Knots are ubiquitous, appearing in everything from tangled headphones to DNA strands within viruses. Yet, the mystery of how an isolated filament can knot itself without collisions or external agitation has puzzled soft-matter physicists for years. Now, researchers from Rice University, Georgetown University, and the University of Trento in Italy have discovered a surprising mechanism that explains how a single filament can form a knot while sinking through a fluid under strong gravitational forces. This breakthrough, published in Physical Review Letters, offers new insights into polymer dynamics, influencing fields from DNA behavior to the design of advanced soft materials and nanostructures.

“It is inherently difficult for a single, isolated filament to knot on its own,” explained Sibani Lisa Biswal, corresponding author and chair of Rice’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. “What’s remarkable about this study is that it shows a surprisingly simple and elegant mechanism that allows a filament to form a knot purely because of stochastic forces as it sediments through a fluid under strong gravitational forces.”

Unraveling the Knotting Mechanism

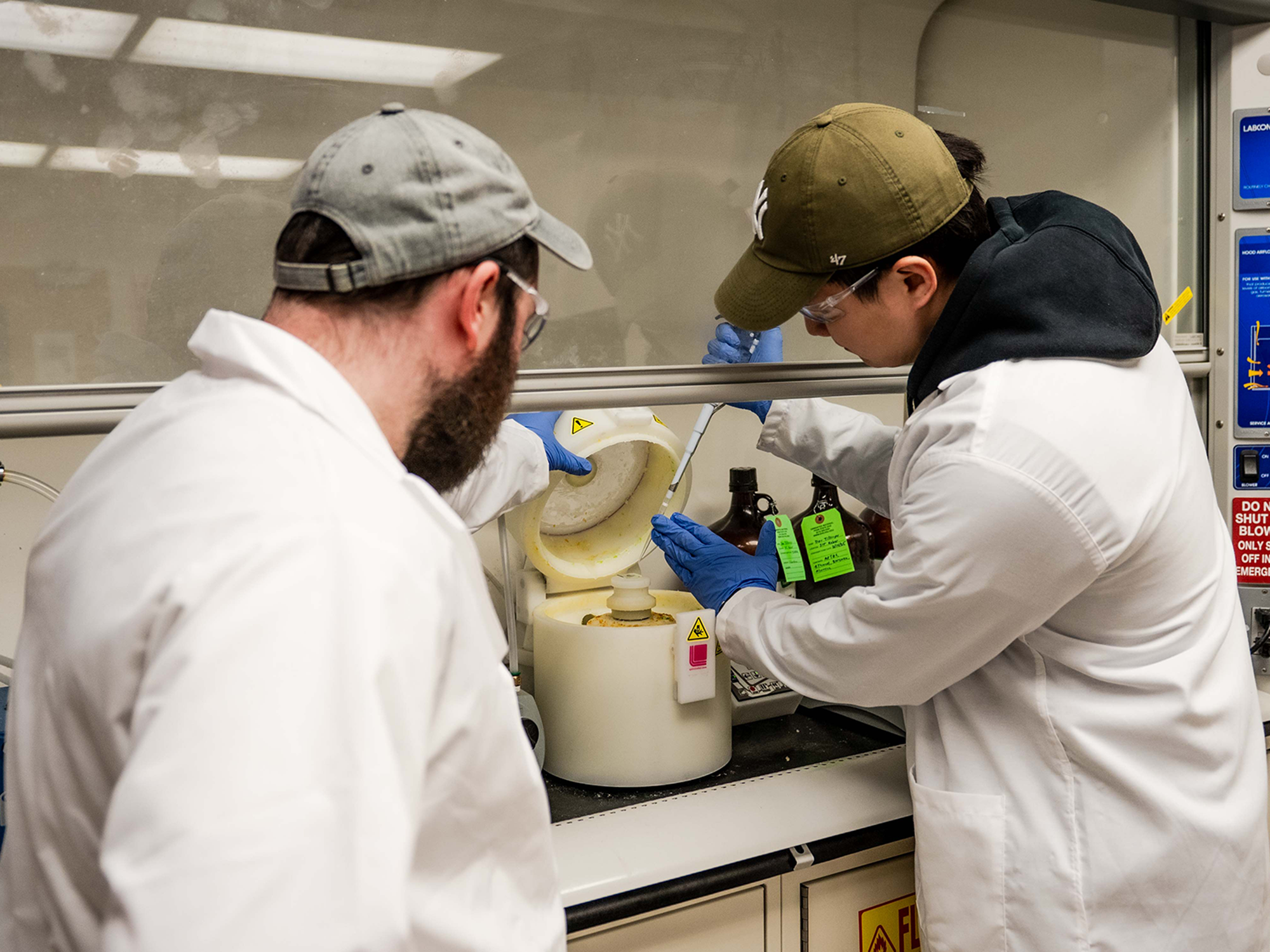

Using Brownian dynamics simulations, the research team demonstrated that as a semiflexible filament falls through a viscous fluid, akin to conditions in ultracentrifugation, long-range hydrodynamic flows can bend and fold the filament onto itself. These flows concentrate part of the filament into a compact head while stretching the remainder into a trailing tail, creating a configuration that allows loops to cross and lock into stable knots.

“We found that these knots don’t just appear, but rather they evolve through a dynamic hierarchy, tightening and reorganizing into more stable topologies, almost like an annealing process,” said Fred MacKintosh, co-corresponding author and professor at Rice University.

The simulations revealed that stronger gravitational fields increase both the likelihood and stability of knot formation. More flexible filaments more easily form a wide range of knot types. At high field strengths, the knots persist for long periods, stabilized by tension within the filament due to hydrodynamics and friction between segments, allowing the system to reach intricate and long-lived configurations.

