The creation of “ultrablack” fabric, reflecting less than 0.5% of light, marks a significant breakthrough by researchers at Cornell University. This innovative material, inspired by the magnificent riflebird, offers potential applications in cameras, solar panels, and telescopes. The development, announced by the Responsive Apparel Design (RAD) Lab in the College of Human Ecology, promises a simple and scalable method for producing the elusive color.

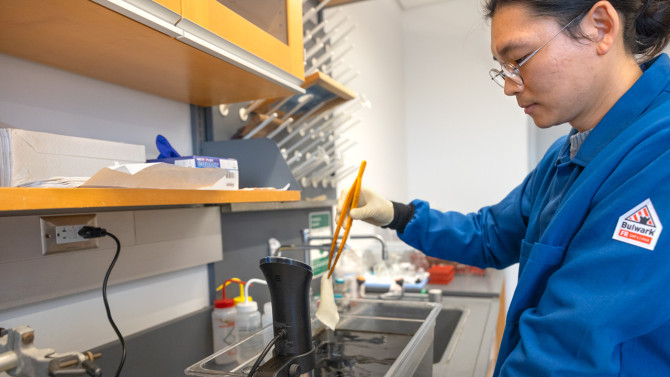

By studying the natural world, specifically the ultrablack feathers of the riflebird, researchers dyed white merino wool with polydopamine and etched it in a plasma chamber. This process created nanofibrils—spiky nanoscale growths—mimicking the light-trapping capabilities of the bird’s feathers. The result is the darkest fabric currently reported, which maintains its color regardless of viewing angle.

Nature’s Influence on Technological Innovation

The riflebird, a member of the bird-of-paradise family found in New Guinea and Australia, served as the primary inspiration for this research. Its feathers, with melanin pigment and tightly bunched barbules, absorb nearly all light, appearing extraordinarily black when viewed straight on. This natural phenomenon is also seen in other creatures like certain fish and butterflies.

Larissa Shepherd, assistant professor in the Department of Human Centered Design and senior author of the study, emphasized the importance of these natural structures. “Polydopamine is a synthetic melanin, and melanin is what these creatures have,” she explained. “The riflebird has these really interesting hierarchical structures, the barbules, along with the melanin. So we wanted to combine those aspects in a textile.”

The Science Behind Ultrablack Fabric

The researchers’ two-step approach involved ensuring the polydopamine penetrated the wool fibers completely. The plasma etching process then removed some surface material, leaving behind the crucial spiky nanofibrils. “The light basically bounces back and forth between the fibrils, instead of reflecting back out—that’s what creates the ultrablack effect,” explained Hansadi Jayamaha, a doctoral student and RAD Lab member.

Analysis revealed that the fabric had an average total reflectance of 0.13%, making it the darkest fabric yet reported. It remained ultrablack across a 120-degree angular span, superior to currently available commercial materials.

Potential Applications and Future Prospects

The ultrablack fabric’s potential extends beyond fashion. Kyuin Park, another RAD Lab member, noted its applications in solar thermal technologies. “We could actually use the ultrablack fabric for thermo-regulating camouflage,” he said, highlighting its versatility.

In a practical demonstration, Zoe Alvarez, a fashion design management major, created a black strapless dress incorporating the ultrablack material. The dress, accented with iridescent blue, showcased the fabric’s unique properties. When images of the dress were adjusted for contrast and brightness, the ultrablack sections remained unchanged, confirming its deep blackness.

Shepherd and her team have applied for provisional patent protection and are seeking to advance their innovation through Cornell’s Ignite Innovation Acceleration program. This step aims to bring their ultrablack fabric closer to commercial availability.

Conclusion

The development of ultrablack fabric represents a significant leap in material science, blending natural inspiration with cutting-edge technology. As the team moves forward with patent applications and potential commercialization, the implications for various industries—from fashion to renewable energy—are vast and promising.

Analysis of the material was conducted at the Cornell Center for Materials Research and Human Centered Design shared instrumentation facility, ensuring rigorous scientific validation of this groundbreaking innovation.