Far beneath the Black Hills of South Dakota, a tank of liquid xenon is quietly recording some of the faintest signals in the universe. In that deep, quiet space, researchers have pushed their instrument to do two jobs at once. It has tightened the net around one possible form of light dark matter and, at the same time, captured strong evidence of rare scattering from neutrinos produced in the sun.

The experiment, called LUX-ZEPLIN, or LZ, sits nearly a mile underground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility. The collaboration includes about 250 scientists and engineers from 37 institutions, managed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. With its latest analysis, the team used 417 live days of data, corresponding to 5.7 tonne-years of exposure, to search for weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs, with masses between 3 and 9 gigaelectronvolts, and to study solar neutrinos.

Challenging the Darkness: The Search for WIMPs

Dark matter does not emit light and rarely interacts with ordinary matter, yet its gravitational influence helps shape galaxies and holds the cosmos together. The idea behind WIMPs is that, occasionally, one of these particles might collide with a xenon nucleus inside the detector, leaving a faint trace of energy.

In this latest run, the team found no sign of WIMPs in the low mass range. However, the data set new world-leading limits on how often such particles could interact with nuclei for masses above about 5 gigaelectronvolts. Simultaneously, the detector picked up signals from solar neutrinos through a process called coherent elastic neutrino nucleus scattering, with a statistical significance of 4.5 sigma, indicating clear evidence.

Exploring the Neutrino Fog

When picturing a WIMP as a ghostly billiard ball, lighter versions have less impact upon colliding with a xenon atom. These interactions produce nuclear recoils with very low energy, often just a few thousandths of a volt at the atomic scale, challenging even the most sensitive detectors.

LZ had already set the strongest constraints on WIMPs heavier than 9 gigaelectronvolts. Extending the search down to 3 gigaelectronvolts meant delving into a range where the signal blends with cosmic background noise. Neutrinos from the sun, especially those from boron-8 decays, can strike xenon nuclei similarly to light dark matter particles of about 5.5 gigaelectronvolts, creating what is often called the “neutrino fog.”

Other xenon-based detectors, such as PandaX-4T and XENONnT, had reported hints of this boron-8 scattering at below the usual discovery threshold, reaching around 3 sigma significance or less.

LZ improves on these results using more exposure, better calibrations, and a search region tuned to the lowest detectable nuclear recoil energies. This means the search for light dark matter is no longer isolated from neutrino physics, as detectors at this sensitivity inevitably detect neutrinos too.

