Summer has arrived in Australia, bringing with it an influx of mosquitoes, especially after a particularly wet spring. As outdoor activities increase, the use of insect repellent becomes a staple for many. However, questions about the safety and necessity of these repellents continue to arise.

Mosquito bites are not just a minor nuisance; they can lead to significant health issues. While the initial reaction to a mosquito bite is often just itchiness and swelling, scratching can introduce infections, particularly in young children. More concerning, however, is the potential for mosquito-borne diseases, which pose a risk across much of Australia, including cooler regions like Victoria and Tasmania.

The Threat of Mosquito-Borne Diseases

Mosquito-borne diseases in Australia can range from mildly irritating to severely debilitating. While there are no specific cures for many of these diseases, prevention remains the best strategy. Vaccines are available for some, like Japanese encephalitis, but others, such as Ross River virus and Murray Valley encephalitis, require proactive measures to avoid bites.

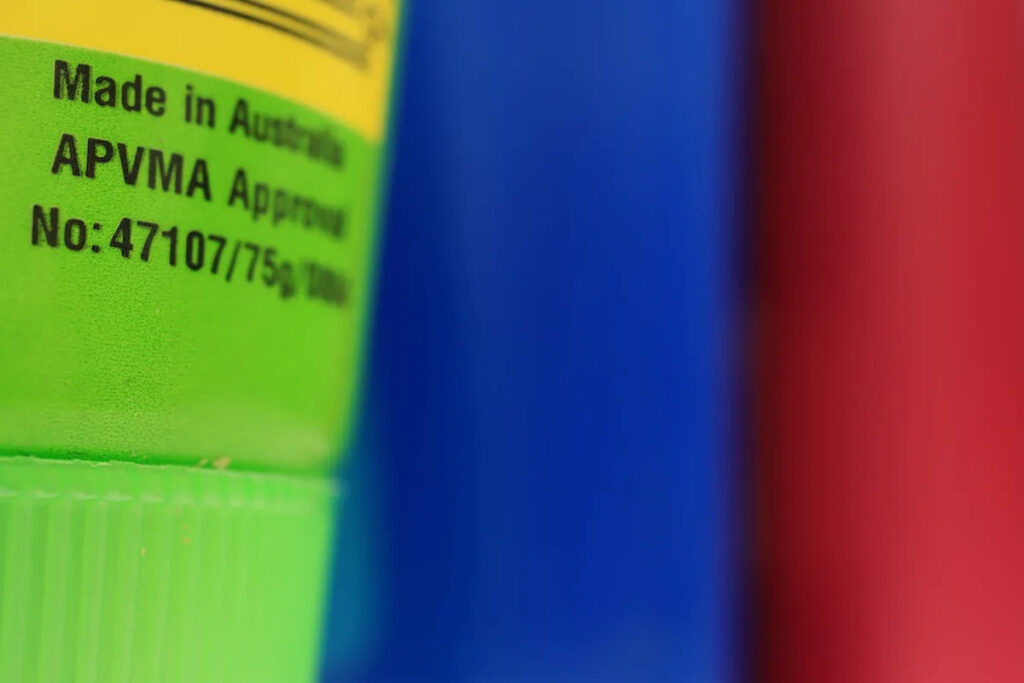

Australian health authorities frequently update guidelines on insect repellent usage, reflecting the variety of products available each summer. The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) plays a crucial role in assessing these products for safety and efficacy, ensuring that packaging includes necessary safety information and usage directions.

Understanding Mosquito Repellents

The most common active ingredients in mosquito repellents are diethyltoluamide (DEET), picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE). Plant-derived alternatives, such as eucalyptus and tea tree oil, offer some protection but require more frequent application.

Despite some perceptions that repellents may be unpleasant or hazardous, research consistently shows they are safe and effective when used as directed. DEET, in particular, has been extensively studied, while picaridin and OLE, though newer, are also recommended by health authorities worldwide. Natural or DIY repellents, however, can pose risks, including skin reactions, if unregistered and untested.

Safety Considerations for Children

Most repellents in Australia are approved for use on children over 12 months, although not all products specify age restrictions. International studies support the safety of DEET and picaridin for children, though recommendations can vary by country. In the U.S., for example, DEET has no age limit, while OLE is advised only for children over three.

A 2024 study concluded DEET is the preferred repellent for children, offering long-lasting protection when used correctly.

Parents should adhere to APVMA guidelines, applying repellent to their hands before rubbing it onto a child’s skin, and avoiding direct application to the face. It’s crucial to prevent children from applying repellent themselves to avoid accidental ingestion.

Alternative Protection Methods

For infants and toddlers, using insect nets on strollers or playpens can provide additional protection. Products like wristbands and patches are marketed for children but lack strong evidence of effectiveness. Likewise, smouldering devices like coils are discouraged due to potential smoke inhalation risks.

Effectiveness of Different Repellent Varieties

Unlike sunscreens, mosquito repellents lack a standardized measure of effectiveness. Terms like “heavy duty” or “tropical strength” often indicate higher concentrations of active ingredients, providing longer-lasting protection. Lower concentrations still work effectively but require more frequent application.

Proper application is key to maximizing protection. Whether using a cream, spray, or other form, ensuring complete coverage of exposed skin is essential. Reapplication is necessary after swimming, sweating, or if the repellent rubs off.

This article is republished from The Conversation. It was written by: Cameron Webb, University of Sydney

Cameron Webb and the Department of Medical Entomology, NSW Health Pathology and University of Sydney, have been engaged by a wide range of insect repellent and insecticide manufacturers to provide testing of products and provide expert advice on medically important arthropods, including mosquitoes. Cameron has also received funding from local, state, and federal agencies to undertake research into various aspects of mosquito and mosquito-borne disease management.