Particle physics stands at the frontier of understanding the universe’s most fundamental elements. By investigating the smallest particles and the forces that govern them, this field seeks to answer profound questions about the origins and structure of everything around us. From simulating the Big Bang with particle accelerators to exploring the enigmatic Standard Model, particle physics is a journey into the heart of matter.

The Building Blocks of the Universe

At its core, particle physics explains the building blocks of matter, delving into the smallest particles known to science. These particles, such as quarks and electrons, form the foundation of everything we see. The paradox of particle physics lies in its simplicity: the closer we look, the simpler the universe appears. This simplicity raises questions about the fundamental nature of reality, questions that researchers at institutions like the Max Planck Society are eager to explore.

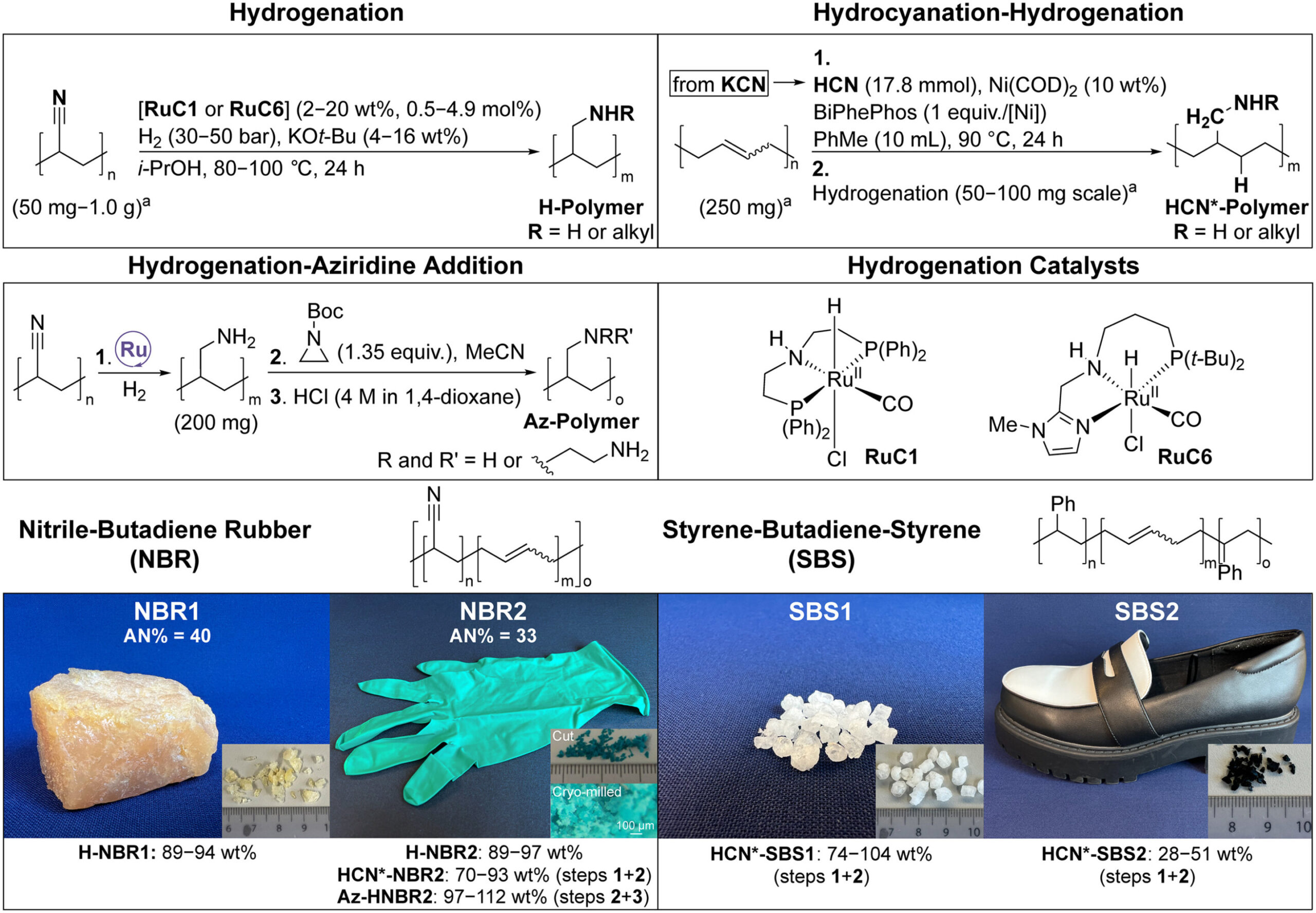

The Standard Model of particle physics is a cornerstone of this exploration. It describes the fundamental particles and forces that make up the universe, including the Higgs boson, which is responsible for giving mass to matter. Yet, despite its success, the Standard Model leaves many questions unanswered, suggesting the existence of physics beyond its current framework.

