3D stylization previously led to unintended consequences. Their initial study found that only about 26 percent of 3D models remained structurally viable after modification, indicating that the AI system did not fully comprehend the physics of the models it was altering.

“We want to use AI to create models that you can actually fabricate and use in the real world,” says Faruqi, a lead author on a paper presenting the project. “So MechStyle actually simulates how GenAI-based changes will impact a structure. Our system allows you to personalize the tactile experience for your item, incorporating your personal style into it while ensuring the object can sustain everyday use.”

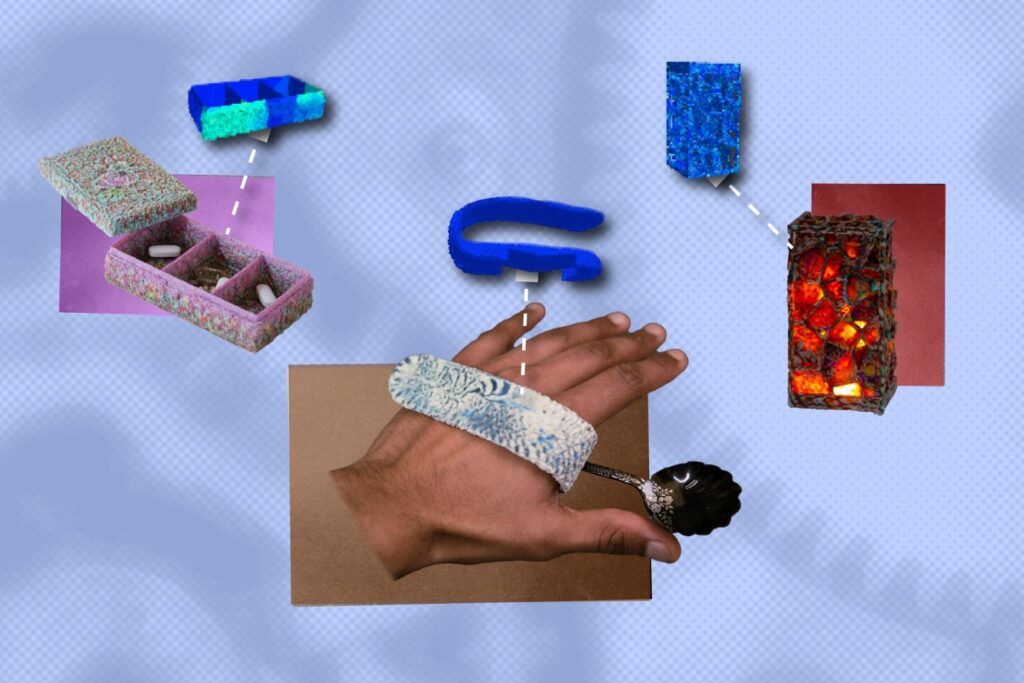

This computational thoroughness could eventually enable users to personalize their belongings, creating unique items such as eyeglasses with speckled blue and beige dots resembling fish scales, or a pillbox with a rocky texture checkered with pink and aqua spots. The system’s potential extends to crafting unique home and office decor, like a lampshade resembling red magma, and designing assistive technology tailored to users’ specifications, such as finger splints for dexterous injuries and utensil grips for motor impairments.

Future Applications and Expert Insights

In the future, MechStyle could be instrumental in creating prototypes for accessories and other handheld products for sale in toy shops, hardware stores, or craft boutiques. The goal, according to CSAIL researchers, is for both expert and novice designers to focus more on brainstorming and testing different 3D designs, rather than assembling and customizing items by hand.

To ensure MechStyle’s creations withstand daily use, the researchers integrated their generative AI technology with a type of physics simulation known as finite element analysis (FEA). This process visualizes a 3D model, such as a pair of glasses, with a heat map indicating which regions are structurally viable under realistic weight and which are not. As AI refines the model, the physics simulations highlight weakening parts, preventing further changes.

Faruqi notes that running these simulations each time a change is made significantly slows the AI process. Therefore, MechStyle is designed to know when and where to conduct additional structural analyses. “MechStyle’s adaptive scheduling strategy keeps track of what changes are happening in specific points in the model. When the genAI system makes tweaks that endanger certain regions of the model, our approach simulates the physics of the design again. MechStyle will make subsequent modifications to make sure the model doesn’t break after fabrication.”

Combining the FEA process with adaptive scheduling enabled MechStyle to generate objects that were up to 100 percent structurally viable. Testing 30 different 3D models with styles resembling bricks, stones, and cacti, the team discovered that the most efficient way to create structurally viable objects was to dynamically identify weak regions and adjust the generative AI process to mitigate its effects. In these scenarios, researchers found they could either halt stylization completely when a stress threshold was reached or gradually make smaller refinements to prevent at-risk areas from reaching that point.

The system also offers two modes: a freestyle feature that allows AI to quickly visualize different styles on a 3D model, and a MechStyle mode that carefully analyzes the structural impacts of tweaks. Users can explore different ideas, then try the MechStyle mode to see how artistic flourishes affect the durability of specific model regions.

CSAIL researchers add that while their model ensures structural soundness before 3D printing, it cannot yet improve 3D models that were non-viable from the start. If such a file is uploaded to MechStyle, an error message will appear. However, Faruqi and his colleagues aim to enhance the durability of these faulty models in the future.

Moreover, the team hopes to use generative AI to create 3D models for users, rather than merely stylizing presets and user-uploaded designs. This would make the system even more user-friendly, allowing those less familiar with 3D models or unable to find their design online to generate it from scratch. For example, if someone wanted to fabricate a unique type of bowl unavailable in a repository, AI could create it instead.

“While style-transfer for 2D images works incredibly well, not many works have explored how this transfer to 3D,” says Google Research Scientist Fabian Manhardt, who wasn’t involved in the paper. “Essentially, 3D is a much more difficult task, as training data is scarce and changing the object’s geometry can harm its structure, rendering it unusable in the real world. MechStyle helps solve this problem, allowing for 3D stylization without breaking the object’s structural integrity via simulation. This gives people the power to be creative and better express themselves through products that are tailored towards them.”

Faruqi authored the paper with senior author Stefanie Mueller, an MIT associate professor and CSAIL principal investigator, and two other CSAIL colleagues: researcher Leandra Tejedor SM ’24, and postdoc Jiaji Li. Their co-authors include Amira Abdel-Rahman PhD ’25, now an assistant professor at Cornell University, Martin Nisser SM ’19, PhD ’24, Google researcher Vrushank Phadnis, Stability AI Vice President of Research Varun Jampani, MIT Professor and Center for Bits and Atoms Director Neil Gershenfeld, and Northeastern University Assistant Professor Megan Hofmann.

Their work was supported by the MIT-Google Program for Computing Innovation and was presented at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Symposium on Computational Fabrication in November.