It’s a concept straight out of science fiction: being declared legally dead, having your body frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then being revived centuries later. This is the promise of cryonics, a controversial field that has long captured the imagination and skepticism of many. At the Southern Cryonics facility near Holbrook, NSW, Peter Tsolakides is among those who believe cryonics could be humanity’s future.

The idea of a second chance at life, whether in 100, 200, or even 2000 years, remains speculative. However, Tsolakides points to advancements that have made the concept less far-fetched. Despite this, the practice of storing bodies at low temperatures in the hope of future revival faces significant skepticism from the scientific community.

The Science Behind Cryonics

University of Western Australia’s associate professor Marcus Dabner, a specialist in pathology, describes cryonics as unproven and speculative. He emphasizes that no one has been successfully revived from cryonic preservation anywhere in the world. Nevertheless, the idea persists, fueled by stories like that of Clare McCann, an Australian journalist who sought to cryonically preserve her son after his tragic death.

McCann’s story highlights the emotional and financial stakes involved. Her plea to raise $300,000 for her son’s preservation underscores the faith some place in cryonics, despite its uncertain outcomes. Facilities across the globe, including those in the US, Russia, China, Australia, and Europe, continue to offer cryonic services.

Ethical and Financial Considerations

Critics argue that cryonics offers false hope, exploiting vulnerable individuals consumed by grief. The cost of cryonic suspension in Australia ranges from $150,000 to $200,000, excluding potential future revival costs. Clive Coen, a neuroscience professor at King’s College London, warns of the ethical complexities, suggesting that cryonics may lead people to believe it’s worth the gamble.

Peter Tsolakides acknowledges these concerns, stating that Southern Cryonics does not promise future revival. The facility caters to individuals with a longstanding interest in cryonics, aiming to avoid exploiting those in distress. Tsolakides notes that many members use life insurance to fund their preservation and plan financially for potential revival.

Legal Implications

Dr. Kate Falconer from the University of Queensland highlights potential legal challenges if revival becomes possible. Currently, deceased individuals cannot own property, and their estates are distributed according to their wills. This could create “cryonics refugees” — individuals revived without social ties or financial resources. Some cryonics facilities encourage placing assets in long-term trusts to mitigate this issue.

Scientific Challenges and Progress

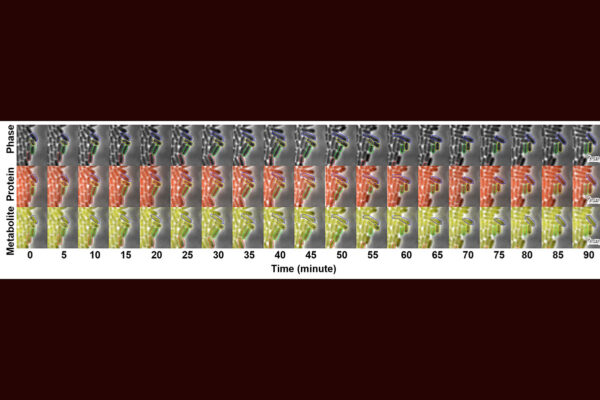

Cryonics enthusiasts draw optimism from scientific research, such as the successful cryopreservation and revival of simple organisms like roundworms. They also cite experiments where organs, such as rabbit kidneys, were preserved and later transplanted. However, Dr. Dabner cautions that no complex organisms, particularly mammals, have been successfully revived.

The preservation of the brain remains a significant hurdle. Tsolakides hopes advancements in nanotechnology and regenerative medicine will eventually solve this challenge. The process of vitrification, which replaces blood with a cryoprotectant to prevent ice formation, is crucial for preserving the body until future medical advancements can potentially restore health.

The Future of Cryonics

Despite the hurdles, Tsolakides remains optimistic about the future of cryonics. He believes that ongoing research in brain preservation, hypothermic medicine, and other fields will eventually make revival feasible. For now, Southern Cryonics focuses on maintaining the best possible conditions for preservation.

Dr. Dabner remains skeptical, viewing cryonics as largely science fiction. He emphasizes the complexity of life and the numerous technical challenges that must be overcome. He suggests that existing methods of contributing to science and society after death, such as organ donation, offer more tangible benefits.

As for Tsolakides, he plans to undergo cryopreservation himself, hopeful about the possibility of waking up in a future world. He sees cryonics as a third option beyond burial or cremation, offering a chance, however remote, of returning to life.

For those considering cryonics, the journey is one of hope, curiosity, and the belief in future scientific breakthroughs. Whether this vision will become reality remains to be seen, but the debate over cryonics continues to captivate and challenge our understanding of life and death.

Support Resources:

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

- Headspace: 1800 650 890

- Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636