The vision of a transformative rail network in Melbourne was first introduced to the public’s imagination when the City of Melbourne enlisted transport planner Graham Currie to evaluate the city’s transport network. This review included the consideration of a proposed road tunnel, the East West Link, and further developed the concept of a “north-south underground” rail tunnel, later known as the Metro Tunnel.

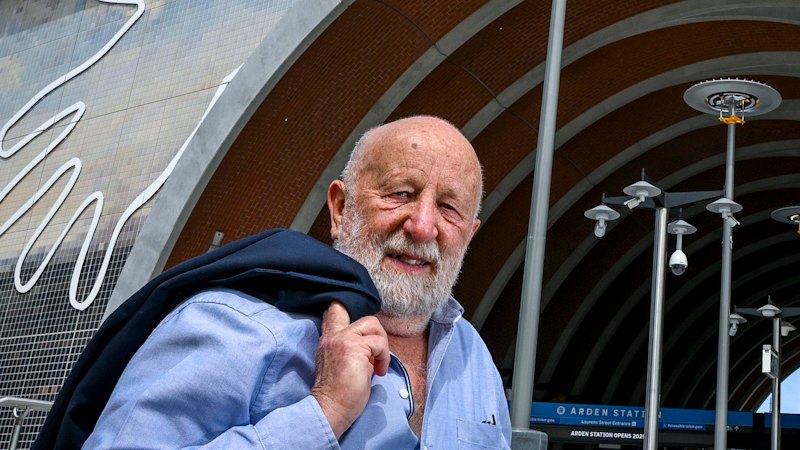

Currie’s report, influenced by his work on London’s Crossrail, which connected commuter rail corridors through a new tunnel under central London, called for similar innovation in Melbourne. “Frankly, at the time people thought I was a nutter,” Currie recalls. “We needed something game-changing.”

The Political Landscape and Growing Demand

By 2004, train usage in Melbourne had surged, with a 40% increase by 2008 and more than 60% by 2011. The existing network was overwhelmed, leading to chronic overcrowding and delays, which quickly escalated into a political crisis. Suddenly, the idea of an underground rail line became a priority.

In 2006, consultancy Sinclair Knight Merz (SKM) and McDougall were hired to scope and cost the north-south rail tunnel concept. The findings, obtained by The Age through a freedom of information request, revealed a favored route with stops at key locations like North Melbourne and Parkville. By 2007, enough groundwork had been laid for the project to be presented to the newly-appointed public transport minister, Lynne Kosky.

From Concept to Commitment

Despite growing interest, the Metro Tunnel remained a distant prospect until Sir Rod Eddington’s influential transport study in 2006. Commissioned to address congestion between Melbourne’s eastern and western suburbs, Eddington’s report ultimately recommended the construction of the Melbourne Metro, a 17-kilometer underground rail line linking the western suburbs to the southeast.

Eric Keys, a consultant involved in the Metro Tunnel project, recalls, “We felt extremely vindicated for probably what was then coming up to at least five, if not 10 years of working below the radar.”

In late 2008, the Victorian Transport Plan committed $38 billion to projects including the Metro Tunnel. However, securing funding was challenging until the global financial crisis prompted the federal government to seek “shovel-ready” projects, unlocking $4 billion for the Regional Rail Link and $40 million for detailed designs of the Metro Tunnel.

Challenges and Resurgence

The project faced setbacks when the Coalition halted it in 2010, but it was revived in 2014 when Labor regained power. Premier Daniel Andrews pledged to restart the original Metro Tunnel, aiming for a 2026 completion date. The project faced further challenges, including cost overruns and the COVID-19 pandemic, which increased the total cost to approximately $15 billion.

Tattersall, the project’s chief executive, highlighted the complexity of the project, noting, “Most projects would be four or five years late. We’re a couple billion dollars over budget, which sounds bad, but it’s not compared to what you see all over the world.”

Looking Ahead

As the Metro Tunnel prepares to operate with a limited timetable from Sunday, with full services commencing in February, the project’s impact remains to be seen. Current project director Ben Ryan is optimistic, citing the success of similar projects like London’s Crossrail and Sydney’s Metro, which have exceeded patronage expectations.

Kinnear, who retired in 2015, expresses concern about maintaining momentum for future projects, such as the proposed MM2. “We’ve still got a long way to go, but we’re certainly in a better position than we were 20 or 30 years ago,” he reflects.

The Metro Tunnel stands as a testament to the power of vision, persistence, and the complex interplay of politics and infrastructure development in shaping the future of urban transport.