When scientists first sent microscopic worms into orbit in 2018, they sought to answer a pivotal question that has shaped discussions about long-duration space missions: What truly happens to the human body when gravity no longer exerts its pull on muscles and bones?

While changes in eyesight and bone density often make headlines, the most rapid and concerning transformations occur in the muscles. During a six-month stint on the International Space Station, an astronaut can lose nearly 40% of their muscle strength—a decline akin to several decades of aging. This deterioration not only hampers performance but also elevates the risk of injury, posing significant moral and practical challenges for future missions to Mars.

Insights from the First Worm Mission

To delve into the biological underpinnings of muscle decline, researchers turned to an unexpected ally: Caenorhabditis elegans, a roundworm no longer than a grain of sand. Despite its diminutive size, the worm’s cellular functions closely resemble those of human muscle. These worms utilize and store energy similarly to humans and exhibit muscle changes in space that mirror those observed in astronauts. Their small size and rapid life cycle make them ideal for space travel, where space is limited and experiments must proceed swiftly.

The 2018 Molecular Muscle Experiment, a project spearheaded by the United Kingdom, dispatched thousands of these worms to orbit. Upon their return to Earth, scientists discovered that the worms exhibited clear signs of muscle decline. Genes that typically support movement and maintain the stability of muscle cells’ internal structures were deactivated in microgravity. Additionally, genes associated with energy production, particularly those linked to the mitochondria, were subdued, indicating a sluggish metabolism.

The worms’ descendants, when grown in microgravity, demonstrated reduced force in their movements, corroborating the initial molecular findings.

Despite these changes, the worms grew and reproduced normally on the station, providing scientists with several generations to observe and proving that the experimental hardware functioned effectively in orbit. The findings illuminated why astronauts lose strength so rapidly and informed new strategies to safeguard crews on future deep-space missions.

A New Tool for a New Mission

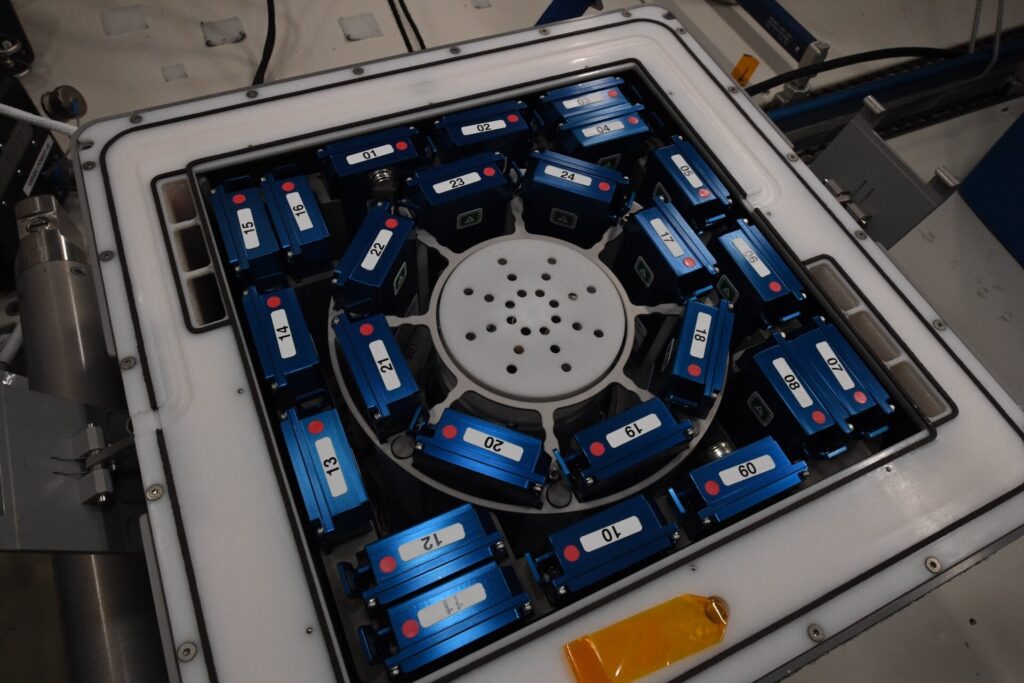

Building on these insights, a new project is underway. Teams from the University of Exeter and the University of Leicester are preparing for a new space mission featuring the Fluorescent Deep Space Petri Pod—a compact laboratory about the size of a loaf of bread. Engineered at Space Park Leicester, this three-kilogram device houses twelve small pods, each equipped with food, air, and temperature control. Four of the pods can be imaged in real-time, allowing researchers to observe living organisms’ responses to harsh space conditions.

The device enables scientists to study how living organisms react to vacuum, radiation, and weightlessness. Professor Mark Sims of Leicester, who played a crucial role in the engineering efforts, stated that the device reflects decades of experience with orbital experiments and positions the United Kingdom as a leader in life sciences research for upcoming missions near Earth and in deep space.

The first flight-ready units have successfully passed tests in the United States. Scheduled for launch in April 2026, the pods will initially operate inside the International Space Station before being moved outside to face open space. The worms, whose heads naturally emit a faint glow, will be monitored using miniature cameras. Images and sensor readings will be stored within the device and transmitted back through the station’s communication network. Eight pods will carry additional microbes or test materials to compare how different samples respond.

“Performing biology research in space comes with many challenges but is vital to humans safely living in space,” said Professor Tim Etheridge of the University of Exeter, who leads the scientific aspect of the mission.

He emphasized that the system opens new avenues for experiments on various launch vehicles, rather than relying solely on large missions.

What Researchers Hope to Discover

Exploring the reasons behind muscle weakening in orbit could reshape our understanding of aging, athletic training, and disease on Earth. Although worms may not seem similar to humans, their muscle cells function similarly at the molecular level. Their rapid growth allows scientists to observe multiple generations in a short period, making them a powerful tool for studying muscle decline.

Dr. Amanda Collis of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council highlighted the work as a prime example of international collaboration. She noted that it could pave the way for new treatments for muscular dystrophy and improve care for conditions like diabetes that affect metabolism and muscle health. These findings are also crucial for future astronauts who may spend extended periods far from home. Without effective measures to preserve muscle strength, even simple tasks could become perilous.

For Gaffney, who was captivated by space science from a young age, witnessing the United Kingdom’s first significant muscle research mission reach the International Space Station was a personal milestone. He believes each study contributes another piece to the broader understanding of how the human body adapts to life beyond Earth.

Practical Implications of the Research

Muscle decline in space tells a deeper story about the human body’s reliance on gravity. When that force is absent, cellular functions change, and tissues respond in ways that scientists are still unraveling. The worms in these experiments help uncover the earliest signs of these changes, bringing the field closer to solutions that could protect crews on long missions and aid people on Earth dealing with muscle loss due to aging or disease.

The findings from these worm studies may lead to improved methods for maintaining muscle strength during long space missions, shaping the safety of future flights to the Moon and Mars. The research could also inform the development of new therapies for muscle wasting caused by aging, metabolic illnesses, and diseases such as muscular dystrophy. By clarifying how muscle cells react to stress and reduced gravity, scientists gain insights that could enhance treatment, rehabilitation, and health outcomes for people on Earth.

Related Stories:

- ‘Light propulsion’ – scientists plan to launch tiny lifeforms into interstellar space

- Flatworms defy stem cell rules, offering a blueprint for human regeneration

- Scientists discover giant predatory worms dating back 518 million years

Like these kinds of feel-good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.