Europe is currently navigating a complex geopolitical landscape, grappling with a resurgent Russia, trade tensions with the United States, and internal challenges related to migration. Amidst these pressing issues, a new economic challenge has emerged: the so-called Second China Shock. This phenomenon refers to the influx of high-tech exports from China, a development that threatens to reshape Europe’s economic landscape.

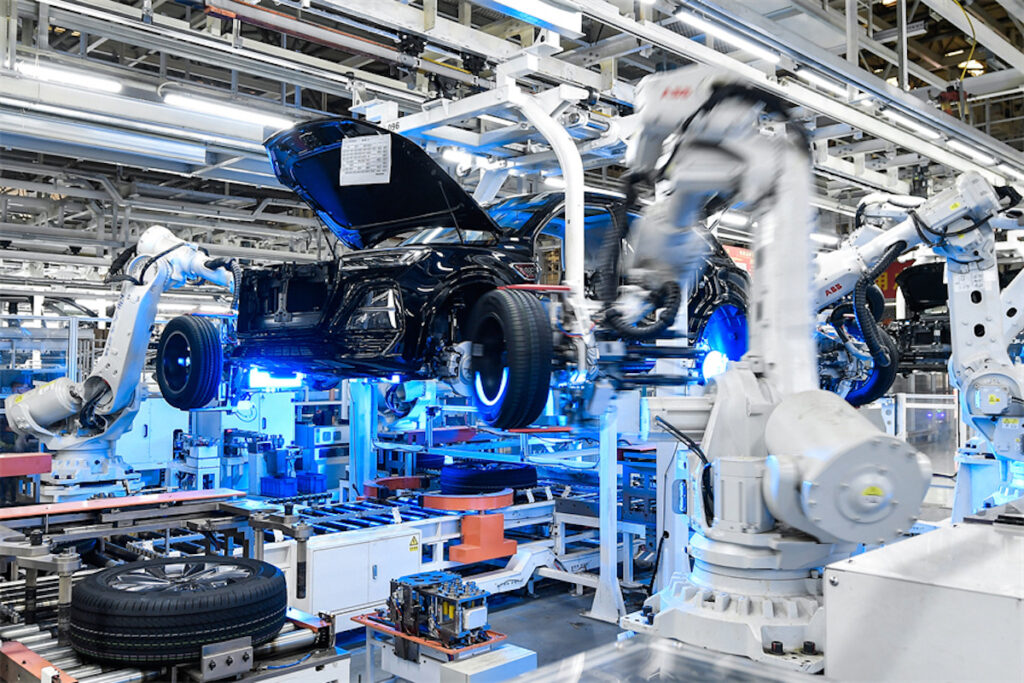

The Second China Shock is driven by China’s aggressive industrial policy, aimed at revitalizing its economy following a prolonged real estate downturn that began in late 2021. As domestic consumption remains weak, Chinese companies are exporting a surplus of goods, including electric vehicles and machinery, at competitive prices. This has resulted in a significant trade deficit for Europe with China.

The Economic Impact of China’s Export Strategy

Several factors are amplifying the impact of Chinese exports on Europe. A depreciating Chinese currency, due to both economic conditions and deliberate government actions, has made Chinese goods more affordable on the global market. According to a Shanghai Macro Strategist, this currency devaluation has created a situation where Chinese goods are extraordinarily cheap, making it difficult for other countries to compete.

“A night at the Four Seasons Beijing costs roughly US$250, compared with more than $1,160 in New York. The price gap is so extreme that it no longer reflects relative productivity or income levels; it reflects a currency that has become fundamentally undervalued.”

Additionally, changes in U.S. trade policy under the Trump administration, such as the end of the “de minimis” exemption for small packages, have redirected Chinese exports away from the U.S. and towards other markets, including Europe. Despite claims of transshipment to the U.S., experts like Gerard DiPippo assert that China has simply found new customers in Europe and beyond.

Why Europe Must Address the Second China Shock

While the influx of affordable Chinese goods might seem beneficial to European consumers, the long-term implications are concerning. The Economist recently suggested that Europe should embrace this shift, focusing on services rather than manufacturing. However, this perspective overlooks critical strategic and economic factors.

Military and Economic Considerations

From a military standpoint, Europe’s reliance on imported goods could undermine its defense capabilities. With Russia’s military ambitions and China’s support for Russian manufacturing, Europe must bolster its own industrial base to ensure readiness for potential conflicts. This requires maintaining a robust manufacturing sector that can be repurposed for defense needs if necessary.

Economically, Europe’s trade imbalance with China poses significant risks. As Robin Harding of the Financial Times warns, Europe is essentially writing IOUs to China, accumulating debt that must eventually be repaid. This unbalanced trade dynamic could weaken Europe’s financial stability over time.

“There is nothing that China wants to import, nothing it does not believe it can make better and cheaper, nothing for which it wants to rely on foreigners a single day longer than it has to.”

Innovation and Industrial Capacity

Furthermore, the loss of manufacturing jobs and expertise could stifle innovation in Europe. Manufacturing fosters “learning by doing,” a process that drives productivity and technological advancements. As economists David Autor and Gordon Hanson argue, China’s dominance in high-tech sectors could erode Europe’s innovative capacity, leaving it economically disadvantaged.

Strategies for Europe to Counter the Second China Shock

To mitigate these risks, Europe must consider a combination of competitive reforms and strategic protectionism. Robin Harding suggests that Europe needs to enhance its competitiveness through reforms, while also considering protective measures to shield its industries from Chinese competition.

“The difficult solution is for Europe to become more competitive and find new sources of value…Which leads to the bad solution: protectionism. It is now increasingly hard to see how Europe, in particular, can avoid large-scale protection if it is to retain any industry at all.”

Protectionism, in the form of tariffs and non-tariff barriers, could provide a buffer for European manufacturers, encouraging investment and innovation. Additionally, export subsidies could help European companies maintain their presence in global markets.

Another approach involves encouraging joint ventures between Chinese and European companies, allowing knowledge transfer and capacity building within Europe. Addressing China’s undervalued currency is also crucial, as it distorts global trade dynamics.

Looking Ahead: Building a Resilient European Economy

While the path forward is challenging, these measures could pave the way for a more balanced and sustainable global economy. By resisting the Second China Shock, Europe can preserve its industrial base, enhance its strategic autonomy, and secure its economic future.

Ultimately, Europe’s response to this challenge will shape not only its own economic landscape but also the broader global trade environment. As the continent navigates this complex issue, it must balance immediate economic benefits with long-term strategic interests.