Human activities have significantly increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations, leading to ocean acidification at a rate unprecedented in at least 66 million years. Approximately a quarter of this CO2 is absorbed by the world’s oceans, resulting in lower pH levels and a decrease in the saturation state of aragonite (ΩAr). These changes pose a threat to marine ecosystems, particularly coral reefs, which are built by organisms with calcium carbonate skeletons.

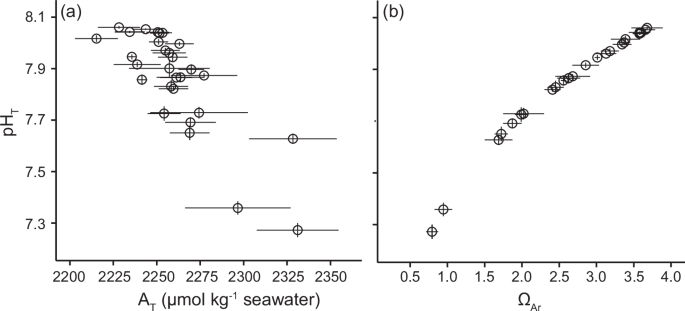

A recent study conducted at volcanic CO2 seep sites in Papua New Guinea has provided new insights into how coral reef communities are responding to these changes. Researchers examined 37 stations with varying levels of CO2 exposure, allowing them to observe the effects of ocean acidification on coral reef benthos under natural conditions.

Impact on Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are especially vulnerable to ocean acidification due to their reliance on calcium carbonate for structure. The study found that as ΩAr decreases, the cover of calcareous taxa such as scleractinian corals and crustose coralline algae (CCA) declines, while non-calcareous organisms like certain algae and sponges increase. This shift results in less diverse and structurally complex reef communities.

According to the study,

“The percent cover of all scleractinian corals combined did not change along the ΩAr gradient and averaged 36.15 ± 1.59% across all stations.”

However, without the massive Porites species, which were unaffected by ΩAr, the cover of other hard corals declined significantly.

Biological Responses and Thresholds

Most studies on ocean acidification have been conducted in controlled laboratory settings, which may not accurately reflect natural conditions. This study’s in situ approach revealed that biological responses to ocean acidification can be gradual or abrupt, depending on the taxa and environmental thresholds.

The research highlighted that

“High-CO2 communities are increasingly less diverse and less structurally complex.”

The study’s findings suggest that changes in reef communities are already occurring at current CO2 levels, with more drastic shifts expected by the end of the century.

Coral Diversity and Juvenile Densities

The study also found that hard coral diversity and juvenile densities declined along the ΩAr gradient. Adult and juvenile hard coral diversity were highly correlated, with significant reductions observed as ΩAr declined by as little as 0.3 units. Soft coral juveniles were particularly sensitive, disappearing at ΩAr values below 2.6.

Implications for the Future

The implications of these findings are profound. As atmospheric CO2 levels continue to rise, coral reefs will face increasing pressure. The study’s results indicate that

“By 2100, coral reefs could see considerable declines in hard coral diversity (40%), the percent cover of CCA (70%), and complex coral species (60%).”

These changes will depend heavily on the CO2 emissions pathway realized.

Experts emphasize the need for urgent action to reduce CO2 emissions to prevent further degradation of coral reefs. The study underscores the importance of in situ research to validate and predict the impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical need for continued research and conservation efforts to protect coral reefs. As ocean acidification progresses, understanding its effects on marine communities will be essential for developing strategies to mitigate its impact. The findings serve as a stark reminder of the interconnectedness of human activities and the health of our oceans.