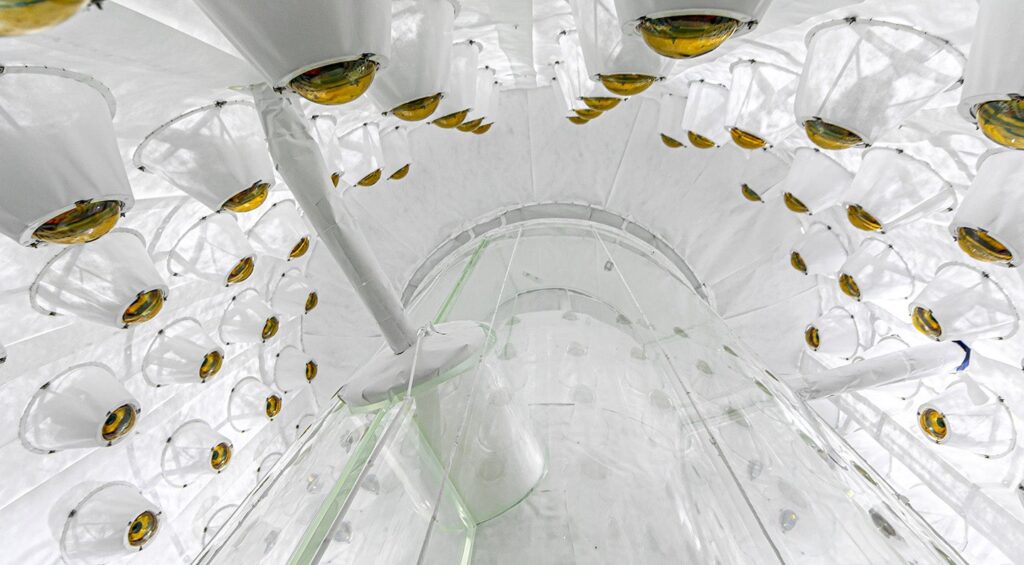

The Inner Workings of the Underground Xenon Eye

At the heart of LZ is a dual-phase time projection chamber holding about 7 tonnes of liquid xenon. Additional xenon in surrounding layers, called the Skin, and an Outer Detector of organic scintillator help veto unwanted radiation. This entire setup is housed within a large tank containing approximately 230 tonnes of ultrapure water to block cosmic rays and other background particles.

When any particle interacts in the liquid xenon, it can create a brief flash of ultraviolet light and knock loose electrons. Sensors above and below the chamber, arrays of photomultiplier tubes, record both signals. The first flash, called S1, occurs almost instantly. The freed electrons drift upward in an electric field, creating a second flash, S2, upon reaching a thin layer of xenon gas near the top.

By measuring the time between S1 and S2, the team can determine the depth of the interaction. The light’s spread across the upper sensor array reveals the horizontal position, resulting in a three-dimensional map of each event. This allows the analysis to focus on a central “fiducial volume” of xenon, well shielded from radioactive backgrounds near the walls.

Sifting Rare Signals from Noise

To detect possible dark matter and neutrino interactions, the analysis focused on “single scatter” events showing exactly one S1 signal and one S2 signal. The trigger system efficiently detects very small S2 pulses, corresponding to just a few extracted electrons. However, requiring at least three photomultiplier tubes to see the initial S1 flash reduces efficiency at the lowest energies. The team used simulations and calibration sources, including tritiated methane, to measure and correct for these losses.

They also tracked how the detector response changed with position and time. Alpha decays from naturally occurring radon daughters spread through the xenon helped calibrate these variations. The result is a set of corrected observables, called S1c and S2c, expressed in photons detected. For this study, the region of interest included S1c between 2 and 15 photons and S2 values corresponding to about 3.5 to 14.5 extracted electrons, matching nuclear recoil energies between roughly 1 and 6 kiloelectronvolts.

To ensure data quality, the collaboration removed data for a time period that grows with the size of earlier events to avoid delayed light emissions or trapped electrons mimicking real events. This choice sacrificed about 16% of the total exposure but resulted in a much cleaner final sample. Periods with unstable conditions or high sensor noise were also removed, leaving 417 high-quality live days.

What the Detector Actually Saw

In the end, after all cuts and the removal of one fake event inserted for bias checks, 19 events remained in the region of interest. The biggest remaining background came from “accidental coincidences,” where an unconnected S1 and S2 pulse align in the same analysis window. These can result from random sensor dark counts or stray electrons drifting off metal surfaces.

The team modeled these accidentals by pairing real isolated S1 and S2 signals according to measured photon and electron rates. They validated this model against several data samples, including events with impossible drift times known to be accidental. In the final search window, the model predicted about 6.6 such background events, with a small uncertainty, along with roughly 20.6 events from boron-8 neutrinos and a negligible number from detector neutrons.

The collaboration used an unbinned profile likelihood analysis in the space of S1c and S2c to compare these expectations to the data, setting new upper limits on the spin-independent scattering rate between dark matter and nucleons.

At a mass of 3 gigaelectronvolts, the limit is around 2.9 × 10⁻⁴² square centimeters. By 9 gigaelectronvolts, the limit improves to about 1.2 × 10⁻⁴⁶ square centimeters, making these results the most sensitive yet in much of that low mass range.

Entering the Neutrino Fog

Within the framework of the Standard Model of particle physics, the analysis can be translated into a measurement of how many boron-8 neutrinos reach the detector and how strongly they scatter from xenon nuclei. The best fit boron-8 neutrino flux is on the order of 3.1 million per square centimeter per second, compatible with earlier solar measurements once uncertainties are included.

