The Simpsons is getting experimental in its old age. With 36 seasons complete and a renewal through a 40th secured, the show has entered territory previously occupied mostly by non-prime-time stalwarts like Saturday Night Live and Meet the Press—television institutions that run for much longer than the typical sitcom or drama. Perhaps conscious that the animated comedy has now lasted five to ten times longer than a normal sitcom, the 36th season has repeatedly toyed with the idea of what a series finale might look like, even though no such thing is anywhere in sight.

For the season’s premiere back in the fall, it created a fake series finale, hosted by Conan O’Brien, that featured forever-10-year-old Bart turning 11 and reacting badly to a number of finale-style abrupt changes to the status quo. In the last episode of season 36, “Estranger Things,” the show flashed forward to a future where family matriarch Marge has passed away and a gradual estrangement has developed between now-adult Bart and Lisa. Homer remains alive, with the show repeatedly underlining how unlikely it seems that he would outlive his patient, cautious, and seemingly healthy spouse.

Is Marge Really Gone?

As fans caught up with the season on streaming, the finale has created a mild headline-generating controversy over whether Marge is “really” dead, most likely among less consistent viewers who might dip back in occasionally or get their news about the show from the internet rather than watching it. Of course, she’s not; “Estranger Things” is one of many flash-forward episodes the show has done over the years, generally understood to be alternate versions of the future, not pieces of a vast and interconnected timeline. The show’s flashbacks are similarly intentionally contradictory; early on, Marge and Homer were young parents in the 1980s; as the show got older and they stayed the same age, subsequent flashbacks were brought further and further into the timeline.

But one reason “Marge is dead” has seemingly caught fire as an internet curiosity may have to do with the unexpectedly mortality creeping in around the edge of the show. Anyone who has watched The Simpsons in recent years, especially if they’ve seen a new episode juxtaposed with an older one, would have to take note of how different the characters sound. Animation may be able to preserve a character’s basic look and inure them from ageing, but it cannot defeat what the show once called the ravages of time.