Implications for Biology and Materials Science

The knotting of polymers plays a critical role in biological systems. Proteins and other macromolecules can form knots that influence their behavior and function inside cells. In some cases, they are beneficial, while in others, like genomic DNA, they can be detrimental. Understanding how these knots form and stabilize provides a new foundation for interpreting processes such as genome packaging, electrophoresis, and nanopore transport.

“This study deepens our understanding of how forces and flows shape polymer behavior,” Biswal noted. “It opens the door to designing new materials whose mechanical properties are programmed by their topology and not just their composition.”

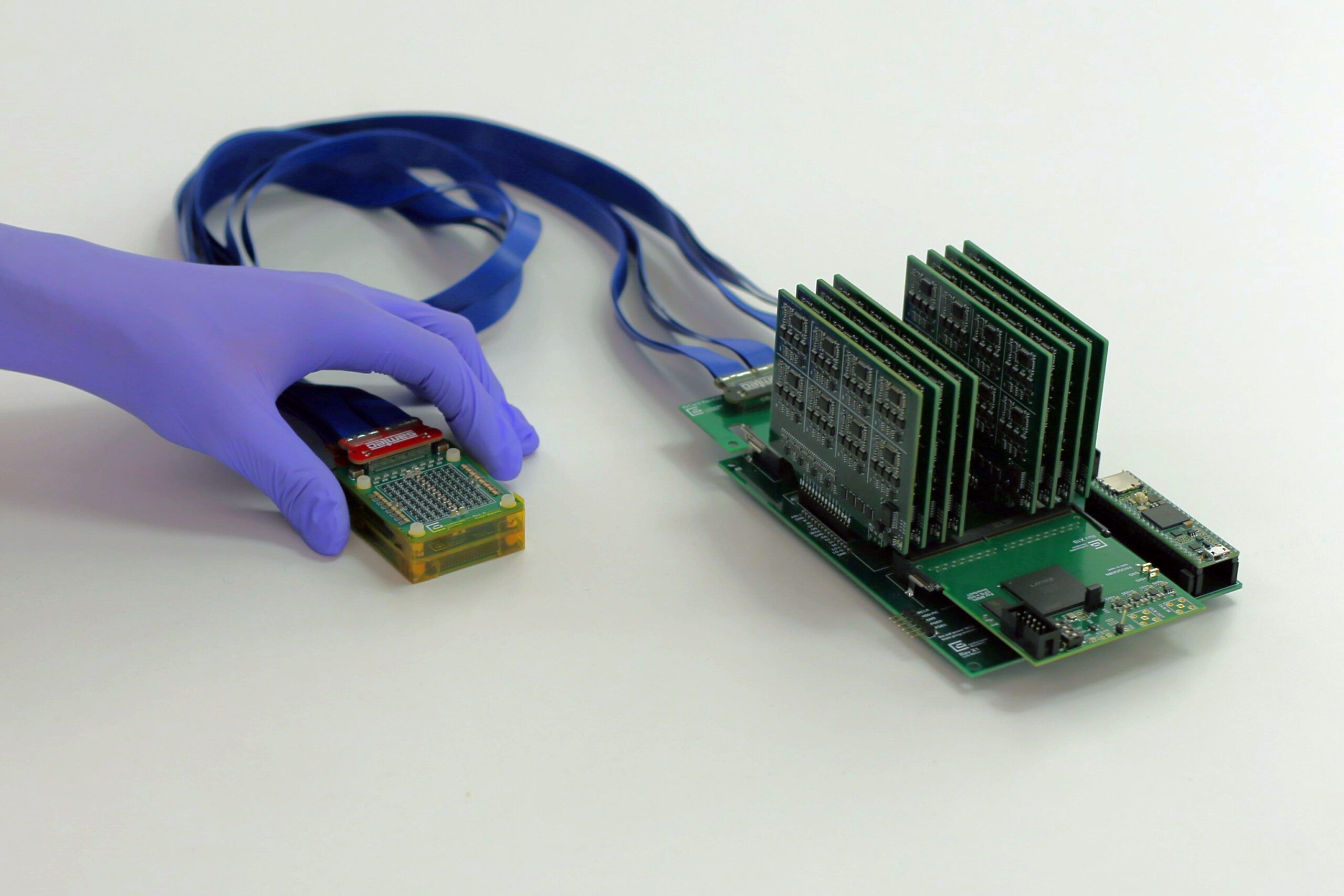

Beyond biology, these findings could inform emerging approaches to nanomaterials fabrication, where controlling knotting could lead to patterned or mechanically reinforced structures. It may also offer insight into improving large-scale separation and characterization tools used in laboratories and industry.

“Field-driven knotting may someday provide a scalable alternative to what researchers currently call ‘knot factories,'” MacKintosh said. “By learning how to harness this natural process, we can imagine new technologies that leverage hydrodynamics and self-assembly instead of manual or chemical manipulation.”

Future Directions and Potential

This research opens new possibilities for creating long-lived, tight, complex knots in very short polymers, bridging the gap between knot theory and polymer theory predictions with experimental observations. Luca Tubiana, co-author and associate professor at the University of Trento, emphasized the significance of this achievement, noting the potential for better connecting theoretical predictions with practical experiments.

“In general, knots appear in very long polymers and require even longer polymers to become tight and stable,” Tubiana explained. “Our study suggests an experimentally achievable way to obtain long-lived, tight, complex knots in very short polymers.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation Divisions of Materials Research, Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, and Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships. As scientists continue to explore the implications of these findings, the potential for innovative applications in both biological and material sciences remains vast.