Seals, along with many other mammals, have a remarkable ability to delay pregnancy until environmental conditions are optimal. This phenomenon, known as embryonic diapause, allows a female seal to pause the implantation of an embryo in the uterine wall until her body is ready to support the pregnancy. This strategy is not unique to seals; it is practiced by hundreds of mammals, from mice to moose. The question that arises is: how does an embryo, designed to follow a strict developmental timeline, manage to halt and then restart its growth seamlessly?

A recent study published in Genes & Development sheds light on this mystery. The research reveals how diapaused embryonic stem cells in mice maintain their pluripotency—the ability to become any cell type. The study found that these cells activate a molecular program that effectively switches off pathways that normally drive cell differentiation. This discovery not only explains how embryos survive diapause but also provides insights into how certain immune cells and even cancer cells endure prolonged periods of metabolic stress.

Arrested Development: A Widespread Phenomenon

Embryonic diapause is a common survival strategy across the animal kingdom, employed by mammals, fish, insects, and many species. In mammals, development typically pauses at the blastocyst stage shortly after fertilization. The blastocyst, a ball of a few hundred cells, remains in a state of suspended animation until conditions improve, at which point it implants in the uterine wall and resumes normal development.

Previous studies have demonstrated that embryonic stem cells can enter a diapause-like state in laboratory settings when exposed to various stressors. For instance, blocking mTOR, a key regulator of cellular growth and metabolism, can induce this state by shutting down pathways responsible for protein synthesis. Similarly, reducing Myc family transcription factors or altering chromatin regulators like MOF can push cells into a low-energy mode. These findings suggest that diapause is a protective default state that can be triggered by diverse forms of stress.

“Diapause appears to be a state that can be reached in many different ways and due to many different kinds of harsh circumstances,” explains Alexander Tarakhovsky, head of the Laboratory of Immune Cell Epigenetics and Signaling.

Tarakhovsky’s team aimed to understand the mechanisms that preserve a cell’s identity and flexibility during this suspended animation. They identified a transcriptional program that maintains stem cell pluripotency even under stress.

The Molecular Brake: A Key Discovery

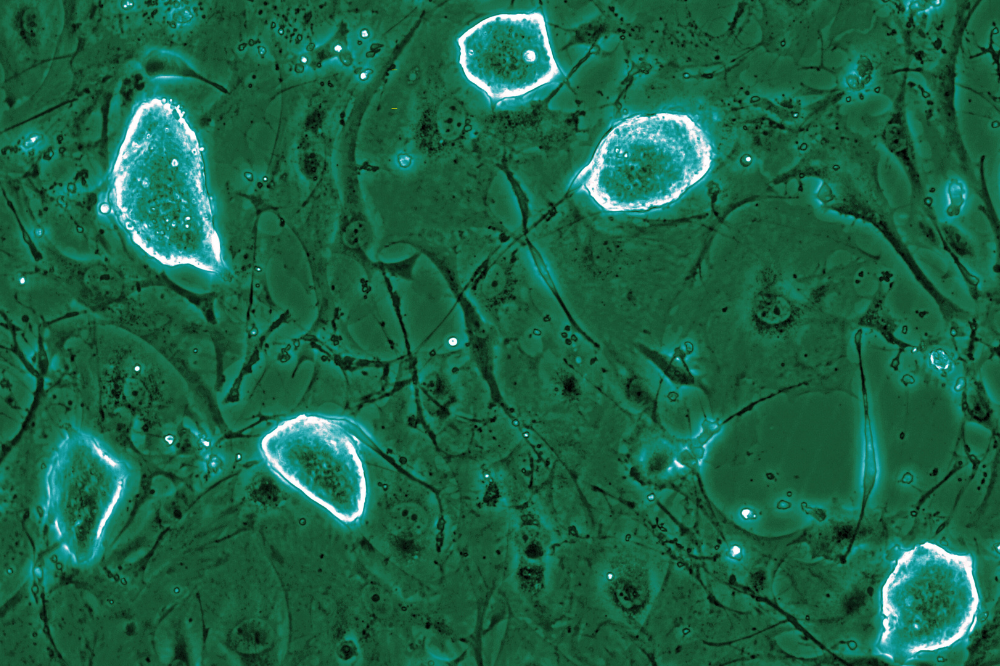

The researchers induced a diapause-like state in murine embryonic stem cells using I-BET151, a BET inhibitor developed in their lab that mimics Myc deficiency. They also employed mTOR inhibition to simulate the metabolic slowdown caused by nutrient scarcity. In both scenarios, the cells remained pluripotent while significantly reducing their metabolism, RNA production, and protein synthesis. Remarkably, these cells stayed in this suspended state even when researchers attempted to push them toward specialized cell fates. Once the inhibitors were removed, the cells resumed normal development and could contribute to healthy embryos.

Further examination revealed that all stressors—mTOR inhibition, BET inhibition, and Myc loss—triggered the same core response. The cells activated a set of genes that act as natural brakes on the MAP kinase pathway, which typically drives stem cells to commit to specific fates. When researchers turned off these “brakes,” the cells quickly lost their pluripotency and began differentiating, confirming the braking system’s essential role in maintaining the diapause-like state.

The stressors displaced a protein called Capicua, which normally represses these genes. Removing Capicua allowed the brake genes to activate, revealing a molecular switch that keeps cells paused yet poised during suspended animation.

Implications for Human Health

This discovery of a molecular mechanism that allows stem cells to retain their identity during dormancy has significant implications. It supports the view of diapause as a state arising from the network’s structure rather than any single regulator. The findings build on the Tarakhovsky lab’s expertise in epigenetic control, including their pioneering work in histone mimicry.

The implications extend beyond embryos. Many cell types survive by reducing their metabolism for extended periods, and this molecular brake may help explain how immune cells persist for decades, how stem cells in tissues maintain their identities under stress, and how certain viruses and cancer cells can remain dormant before reactivating. The team is also investigating whether diapause-like programs influence neuron aging or damage resistance.

“Humans don’t experience diapause—we aren’t hibernating like bears, and our embryos don’t enter suspended animation under stress—but there are cells in our bodies that do,” Tarakhovsky notes. “With studies like these, we’re hoping to gain insight into the general principles that explain the cell dormancies that impact human health.”

Ultimately, this research positions diapause as a powerful model for understanding how organisms and cells endure deep metabolic stress, providing a framework for exploring dormancy across biology.