Disruptions to our circadian clocks, the internal molecular timekeepers present in nearly every cell of our body, can lead to a wide range of health problems, from sleep disturbances to diabetes and cancer. However, the substances within the body that can shift these clocks and potentially cause such disruptions have remained uncertain—until now.

A groundbreaking study from Professor Gad Asher’s lab at the Weizmann Institute of Science, published in Nature Communications, reveals that sex hormones play a central role in aligning cellular clocks with one another and with the environment. The research team, led by Drs. Gal Manella, Saar Ezagouri, and Nityanand Bolshette, demonstrated that female sex hormones—particularly progesterone—alongside the stress hormone cortisol, have a significant impact on these clocks.

The Role of Blood-Borne Signals

It has been established that circadian clocks are influenced by external signals such as sunlight and by signals carried through the bloodstream. Until recently, these blood-borne signals had not been fully mapped, and the component within the clock that serves as their “point of entry” was not clearly identified. The challenge lay in the lack of a precise method for tracking the clock’s response to various signals over a complete 24-hour cycle.

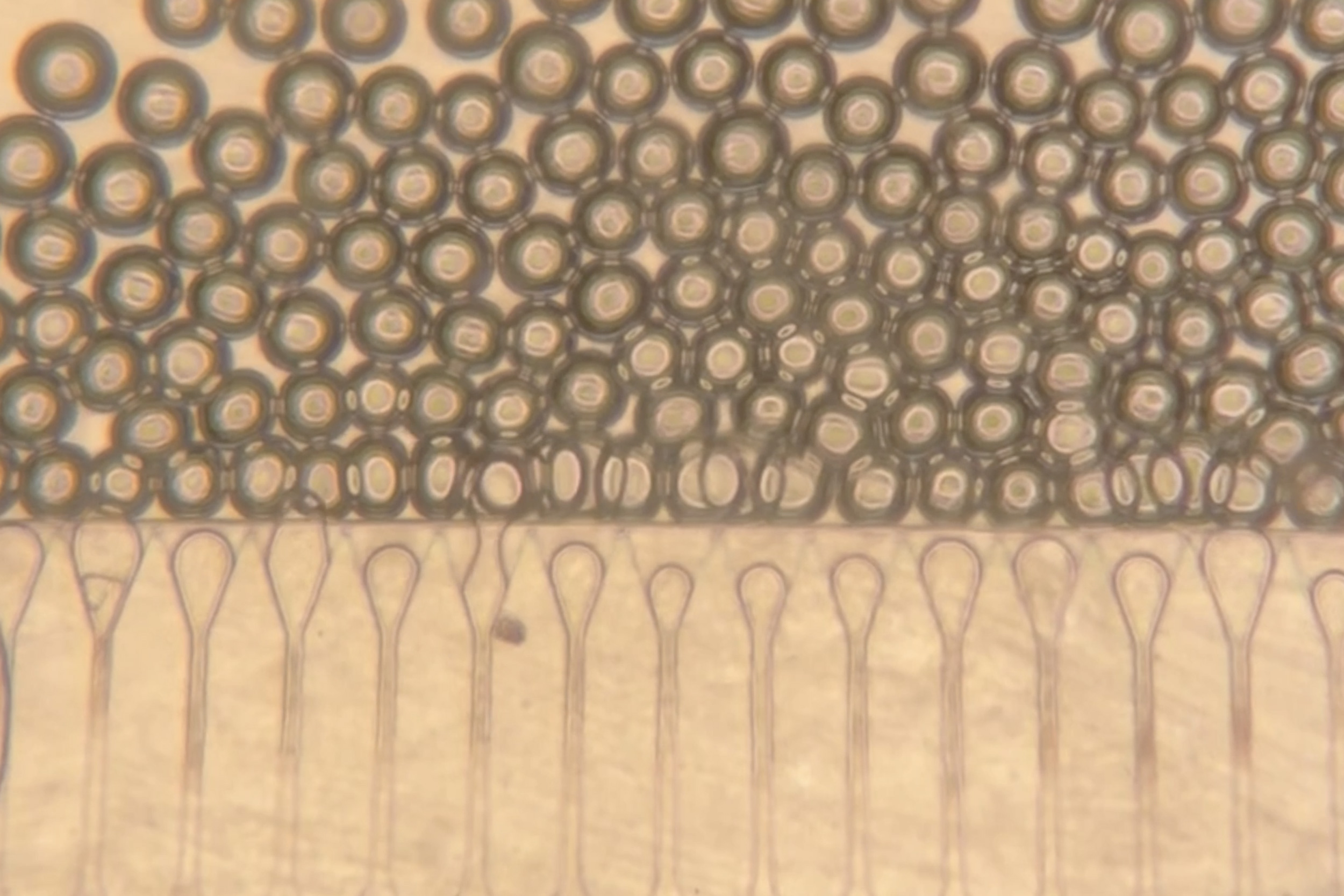

In recent years, Prof. Asher’s lab, a leader in the study of molecular mechanisms of circadian clocks, developed an innovative method using an array of human cells, each representing a different “time of day.” This approach is akin to a wall lined with clocks displaying the current time in major cities worldwide. This new method allowed researchers, for the first time and with unprecedented precision, to map how cellular clocks are synchronized by blood-borne signals.

Uncovering the Mechanisms

In addition to highlighting the influence of sex hormones, the study identified that the clock component receiving these signals is the protein Cry2, rather than Per2, as was previously believed. This discovery marks a significant shift in understanding the molecular interactions that govern circadian rhythms.

“The levels of sex hormones change throughout life—during menstrual cycles, pregnancy, hormone therapy, contraceptive use, and various disease states. These conditions are also known to be associated with disturbances to circadian clocks,” Asher notes. “Our new findings suggest that these disturbances are linked to interactions between sex hormones and the mechanisms that synchronize circadian clocks.”

Implications for Health and Medicine

The implications of these findings are vast, potentially affecting how we understand and treat various health conditions linked to circadian disruptions. For instance, hormonal changes during menopause or pregnancy could be better managed by considering their effects on the body’s internal clocks. Furthermore, this research could lead to new treatments for sleep disorders and metabolic diseases, offering a more personalized approach to medicine.

According to experts, this study opens new avenues for research into how hormonal therapies might be optimized to minimize their impact on circadian rhythms. The ability to precisely map and understand these interactions could lead to breakthroughs in managing conditions like shift work disorder and jet lag, which are exacerbated by circadian misalignment.

Looking Ahead

The study’s findings underscore the importance of further research into the molecular underpinnings of circadian clocks and their interaction with hormones. As researchers continue to explore these pathways, the potential for new therapeutic strategies grows, promising improved health outcomes for individuals affected by circadian disruptions.

As the scientific community delves deeper into the complexities of our internal timekeepers, the hope is that these insights will pave the way for innovative solutions to some of the most persistent health challenges of our time.