Simulating the Big Bang

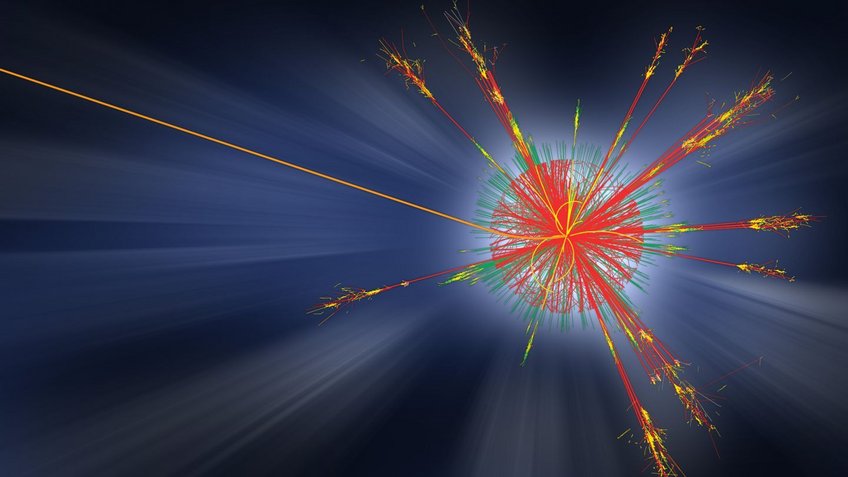

To understand the universe’s origins, physicists use particle accelerators to recreate conditions similar to those shortly after the Big Bang. These accelerators, like CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), propel protons to near-light speeds and collide them to study the resulting particle interactions. This process allows scientists to glimpse the universe as it was 13.8 billion years ago, offering insights into its evolution.

By analyzing the fragments from these high-energy collisions, researchers can explore the formation of matter and the fundamental forces at play. The LHC, with its 27-kilometer circumference, accelerates protons to energies of 14 teraelectron volts (TeV), creating conditions that existed less than a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang.

The Fundamental Forces

The universe is governed by four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces. While gravity is described by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, the other three forces are covered by the Standard Model. Unifying these theories remains a significant challenge in physics.

Electromagnetism influences charged particles, determining atomic and molecular structures. The strong nuclear force binds quarks within protons and neutrons, while the weak nuclear force is responsible for processes like radioactive decay. These forces operate through exchange particles known as bosons, with the Higgs boson playing a unique role by interacting with the Higgs field to give particles mass.

Beyond the Standard Model

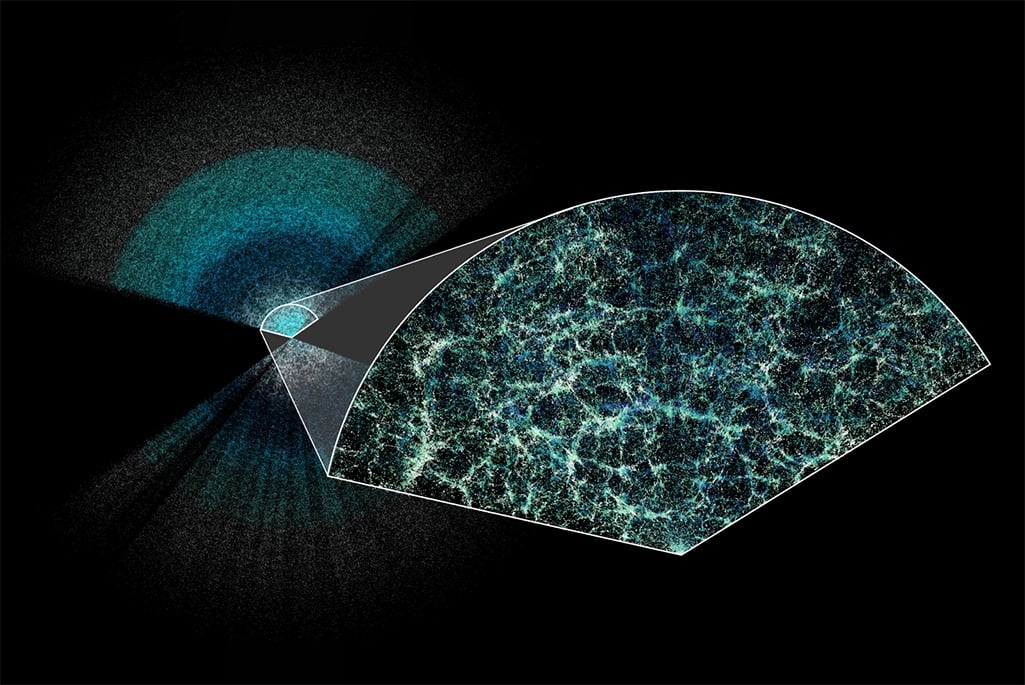

Despite its success, the Standard Model only accounts for about five percent of the universe, leaving dark matter and dark energy as mysteries. Theories beyond the Standard Model aim to address these gaps, exploring concepts like supersymmetry and string theory. Black holes, which connect large and small scales, may hold the key to unifying gravity with quantum mechanics.

One of the most intriguing questions is the matter-antimatter asymmetry observed in the universe. Shortly after the Big Bang, matter and antimatter existed in nearly equal quantities, yet a slight excess of matter led to the universe we know today. Understanding why this asymmetry occurred remains a central challenge for physicists.

The Future of Particle Physics

Looking ahead, the Future Circular Collider (FCC) is proposed as a successor to the LHC, aiming to reach collision energies of 100 TeV. This advancement would allow scientists to probe even closer to the Big Bang, potentially unlocking new insights into the universe’s early moments.

According to Marumi Kado, director at the Max Planck Institute for Physics, particles are merely excitations of more fundamental fields. The Higgs boson, for example, is an excitation of the Higgs field, which permeates the universe. Kado likens this to water droplets splashing from a lake’s surface, representing the visible manifestations of underlying fields.

As particle physics continues to push the boundaries of human knowledge, it not only deepens our understanding of the universe but also inspires new questions about the nature of reality itself. The journey into the subatomic world is far from over, promising discoveries that could reshape our comprehension of existence.