In a groundbreaking study, researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) are exploring why certain wild species adapt better to environmental changes than others. This research, led by statistician Kenneth Aase, employs a novel mathematical approach that could significantly advance our understanding of biodiversity loss. Aase, a PhD research fellow at NTNU’s Department of Mathematical Sciences, is part of the GPWILD project, funded by a European Research Council Consolidator Grant. The project uses a combination of biology and mathematics to study the adaptive evolutionary potential of species, relying heavily on genetic and body data from tens of thousands of house sparrows in Norway’s Helgeland district.

The research focuses on house sparrows because these birds are ideally suited for such studies. “Because our island populations are small and delimited, they are exceptionally well suited for research. Biologists can record and follow almost all individual sparrows from birth until they die,” Aase explained. NTNU researchers have been studying these sparrows for over 30 years, creating an invaluable long-term dataset that provides insights into survival, reproduction, and the consequences of environmental changes.

Genomic Prediction: A Tool for Conservation

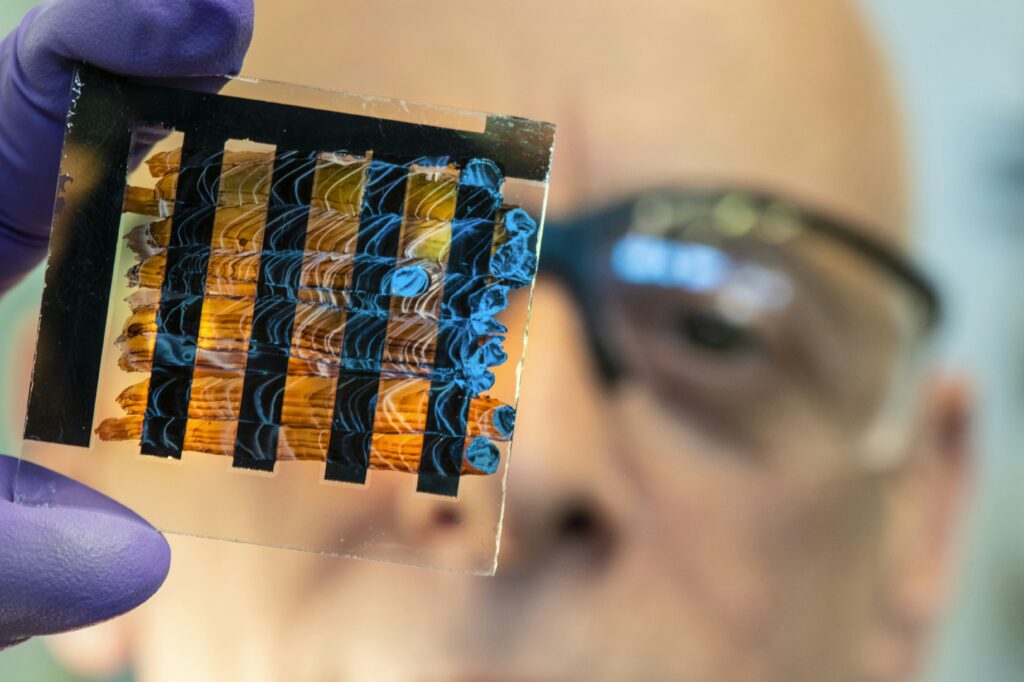

Aase’s work centers on genomic prediction (GP), a statistical method that determines how an individual’s genes influence traits. This technique, widely used in plant and animal breeding, has not been extensively applied to wild populations until now. “The method can also tell us whether the genes of a given house sparrow will give it a higher or lower body weight. This is important for the sparrow’s ability to survive,” Aase noted. As access to genetic material from wild populations increases, Aase and his team, led by Professor Stefanie Muff, are investigating GP’s potential in ecology, evolution, and conservation biology.

The researchers use genetic markers from a “training group” to predict traits in individuals, even if those traits haven’t been directly measured. “As long as we have information from the same genetic markers in both the training group and the individual, we can calculate how the genes affect the trait,” Aase said. However, they found that predictions are more accurate within the same population than across different populations, a finding consistent with previous studies in breeding and medical research.

Challenges and Opportunities in Wild Populations

Applying GP to wild populations presents unique challenges. “For us statisticians, perhaps the biggest challenge is that field datasets are often incomplete. We do not always get genetic data or measurements of all individuals,” Aase explained. Despite these challenges, the comprehensive house sparrow dataset from Helgeland offers a rare opportunity for thorough and long-term study.

“As a statistician, I am fortunate to have the data served on a silver platter by the biologists I collaborate with at the Gjærevoll Centre and the Department of Biology at NTNU,” Aase said. This collaboration allows him to conduct advanced statistical analyses, often using NTNU’s supercomputer IDUN for the most complex computations.

Implications for Biodiversity and Conservation

The world is facing what many scientists call the “sixth mass extinction,” driven by human activity and environmental changes. Understanding how species adapt to these changes is crucial for conservation efforts. “Climate change and increased land use mean that many populations of wild animals and plants are exposed to increased external pressure and faster environmental changes,” Aase said. GP can provide insights into how viable individuals are under specific environmental conditions, aiding in the reintroduction or strengthening of populations.

“Studies of house sparrows in populations along the Norwegian coast can help us preserve populations of other species that are threatened with extinction due to the changes we humans make in nature,” Aase emphasized. This research not only enhances our understanding of natural processes but also informs targeted conservation measures.

Future Directions: Expanding the Research

As Aase continues his PhD research, he plans to expand the use of genomic prediction to other species, including Svalbard reindeer, Scottish deer, arctic foxes, and various bird species. “In GPWILD, we’re going to put these questions into a broader framework,” he said. However, his work with house sparrows is far from over. “Currently, I am working on an applied study where GP is used to investigate how certain genetic processes affect the fitness of the house sparrow,” Aase added.

The insights gained from this research are expected to play a vital role in addressing the biodiversity crisis. “If we want to stop this development through targeted measures, we need both good analytical tools and basic knowledge about how evolution in nature works,” Aase concluded.

Reference: Kenneth Aase, Hamish A Burnett, Henrik Jensen, Stefanie Muff, “How accurate is genomic prediction across wild populations?”, Evolution, Volume 79, Issue 12, December 2025, Pages 2612–2628, https://doi.org/10.1093/evolut/qpaf202