image description

From morning glories spiraling up fence posts to grape vines corkscrewing through arbors, twisted growth is a common phenomenon in the plant kingdom. This unique adaptation allows plants to navigate obstacles, with roots often “doing the twist” to avoid rocks and other debris. While scientists have long understood that mutations in certain genes affecting microtubules can cause plants to grow in a twisting manner, the evolutionary prevalence of this trait has remained a mystery—until now.

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis, led by Ram Dixit, the George and Charmaine Mallinckrodt Professor of Biology, have discovered a potential explanation for this widespread adaptation. Their findings, recently published in Nature Communications, reveal that a full null mutation is not necessary for twisted growth. Instead, a change in gene expression in the plant epidermis is sufficient.

The Role of Gene Expression in Plant Epidermis

“That might explain why this is so widespread: you don’t need null mutations for this growth habit, you just need ways to tweak certain genes in the epidermis alone,” said Dixit, who also chairs the biology department in Arts & Sciences. This discovery emerged from the collaborative efforts of the National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center for Engineering Mechanobiology (CEMB), a consortium that unites biologists, engineers, and physicists to explore how physical forces shape living systems.

Guy Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering and co-director of CEMB, emphasized the significance of this interdisciplinary approach. “By combining biological experiments with mechanical modeling, we uncovered a fundamental principle: the outermost layer of the root dominates its twisting behavior through the same torsion physics that explains why hollow tubes can be almost as strong as solid rods. Geometry matters enormously.”

Feeding a Changing World

Understanding how roots navigate soil is becoming increasingly urgent as climate change intensifies droughts and forces agriculture onto marginal lands with rocky, compacted soils. Crops with root systems that can thrive in challenging conditions are essential for future food security.

“Roots are the hidden half of agriculture,” remarked Charles Anderson, a professor of biology and CEMB leader at Pennsylvania State University. “A plant’s ability to find water and nutrients depends entirely on how its roots explore the soil. If we can understand how roots twist and turn past obstacles, we could help crops survive in places they currently cannot.”

Twisted growth also plays a role in how vines climb, how stems resist wind, and how plants anchor themselves against erosion—factors critical for both food security and ecosystem resilience.

Solving the Mystery of Twisted Growth

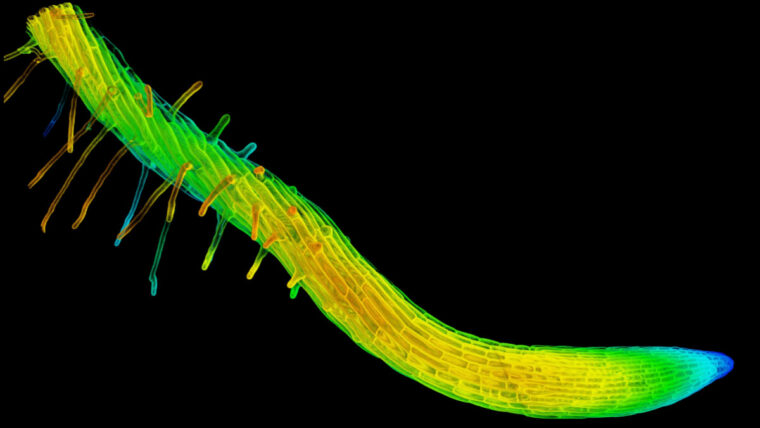

Using a model plant system where roots can skew right or left, Natasha Nolan, a former PhD student, investigated which plant cell layers regulate twisting behavior. The research team hypothesized that the twists emerge from the inner cortical layer, where mutations cause cells to be short and wide instead of long and skinny. The epidermal layer must “lean over” to maintain its structural integrity and reach its squat cortical-layer neighbors.

Nolan’s experiments revealed a striking finding: expressing the wild-type gene in any of the inner cell layers resulted in plants that still resembled the null twisty mutant. However, when the wild-type gene was expressed only in the epidermis, the roots straightened. “The dominating cell layer, that’s really dictating this behavior, is the epidermis,” Dixit explained.

“Somehow the epidermal cell layer is able to entrain inner cell layers,” Dixit said. “The epidermis is not a passive skin, but instead a mechanical coordinator of the growth of the entire organ.”

Implications for Agricultural Science

Now that scientists understand how plants “do the twist,” they can apply these findings to address agricultural challenges. “Imagine being able to design plants that dial up or dial down a root’s tendency to twist,” Anderson suggested. “In rocky, inhospitable conditions, you might want roots that corkscrew past obstacles. This research gives us a target and a mechanical framework for thinking about root architecture as an engineering problem.”

Genin highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in achieving these insights. “A biologist alone might have found that the epidermis matters, but wouldn’t have had the tools to explain why. An engineer alone couldn’t have done the genetics and phenotyping,” he said. “Together, as a center, we got the full picture.”

This groundbreaking research, supported by the Center for Engineering Mechanobiology and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, paves the way for future innovations in plant science and agriculture. As climate change continues to reshape our world, understanding and harnessing the power of twisted growth could prove vital in ensuring food security and ecosystem resilience.

Nolan, N., Jaafar, L., Fan, Y. et al. The epidermis coordinates multi-scale symmetry breaking in chiral root growth. Nat Commun 16, 11022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66029-8