The Changing Voices of Springfield

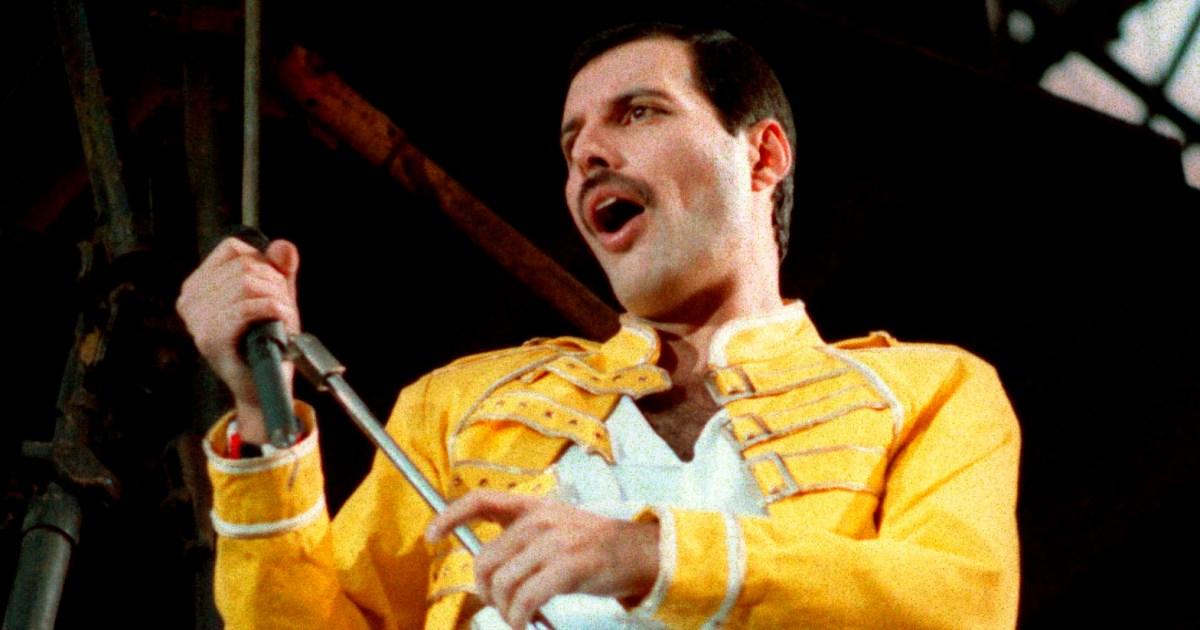

The Simpsons has employed a core of voice actors for nearly four decades, and who among us sound precisely the same as we did 40 years ago, if we’re so lucky to have that comparison point? Marge is the character where this is most noticeable—more so than characters whose voices have been replaced by new actors for reasons of racial sensitivity. Julie Kavner, the distinctive actor who has given one of the great long-term voiceover performances of TV history, turns 75 this year, while Marge is forever on the cusp of 40. Certain line readings will sound very close to the “original” Marge voice. More often, though, we’re getting a raspier, scratchier version that sounds more like Marge’s occasionally seen mother, also voiced by Kavner in a more whispery register.

Harry Shearer, who voices more than a dozen major supporting characters including Mr. Burns, Principal Skinner, and Ned Flanders, also sounds deeper and older in recent years. This evolution in voice quality adds a layer of authenticity to the characters, reflecting the passage of time that the animation itself cannot capture.

Creative Evolution and Future Prospects

That’s all on top of the show’s creative changes—some of which have been quite good. Under showrunner Matt Selman, the show has upped its game in recent years, actively pursuing more ambitious, format-challenging, and emotionally resonant stories. Not all of them are golden-years-level funny, but the creators feel engaged with their institution, and sometimes they’ve even taken advantage of the modified vocals; in one recent holiday episode, Ned Flanders sounded genuinely grief-stricken in part due to Shearer’s inability to hit the higher range of his usual tone.

Even when the actors’ changes do sound jarring, obviously it’s not anyone’s fault. People age—and intellectual property, at least lately, seems to insist on defying that process, creating a difficult-to-resolve conflict. The show obviously isn’t ever going to permanently kill off any of the family members, but at some point, they may be in the position of hiring someone new to voice Marge, or augmenting the performance with AI. The finale already introduced a new voice for Bart’s best friend Milhouse, following the retirement of longtime voice artist Pamela Hayden.

The Emotional Core of “Estranger Things”

Maybe that’s why the most poignant element of “Estranger Things” isn’t the death of Marge, which is handled lightly, avoiding the immediate devastation of grief with just a brief cursory shot of her funeral, and ending the episode with a short scene of her happily looking down upon her family from heaven. Rather, the emotional core of the episode is the sequence in which Bart and Lisa abruptly grow out of their beloved Itchy and Scratchy cartoons after realizing the show is now also marketed toward babies, with cutesy versions of the characters adorning little sister Maggie’s pyjamas.

Despite the show’s jokes, the idea of the Bart/Lisa bond breaking over Itchy and Scratchy, and Marge’s distress over it, is a potent one, maybe because it’s precisely the kind of uncharacteristic change alluded to in the season premiere. The Simpsons has been lampshading its ability to reset its characters for decades at this point; that’s the connective tissue between its heritage as a sitcom from another age and as a cartoon across the ages. In “Estranger Things,” it’s depicting a natural process less seismic but no less constant than death: letting go of once-beloved media and the real-world habits that accompany it.

Plenty of fans will have the opportunity to let go of The Simpsons, whether by chance or by choice. The show itself, good as it sometimes is, can only play at that farewell process, experimenting with what-ifs typically subsumed into the status quo. The real question isn’t whether Marge Simpson will live on, but how long the show will keep contemplating endings it can’t have.