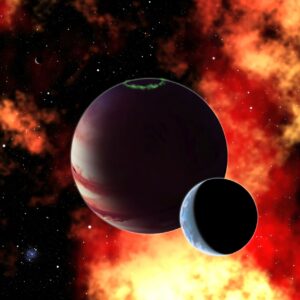

In a groundbreaking study, researchers have cast doubt on the existence of exomoons around planets in the habitable zones of red dwarf stars. Despite the absence of confirmed exomoons—moons orbiting exoplanets in other solar systems—the new simulations suggest that such moons are unlikely to thrive in these environments. This revelation, published in an upcoming issue of The Astronomical Journal, could reshape our understanding of where life-supporting conditions might exist beyond Earth.

The study, led by Shaan Patel from the University of Texas at Arlington, explores the dynamics of moons orbiting planets in the habitable zones of M-dwarfs, or red dwarfs—the most common type of star in the Milky Way. These stars are known to host rocky exoplanets, but their small size and dimness mean their habitable zones are much closer than those of brighter stars like our Sun. This proximity often results in tidal locking of the planets, posing challenges for the stability of any potential moons.

Understanding the Role of Exomoons

Moons play a crucial role in the habitability of planets. Earth’s moon, for instance, is instrumental in stabilizing our planet’s axial tilt, which helps maintain a climate conducive to life. It also influences ocean tides, fostering rich biodiversity in coastal regions. The potential for similar moons to exist around other planets raises intriguing questions about their role in creating life-supporting conditions elsewhere in the universe.

However, the new research titled “Tidally Torn: Why the Most Common Stars May Lack Large, Habitable-Zone Moons” suggests that the conditions necessary for such moons to exist around red dwarfs are rare. The study utilized N-body simulations to analyze the stability and lifetime of large, Luna-like moons in these systems, taking into account three-body interactions and tidal forces.

Simulations and Findings

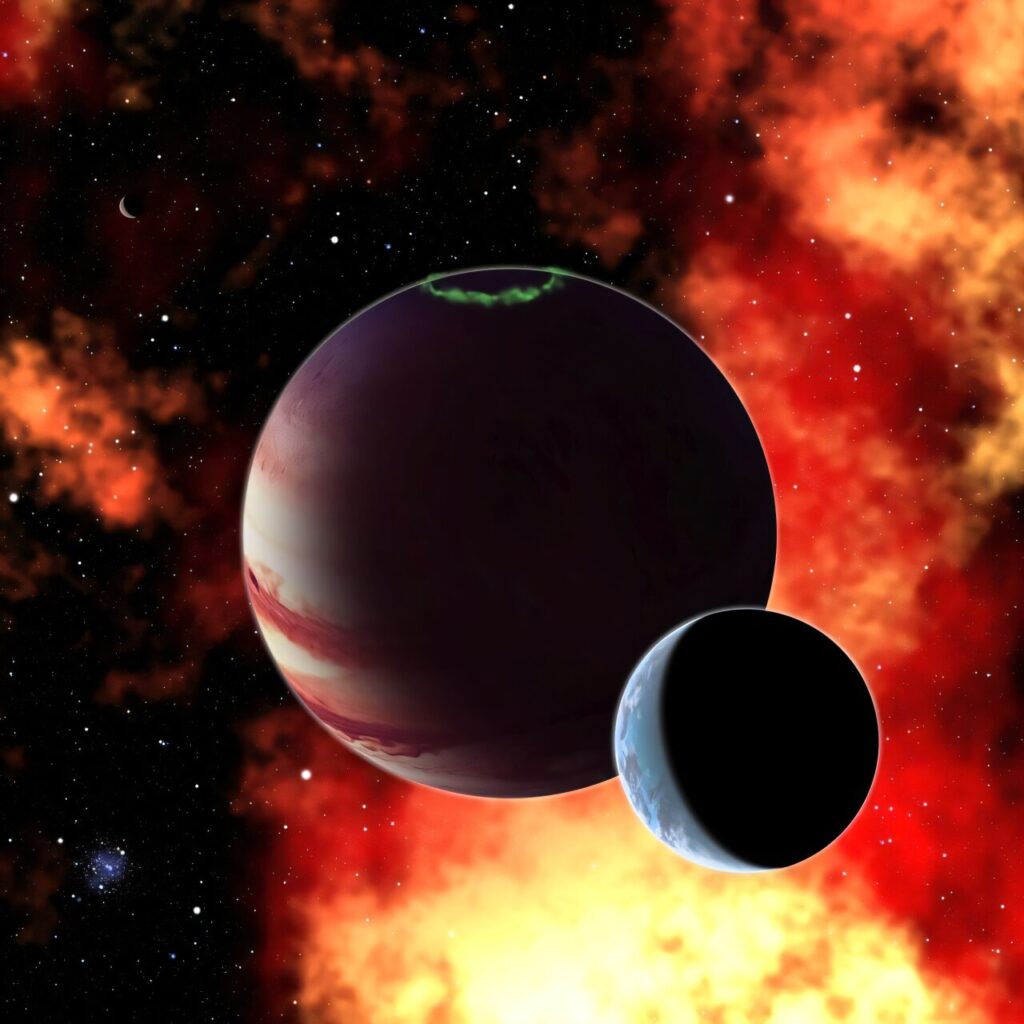

Through their simulations, the researchers varied the host planet’s mass and semi-major axis to determine the point at which exomoons become unstable. The key factor is the host planet’s Hill sphere, which describes its gravitational hold on the moon. The findings indicate that the larger the Hill sphere, the longer a moon can remain in orbit before escaping.

“Our findings suggest that HZ Earth-like planets in M-dwarf systems will lose large (Luna-like) moon(s) (if formed) within the first billion years of their existence,” the researchers explain.

The study further reveals that the type of M-dwarf significantly affects the outcome. There are ten classifications of M-dwarfs, from M0 to M9, each with varying temperatures that influence the location of the habitable zone and the strength of stellar tides. For example, simulations of star–planet–moon systems orbiting the habitable zone of M4-dwarfs show that the typical moon lifetime is less than 10 million years—an astoundingly short period compared to geological or astrophysical timescales.

Implications for Astrobiology

The implications of these findings are profound for the field of astrobiology. Previous research indicates that massive exomoons may experience extreme tidal heating, rendering them uninhabitable. This study adds to the narrative of fragility surrounding exomoons in M-dwarf systems.

“Together with our findings, this points to a general fragility of exomoons in M-dwarf systems,” the authors note.

Despite the general precariousness, there are scenarios where a large moon could survive for extended periods. For instance, if a large moon orbits a habitable Earth-mass planet around an M0-dwarf, it could last up to 1.35 billion years. This configuration weakens the stellar tide on the host planet, allowing the moon’s tide to play a more significant role.

Future Prospects for Exomoon Detection

The detection of exomoons could be revolutionized with the advent of new astronomical instruments. The proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory, with its primary mission to find Earth-like exoplanets, could also detect exomoons thanks to its large mirror. Similarly, the Giant Magellan Telescope, expected to begin observations in the 2030s, could directly image exoplanets and potentially identify exomoons.

While this study focused on M-dwarfs due to their prevalence and the number of rocky worlds they host, other types of stars with more distant habitable zones may offer better prospects for long-lived exomoons. These moons could play a role similar to Earth’s Luna, contributing to planetary habitability, or they might even be habitable themselves.

The search for exomoons continues, with the potential to unlock new dimensions in our understanding of life beyond Earth. As technology advances, the possibility of confirming these elusive celestial bodies becomes ever more promising.