The mucosal surfaces lining the human body are fortified with defensive molecules that prevent microbes from causing inflammation and infections. Among these molecules are lectins—proteins that recognize microbes and other cells by binding to sugars on cell surfaces. In a groundbreaking study, MIT researchers have identified a lectin named intelectin-2 with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

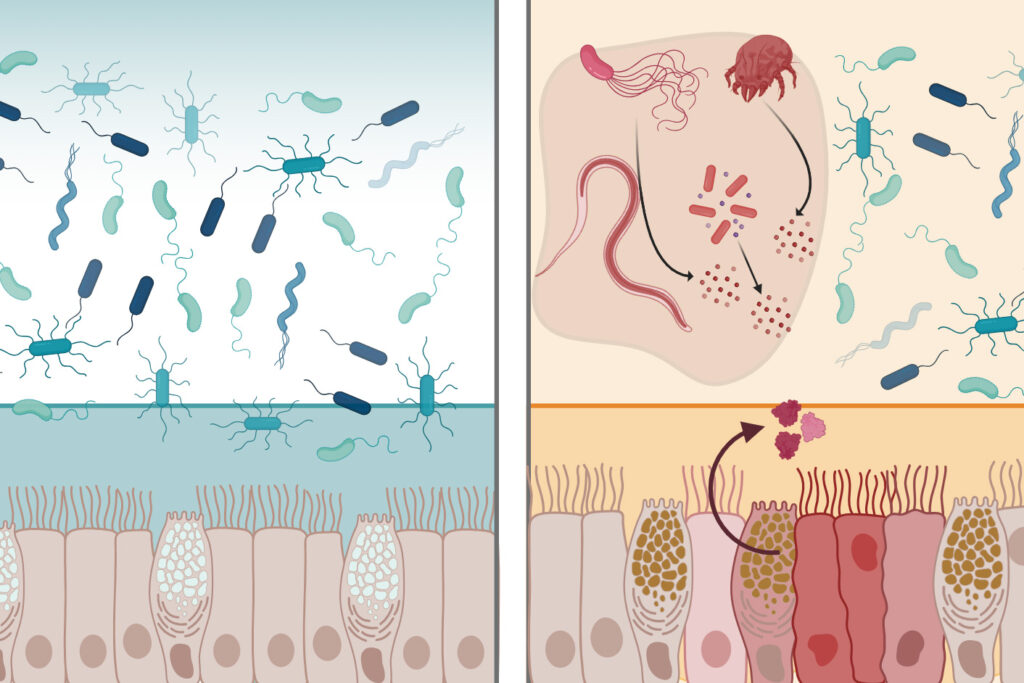

Intelectin-2 binds to sugar molecules on bacterial membranes, trapping the bacteria and hindering their growth. Additionally, it can crosslink molecules that make up mucus, bolstering the mucus barrier. “What’s remarkable is that intelectin-2 operates in two complementary ways. It helps stabilize the mucus layer, and if that barrier is compromised, it can directly neutralize or restrain bacteria that begin to escape,” says Laura Kiessling, the Novartis Professor of Chemistry at MIT and the senior author of the study.

Unveiling the Multifunctional Protein

This discovery could make intelectin-2 a promising candidate for therapeutic applications, particularly in strengthening the mucus barrier in patients with disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease. Amanda Dugan, a former MIT research scientist, and Deepsing Syangtan PhD ’24 are the lead authors of the paper, which appears in Nature Communications.

The human genome encodes more than 200 lectins, which are carbohydrate-binding proteins playing various roles in the immune system and cellular communication. Kiessling’s lab has been delving into lectin-carbohydrate interactions, focusing on a family of lectins called intelectins. In humans, this family includes two lectins: intelectin-1 and intelectin-2.

While both proteins have similar structures, intelectin-1 is unique in its ability to bind carbohydrates found in bacteria and other microbes. About a decade ago, Kiessling and her team discovered intelectin-1’s structure, but its functions remain partially understood. At the time, scientists speculated that intelectin-2 might play a role in immune defense, but evidence was scarce.