Viewed differently, if you take the expected solar flux from previous experiments as given, the LZ data imply a flux-weighted scattering cross-section for neutrinos on xenon of about 7.4 × 10⁻⁴⁰ square centimeters, close to the predicted value of roughly 1.2 × 10⁻³⁹. Interpreted in terms of the weak mixing angle, a quantity that controls how particles feel the weak force, the result, sin²θ_W ≈ 0.16 with sizable error bars, sits comfortably near the Standard Model curve.

Researchers involved in the analysis say this agreement is an important check. “This result is clear confirmation that LZ could observe even low-mass dark matter,” said Scott Kravitz, assistant professor at The University of Texas at Austin and analysis coordinator for LZ. “It’s particularly powerful to look at something fully out of our control, nuclear fusion from the sun, and find that the predicted rate of events from that process is consistent with our observations. It means the detector and our experiment are as sensitive as expected, and capable of finding dark matter if it’s within the range where we’re searching.”

Ann Wang, associate staff scientist at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and co-lead of the study, emphasized how this background shapes future searches. “With this dataset, we have officially entered the neutrino fog, but only when searching for dark matter with these smaller masses,” Wang said. “If dark matter is heavier, say, 100 times the mass of a proton, we’re still far away from neutrinos being a significant background, and our discovery power there is unaffected.”

Looking Ahead to Bigger Detectors

The LZ collaboration plans to collect more than 1,000 days of live search data by 2028, more than doubling the present exposure. With that larger sample, sharper limits on heavier WIMPs in the 100 gigaelectronvolt to 100 teraelectronvolt range are expected. The team also aims to lower the energy threshold further, allowing them to probe dark matter masses below 3 gigaelectronvolts and explore unusual interaction types that do not fit the simplest models.

Beyond WIMPs and solar neutrinos, the detector already has the sensitivity to look for a range of rare phenomena. These include millicharged particles with tiny electric charges, dark matter particles boosted by cosmic rays, solar axions, and exotic neutrino interactions with electrons. “We are in discovery territory, and there is a large swath of physics phenomena that LZ can now access with greater sensitivity,” said Alvine Kamaha, assistant professor at UCLA and chair of LZ’s institutional board.

Many members of the collaboration are also working on designs for a next-generation xenon detector, known as XLZD. That instrument would combine the strongest features of LZ, XENONnT, and DARWIN and use an even larger xenon mass. It would function as a dark matter observatory and a precision neutrino lab, able to study the sun, supernova explosions, cosmic rays, and other possible dark sector particles like dark photons and axion-like particles.

“As with so much of science, it can take many deliberate steps before you reach a discovery, and it’s remarkable to realize how far we’ve come,” said Rick Gaitskell, a professor at Brown University and the spokesperson for LZ. “Our latest detector is over 3 million times more sensitive than the ones I used when I started working in this field.”

Practical Implications of the Research

Although this work takes place in a remote underground lab, its impact reaches far beyond the Black Hills. By ruling out broad ranges of WIMP masses and interaction strengths, the LZ results guide theory toward models of dark matter that better match reality. That focus helps researchers avoid investing time and resources in ideas that the data already exclude.

The new evidence for coherent scattering of solar neutrinos on xenon provides an independent way to check how the sun burns and how neutrinos behave. Over time, precise measurements of neutrino flux and scattering may reveal subtle deviations from the Standard Model, which could point to new physics. These breakthroughs often ripple outward, shaping technologies in fields such as medical imaging, nuclear security, and radiation detection.

As LZ and future detectors approach the limits set by the neutrino fog, they will also sharpen knowledge of fundamental constants like the weak mixing angle. Better values for these parameters feed into simulations of stars, the early universe, and nuclear processes that underlie everything from power generation to national security.

Finally, projects like LZ and the planned XLZD detector train large teams of scientists and engineers in advanced cryogenics, sensor technology, data analysis, and ultra-low background construction. Those skills translate into innovations in computing, materials, and instrumentation that can benefit medicine, industry, and environmental monitoring, even if dark matter itself remains hidden for a while longer.

Research findings are available online in the journal lz.lbl.gov.