The Role of Intelectin-2 in Immune Defense

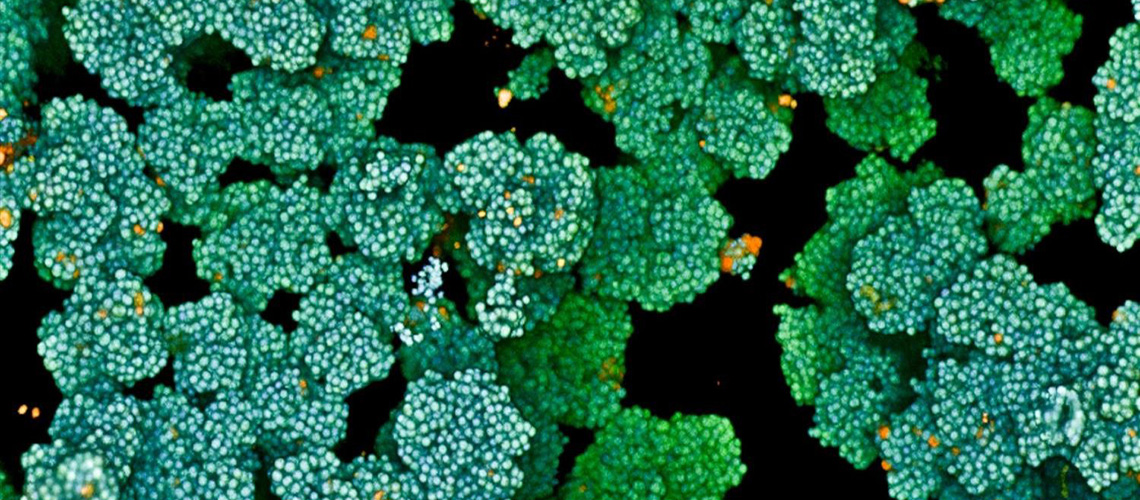

In humans, intelectin-2 is consistently produced by Paneth cells in the small intestine. In mice, its expression from mucus-producing Goblet cells is triggered by inflammation and certain parasitic infections. The new study reveals that both human and mouse intelectin-2 bind to a sugar molecule called galactose, commonly found in mucins that constitute mucus.

When intelectin-2 binds to these mucins, it fortifies the mucus barrier. Galactose is also present in carbohydrates on some bacterial cells’ surfaces. The researchers demonstrated that intelectin-2 can bind to microbes displaying these sugars, including many pathogens causing GI infections.

“Intelectin-2 first reinforces the mucus barrier itself, and then if that barrier is breached, it can control the bacteria and restrict their growth,” Kiessling says.

Implications for Treating Infections

Over time, the trapped microbes disintegrate, suggesting that intelectin-2 can kill them by disrupting their cell membranes. This antimicrobial activity affects a wide range of bacteria, including some resistant to traditional antibiotics. These dual functions protect the GI tract lining from infection.

In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, intelectin-2 levels can become abnormally high or low. Low levels could lead to mucus barrier degradation, while high levels might eliminate too many beneficial gut bacteria. Restoring the correct levels of intelectin-2 could benefit these patients.

Kiessling notes, “Our findings show just how critical it is to stabilize the mucus barrier. Looking ahead, we can imagine exploiting lectin properties to design proteins that actively reinforce that protective layer.”

Future Directions and Potential Applications

Intelectin-2’s ability to neutralize pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae, often difficult to treat with antibiotics, suggests its potential as an antimicrobial agent. “Harnessing human lectins as tools to combat antimicrobial resistance opens up a fundamentally new strategy that draws on our own innate immune defenses,” Kiessling says. “Taking advantage of proteins that the body already uses to protect itself against pathogens is compelling and a direction that we are pursuing.”

The research received funding from the National Institutes of Health Glycoscience Common Fund, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Science Foundation. Other contributors include Charles Bevins, a professor of medical microbiology and immunology at the University of California at Davis School of Medicine; Ramnik Xavier, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; and Katharina Ribbeck, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor of Biological Engineering at MIT.

This development marks a significant step forward in understanding the body’s natural defenses and offers promising avenues for future research and therapeutic strategies.